Goethe, Kant and Intuitive Thinking

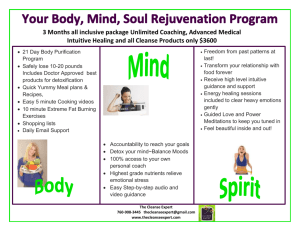

advertisement