An Evaluation of Buccal Infiltrations and Inferior Alveolar Nerve

advertisement

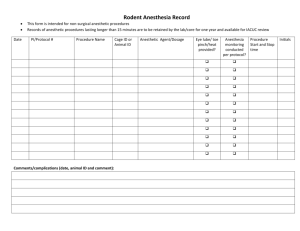

Clinical Research An Evaluation of Buccal Infiltrations and Inferior Alveolar Nerve Blocks in Pulpal Anesthesia for Mandibular First Molars Il-Young Jung, DDS, MSc, PhD, Jun-Hyung Kim, DDS, Eui-Seong Kim, DDS, MSc, PhD, Chan-Young Lee, DDS, MSc, PhD, and Seung Jong Lee, DDS, MSc, PhD Abstract We compared the anesthetic efficacy of inferior alveolar nerve blocks (IANBs) with that of buccal infiltrations (BIs) in mandibular first molars. Using a crossover design, all subjects received a standard IANB or a BI of 1.7 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline (Septanest; Septodont, Saint-Maru-des-Fosses, France) on two appointments separated by at least 1 week. Pulpal anesthesia was determined by using an electric pulp tester. Electric pulp testing was repeated at 5, 8, 11, 15, 20, 25, and 30 minutes after the injections. Anesthesia was considered successful if the subject did not respond to the maximum output of the pulp tester at two or more consecutive time points. Fifty-four percent of the BI and 43% of the IANB were successful; the difference was not significant (p ⫽ 0.34). The onset of pulpal anesthesia was significantly faster with BI (p ⫽ 0.03). In conclusion, BI with 4% articaine for mandibular first molars can be a useful alternative for clinicians because compared with IANB it has a faster onset and a similar success rate. (J Endod 2008;34:11–13) A Key Words This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dental College, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject. Thirty-five volunteers (23 men and 12 women) between 22 and 32 years of age were enrolled in this study. All subjects were in good health and were not taking any medication that would alter pain perception. The test teeth chosen for the experiment were mandibular first molars. Clinical examinations indicated that all the teeth were free of caries, large restorations, and periodontal disease and that none had a history of trauma or sensitivity. Using a crossover design, all subjects received a standard IANB (10) or a BI of 1.7 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline (Septanest; Septodont, Saint-Maru-desFosses, France) on two appointments at least 1 week apart. The injection point in BI was the mucobuccal fold adjacent to the mandibular first molar. All anesthetic injections were administered by a single operator who was not involved in assessing the outcome, and the order of the injection was randomized. The injections were administered with a 27-G needle attached to a standard aspirating syringe, and the anesthetic solution was deposited at a rate of 1.7 mL per 60 seconds. Pulpal anesthesia was determined by using an electric pulp tester (Gentle-Pulse vitality tester; Parkell Inc, Farmingdale, NY). Toothpaste was applied to the probe tip of a pulp tester, and the tip was placed in the occlusal third of the buccal area of the tooth. The power was increased slowly by turning the output control knob until the patient became aware of the stimulus. The rate of increase was adjusted manually, and it took 20 seconds from 0 to 10 (max). To establish the baseline reading, the testing was also performed before the injection. After the injection, a rubber dam was placed to facilitate pulpal testing, which was then repeated at 5, 8, 11, 15, 20, 25, and 30 minutes. The anesthesia was considered successful if the subject did not respond to the maximum output of the pulp tester at two or more consecutive time points. In addition to the Articaine, inferior alveolar nerve block, local anesthesia, mandibular first molar, pulpal anesthesia From the Department of Conservative Dentistry, Oral Science Research Center, College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. Supported in part by the Yonsei University Research Fund of 2006. Address requests for reprints to Dr Seung Jong Lee, Department of Conservative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, Yonsei University, Sinchon-dong, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 120-752. E-mail address: sjlee@yuhs.ac. 0099-2399/$0 - see front matter Copyright © 2008 by the American Association of Endodontists. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2007.09.006 JOE — Volume 34, Number 1, January 2008 lthough the inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) is the local anesthesia technique of choice when treating mandibular molars, not all IANB injections result in successful pulpal anesthesia (1–3). Therefore, many studies have sought to improve the success rate of IANB or to identify alternative methods of anesthesia (4 –7). Buccal infiltration (BI) is usually avoided in the mandibular molar regions because the presence of dense cortical bone impedes adequate diffusion of the anesthetic solution. Recently, Kanaa et al. (8) reported that mandibular BI is more effective with 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine than with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine. That study reported a 64.5% success rate for BI with 4% articaine in the lower first molar. In a separate investigation, Kanaa et al. (9) evaluated the anesthetic efficacy of IANB with 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine; the percentage of subjects reporting no pulp sensation on