I'll Keep You in Mind: The Intimacy Function of Autobiographical

advertisement

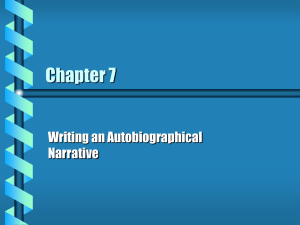

APPLIED COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) Published online 18 December 2006 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/acp.1316 I’ll Keep You in Mind: The Intimacy Function of Autobiographical Memory NICOLE ALEA1* and SUSAN BLUCK2 1 University of North Carolina Wilmington, USA 2 University of Florida, USA SUMMARY An experimental study examined whether autobiographical memory serves the function of maintaining intimacy in romantic relationships. Young and older adults (N ¼ 129) recalled either autobiographical relationship events or fictional relationship vignettes. Intimacy (warmth, closeness) was measured before and after remembering. Warmth was enhanced after recalling autobiographical events irrespective of individuals’ age and gender; women also experienced gains in closeness. The role of memory characteristics (quality and content) in producing changes in intimacy was also examined. Personal significance of the autobiographical memory was the best predictor of warmth and closeness in the relationship, though how frequently the memory was thought or talked about, and how intimate the memory was also predicted levels of closeness, particularly for women. Results are discussed in terms of how autobiographical memories can be used to foster intimacy in romantic relationships across adulthood. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Nurturing intimacy in relationships is a fundamental human motivation (e.g. Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Speculation exists about mechanisms that promote intimacy in relationships across adulthood; most notable are socio-emotional motivations (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999) and interpersonal processes (Reis & Shaver, 1988). Memory mechanisms, however, have received comparatively little attention (c.f., Holmberg, Orbuch, & Veroff, 2004; Karney & Coombs, 2000; Pasupathi, 2001). Yet, personal autobiographical memories of life experiences, such as remembering the day one met their spouse (Belove, 1980), may serve the function of keeping loved-ones in mind, and in turn, close in one’s heart. The current study is the first to use an experimental method to investigate the intimacy function of autobiographical memory (Alea & Bluck, 2003). The first aim of the study is to examine whether self-reported intimacy in romantic relationships is enhanced after remembering autobiographical relationship events, taking potential age and gender differences into account. The second aim is to examine whether autobiographical memory characteristics (i.e. quality and content) influence the extent to which the intimacy function is served. *Correspondence to: Nicole Alea, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina Wilmington, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, NC 28403-5612, USA. E-mail: alean@uncw.edu Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1092 N. Alea and S. Bluck A FUNCTIONAL APPROACH TO AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MEMORY: THE INTIMACY FUNCTION The idea that autobiographical memory is used to enhance intimacy is rooted in the ecological approach (Neisser, 1978) that emphasizes not only how well humans remember the events of their life, but also why they remember. That is, what function does autobiographical remembering serve (e.g. Bluck & Alea, 2002; Bruce, 1989)? The social function has been theorized to be the most fundamental because autobiographical memory may promote the social bonding necessary for species survival (Neisser, 1978; Nelson, 1993; Pillemer, 1998). The intimacy function is one of several theorized social functions. A growing number of studies substantiate the claim that remembering life events can foster intimacy (Bluck, Alea, Habermas & Rubin, 2005; Hyman & Faries, 1992; Pasupathi, Lucas, & Coombs, 2002). These studies, however, mostly use self-report assessments and examine the relative frequency of using autobiographical memory to serve an intimacy function as compared to serving various other social and non-social functions. The current study goes beyond a self-report methodology, using a pre-post control group design that moves closer to the way autobiographical remembering occurs in every day life. We examine whether remembering two autobiographical memories about one’s romantic partner results in immediate, measurable increases in felt intimacy towards one’s partner (i.e. the person who is being remembered). Does remembering someone (in their absence) keep them close? This is different than Webster’s (1995) intimacy function of reminiscing which is grounded in a psychodynamic reminiscence tradition, which primarily involves remembering loved ones who have passed away in order to keep them close. Autobiographical memory sharing may also serve an intimacy function (Alea & Bluck, 2003) in regards to the listener. People may feel closer to a conversational partner after sharing an autobiographical memory with them due to personal disclosure processes (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998). The current study, however, focuses on how remembering relationship events enhances feelings of intimacy toward the person being recalled (i.e. the person who is being remembered). Since participants first recalled a memory, and then spoke it to the researcher, remembering and sharing are confounded in the current study (as they often are in every day life). It is remembering the loved one, not speaking that memory out loud, which we argue is serving an intimacy function. The study has an experimental design, including a control condition in which half of the participants remembered fictional relationship vignettes. These vignettes mirror the structure, quality and content of autobiographical memories about relationship events (Dixon, Hultsch, & Hertzog, 1989), but are non-autobiographical. As such, fictional narratives are an appropriate control for examining whether autobiographical memories serve an intimacy function. Demonstration of an intimacy function is apparent if ratings of felt intimacy increase after participants remember autobiographical relationship events, but not after remembering fictional vignettes. The purpose of the current study was to experimentally demonstrate that such an effect exists, since such an effect has been widely theorized, and suggested through self-reports. THE REMEMBERER AND THE MEMORY The extent to which autobiographical remembering enhances intimacy in romantic relationships may depend both on who is remembering, and certain characteristics of the Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1093 memory. Alea and Bluck (2003) proposed a conceptual model outlining variables likely to play a role when individuals use autobiographical memory to serve social functions, such as fostering intimacy. Two variables discussed in the model are characteristics of the rememberer (e.g. age and gender) and characteristics of the memory (e.g. emotionally rich and vivid). The possible influence these variables have on the extent to which an intimacy function is served are reviewed in the following sections, along with related study hypotheses. Characteristics of the rememberer: age and gender Age Lifespan theories (e.g. Erikson, 1980; Neugarten, 1979) suggest that at both ends of adulthood, enhancing intimacy in relationships is a normative life-phase task. Tasks in young adulthood revolve around developing intimate relationships (Erikson, 1980) and late life goals involve sustaining a small number of highly meaningful relationships (Carstensen, 1993; Carstensen et al., 1999; Lang, 2001). In short, maintaining intimacy in relationships appears to be a normative life-phase task that guides the goals that both young and older adults have when reflecting on their personal past (Bluck & Habermas, 2001; Staudinger, 2001). Further, few or no age differences in memory quality are found when older adults remember personally significant events from their life (see Cohen, 1998 for a review). Normative age changes do appear in episodic memory (Zacks, Hasher, & Li, 2000) but do not always transfer to autobiographical events. Thus, we hypothesize that both young and older adults will experience gains in intimacy after remembering relationship events. The use of memory to enhance intimacy should show age continuity (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999). Gender Men are clearly interested in intimate relationships (e.g. Acitelli & Antonucci, 1994; Fehr, 2004), but women focus more attention on fostering interpersonal connections (e.g. see Reis, 1998 for a review). Emerging evidence shows that men and women tend to remember life events differently. When asked about how they use autobiographical memory in daily life, women report greater value in purposeful reminiscing (Pillemer, Wink, DiDonato, & Sanborn, 2003). Women’s autobiographical memories also tend to be more specific (Pillemer et al., 2003) and more emotional and vivid (Davis, 1999), particularly when remembering relationship events (Ross & Holmberg, 1992). Thus, although not all studies of autobiographical memory find gender differences (e.g. Rubin, Schulkind, & Rahhal, 1999), we expect that if gender differences are found, they would be in the direction outlined above. Women are expected to show greater increases in intimacy after autobiographical remembering than are men. Characteristics of the memory: quality and content Characteristics of a memory may also determine the extent to which its recall might enhance intimacy (Alea & Bluck, 2003). Recalling dropping your partner off at work last Thursday, for example, may not necessarily increase intimacy. Memories that have certain qualities (e.g. vividness; Pillemer, 1998) or have particular content (e.g. intimate relationship events) should be more likely to foster intimacy. No research has directly Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1094 N. Alea and S. Bluck examined the memory characteristics that lead to enhanced intimacy; some indirect evidence does exist. Quality Research on the quality of autobiographical memory has historically investigated the role that memory vividness and personal significance play in recall. Personally significant memories are often associated with better recall (see Winograd & Neisser, 1992 for a review). It is likely that the vividness and significance of a remembered event not only affects performance but also influences the extent to which