maximal stimulation in the first molar did not exceed 60% at any time period. Although it is inappropriate to compare the results of two independent investigations directly, these results show that BI can be as effective as IANB in anesthetizing the pulp of mandibular first molars. However, neither study compared the effectiveness of the two methods directly. This study compared the pulpal anesthetic efficacy of IANB with that of BI using 4% articaine in the mandibular first molars of adult volunteers. Materials and Methods Pulpal Anesthesia for Mandibular First Molars 11 Clinical Research TABLE 1. Mean Onset Time of Pulpal Anesthesia and Percentage (%) of Anesthetic Success for the Volunteer’s Mandibular First Molars Mean onset time (min) Anesthetic success† (%) BI IANB p Value 6.6 ⫾ 2.9 54 9.7 ⫾ 6.3 43 0.03* 0.34 *Significantly different at p ⬍ 0.05. †Anesthetic success: no response to the maximum output of the pulp tester on two or more consecutive time points. objective assessments of pulp anesthesia, each subject was also asked whether his/her lip was numb. Comparisons between IANB and BI for anesthetic success and the incidence of pulpal anesthesia at specific time points were analyzed by using a chi-square test. The onset of pulpal anesthesia was compared with a Wilcoxon rank sum test. All statistical analyses were performed on a personal computer using SPSS 12.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Results All volunteers reported lip numbness after the BI, whereas four subjects (11%) did not report significant lip numbness after the IANB. These four subjects reported pulpal sensation on electric stimulation at all time intervals. The onset time of pulpal anesthesia ranged from 5 to 15 minutes except in one subject who reported sensation on the electric pulp test until 30 minutes after IANB. However, the anesthesia was determined to be successful because the subject did not respond to pulp testing at 30 and 35 minutes. Five minutes was the most frequent onset time after BI, whereas 8 minutes was most common after IANB. The mean onset time of pulpal anesthesia (excluding failures) is shown in Table 1. The onset of pulpal anesthesia was significantly faster with BI (p ⫽ 0.03). Figure 1 shows the incidence of pulpal anesthesia at each time interval after BI and IANB. During the trial period, the differences were significant at 5 (p ⬍ 0.0001) and 8 minutes (p ⫽ 0.01). Anesthetic success occurred in 54% after the BI compared with 43% after the IANB (Table 1). However, this difference was not significant (p ⫽ 0.34). Discussion Although controlled comparisons of IANB (3, 6) have failed to show any difference between articaine and lidocaine solutions, two recent investigations (8, 11) found that articaine was significantly better than lidocaine in producing pulpal anesthesia in the mandibular first molars after BI. Therefore, we evaluated pulpal anesthesia using articaine for mandibular permanent first molar teeth. Although the anesthetic success rate of BI in this study was lower than the previous reports (8, 11, 12), we found that BI with 4% articaine was as effective as IANB in anesthetizing the pulp of the mandibular first molars. We are not sure why the success rates of articaine with BI and IANB were similar. A possible mechanism of the articaine is that it has better bone-penetration efficacy. Articaine contains a thiophene ring instead of a benzene ring found in lidocaine (13), which may allow the molecule to diffuse more readily. This speculation is corroborated by the claims that articaine is able to diffuse through soft and hard tissues more reliably than other local anesthetics and that maxillary buccal infiltration of articaine provides even a palatal soft-tissue anesthesia (14). An IANB is not only more painful than BI (15, 16) but also has a greater incidence of complications, such as trismus and hematoma (17). Considering these disadvantages of IANB and our results, BI can be a useful alternative to IANB in achieving pulpal anesthesia of a mandibular first molar. It is difficult to explain the lower success rate in this study, but it might be a race-specific effect. Kim et al. (18) observed 32 Korean adult cadavers and found that there were four communication patterns between the mandibular nerve branches in 12 cases (37.5%). They sug- Figure 1. Percentage of subjects reporting no sensation on maximum stimulation in first molars at the time intervals after buccal infiltration and inferior alveolar nerve block. 12 Jung et al. JOE — Volume 34, Number 1, January 2008 Clinical Research gested that some of these connections were a possible cause of incomplete anesthesia during dental practice. During the trial, four subjects did not experience profound lip numbness after IANB. Because pulpal anesthesia was not observed at any time interval in these patients, a lack of lip numbness seems to be a useful indicator in determining the failure of pulpal anesthesia. The onset time and duration of anesthesia are important considerations when clinicians choose an anesthetic method. Subjects with anesthetic failure were excluded from the analysis of the onset times in this study. Pulpal anesthesia occurred in less than 8 minutes in 84% of the BI and 67% of the IANB cases, and the difference was significant. Although our research protocol was not sensitive enough to measure the onset time accurately, it would be possible to draw a conclusion from this result that BI is better when a faster onset is required. Although the trial period was not long enough to evaluate the duration of anesthesia, it appeared that pulpal anesthesia with BI injections began to decline after 20 minutes, whereas it remained constant for 30 minutes with IANB injections. Therefore, BI injections may not be appropriate for procedures that take longer than 20 minutes. However, if additional intrapulpal injections are performed, the pulp can be removed without difficulty in an emergency endodontic treatment on a first molar. There are some limitations to this study. Although all of the investigators assessing pulpal anesthesia were blinded to the injection procedure, this study was not designed as a double-blind trial. Because most of the volunteers were graduate or undergraduate students at a dental college and had clinical experience, it was not possible to blind all of the subjects to the treatments given at any particular visit. Therefore, the results might be subject to a response bias. Another limitation concerns the presence of normal pulp in the subjects participating in this study. Local anesthetics are generally much less effective when administered to patients with inflamed tissue. Hargreaves et al. (19) suggested that the rate of failure of local anesthetic injections in patients with irreversible pulpitis was eight times higher than in normal control subjects. Therefore, it is unclear whether the same result would be achieved in patients with irreversible pulpitis. However, no controlled clinical study has shown the superiority of one technique over the other in patients with irreversible pulpitis. In conclusion, BI with 4% articaine for mandibular first molars can be a useful alternative for clinicians because compared with IANB it has a faster onset and a similar success rate. JOE — Volume 34, Number 1, January 2008 References 1. Cohen HP, Cha BY, Spangberg LS. Endodontic anesthesia in mandibular molars: a clinical study. J Endod 1993;19:370 –3. 2. Kennedy S, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Weaver J. The significance of needle deflection in success of the inferior alveolar nerve block in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod 2003;29:630 –3. 3. Claffey E, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Weaver J. Anesthetic efficacy of articaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod 2004;30:568 –71. 4. Clark S, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ. Anesthetic efficacy of the mylohyoid nerve block and combination inferior alveolar nerve block/mylohyoid nerve block. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;87:557– 63. 5. Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck FM. Anesthetic efficacy of different volumes of lidocaine with epinephrine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Gen Dent 2002;50:372–5. 6. Mikesell P, Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. A comparison of articaine and lidocaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Endod 2005;31:265–70. 7. Ianiro SR, Jeansonne BG, McNeal SF, Eleazer PD. The effect of preoperative acetaminophen or a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on the success of inferior alveolar nerve block for teeth with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod 2007;33:11– 4. 8. Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG. Articaine and lidocaine mandibular buccal infiltration anesthesia: a prospective randomized double-blind crossover study. J Endod 2006;32:296 – 8. 9. Kanaa MD, Meechan JG, Corbett IP, Whitworth JM. Speed of injection influences efficacy of inferior alveolar nerve blocks: a double-blind randomized controlled trial in volunteers. J Endod 2006;32:919 –23. 10. Dionne RA, Phero JC, Becker DE. Management of pain and anxiety in the dental office. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002. 11. Robertson D, Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck M, McCartney M. The anesthetic efficacy of articaine in buccal infiltration of mandibular posterior teeth. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138:1104 –12. 12. Haas DA, Harper DG, Saso MA, Young ER. Lack of differential effect by Ultracaine (articaine) and Citanest (prilocaine) in infiltration anaesthesia. J Can Dent Assoc 1991;57:217–23. 13. Isen DA. Articaine: pharmacology and clinical use of a recently approved local anesthetic. Dent Today 2000;19:72–7. 14. Clinicians guide to dental products and techniques: Septocaine. CRA Newsletter, Provo, UT, June 2001. 15. Kaufman E, Epstein JB, Naveh E, Gorsky M, Gross A, Cohen G. A survey of pain, pressure, and discomfort induced by commonly used oral local anesthesia injections. Anesth Prog 2005;52:122–7. 16. Sharaf AA. Evaluation of mandibular infiltration versus block anesthesia in pediatric dentistry. ASDC J Dent Child 1997;64:276 – 81. 17. Malamed SF. Handbook of local anesthesia, 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby, 2004. 18. Kim SY, Hu KS, Chung IH, Lee EW, Kim HJ. Topographic anatomy of the lingual nerve and variations in communication pattern of the mandibular nerve branches. Surg Radiol Anat 2004;26:128 –35. 19. Hargreaves KM, Keiser K. Local anesthetic failure in endodontics: mechanisms and management. Endod Topics 2002;1:26 –39. Pulpal Anesthesia for Mandibular First Molars 13