autobiographical memory serves important functions. Emotional re-experiencing during recall may also be related to autobiographical memory serving an intimacy function. Feeling positive emotions during recall that were felt at the time of the event are likely to affect current mood (Fiedler, Nickel, Muehlfriedel, & Unkelbach, 2001). While remembering positive events is likely to have a positive effect on current mood, however, it is unclear whether the re-experiencing of positive emotions will also generalize to feelings and views about one’s current level of relationship intimacy. Thus, though overall increases in positive affect as a result of telling positive memories was expected, analyses concerning the relation of positive re-experiencing to increased intimacy after autobiographical remembering were exploratory. A final quality that has received attention for its role in influencing memory performance is rehearsal. Memories that are thought and talked about more often are sometimes remembered better (e.g. Anderson, Cohen, & Taylor, 2000; Bluck & Li, 2001; Bohannon, 1988), although, rehearsal can also lead to some habituation of the memory’s emotional effect (Sloan, Marx, & Epstein, 2005). Thus, it is unclear whether rehearsal should be expected to influence memory function. In sum, this study examines several classic qualities of memory and how they relate to autobiographical memory serving an intimacy function. The only clear hypothesis is that memories that are personally meaningful are more likely to foster intimacy in romantic relationships. Content The content of the remembered experience (e.g. McAdams, 1984; Woike, Gershkovich, Piorkowski, & Polo, 1999) may also be relevant to enhancing intimacy. Do particularly intimate events need to be remembered or can recalling generally positive events foster intimacy? Individuals sometimes spontaneously express themes of communion (e.g. love and caring–intimacy) in autobiographical narratives (McAdams, Hoffman, Mansfield, & Day, 1996). Do autobiographical memory narratives that include more communal themes foster greater intimacy? Memories that are rich in communal themes (i.e. more intimate memories) are expected to result in greater gains in intimacy. METHOD Design The study is a 2 (Age: young, old) 2 (Gender: men, women) 2 (Condition: autobiographical memory, fictional vignette) 2 (Time: pre, post) mixed design. Condition was a between-subjects factor to avoid non-symmetrical carry-over effects (Heiman, 2001). Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1095 Participants Participants were 129 young (n ¼ 32 men, 32 women; M ¼ 27.94 years; SD ¼ 4.84) and older adults (n ¼ 33 men, 32 women; M ¼ 74.66 years; SD ¼ 6.05). All participants were in long-term relationships, operationally defined as a marriage or cohabitation that had been ongoing for at least 2 years. The study focuses on intimacy in romantic relationships because of their salience across the adult lifespan (e.g. Carstensen, Graff, Levenson, & Gottman, 1995) and their potential impact on psychological well-being (e.g. Acitelli & Antonucci, 1994). Only one partner participated; there were no couples in the study. Older adults had been in their relationship longer (M ¼ 46.52 years; SD ¼ 13.33; 100% in marriages) than younger adults (M ¼ 5.44 years, SD ¼ 2.79; 67% in marriages), t (127) ¼ 24.64, p < 0.001. Participants reported being satisfied in their relationship on a measure of global relationship satisfaction (Norton, 1983), M ¼ 39.62 out of a possible 45, SD ¼ 6.50. Younger adults were recruited through graduate programmes and paid $10. Older adults were unpaid volunteers recruited through community organizations and screened for cognitive impairment (Roccaforte, Burke, Bayer, & Wengel, 1992). Recruitment materials did not mention long-term relationships or relationship memories in order to avoid initial sample biases. Age differences in cognitive functioning were typical (Schaie, 1994) with respect to vocabulary ability (Wechsler, 1981), reasoning ability (Thurstone, 1962), and episodic memory (Rey, 1941).1 Participants spoke fluent English. Seventy per cent of the younger adults and 97% of the older adults were Caucasian. Young adults had an average of 17.89 (SD ¼ 2.40) years of education, and older adults 16.42 years (SD ¼ 3.20), t(126) ¼ 2.94, p < 0.05. Young and older adults both reported (Maddox, 1962) being in good to very good health (young: M ¼ 1.83, SD ¼ 0.78; old: M ¼1.80, SD ¼ 0.88), t (127) ¼ 0.19, p > 0.05. Measures Intimacy measures Two reliable intimacy measures (e.g. Osgood, Suci, & Tennenbaum, 1957; Schaefer & Olson, 1981) sensitive to change (e.g. Hickmon, Protinsky, & Singh, 1997; Karney & Bradbury, 1997) and representative of distinct constructs, warmth and closeness, were employed. Directions encouraged participants to tap current feelings of intimacy. Warmth. A semantic differential scale (SMD, Osgood et al., 1957) was used to assess relationship warmth, which is the aspect of intimacy that is emotion-based (i.e. measures feelings about one’s relationship). Fifteen adjective-pairs are listed as oppositions (e.g. lonely–satisfied) and rated on a 7-point Likert-scale positioned between the adjective pair (Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.95 pre-memory and 0.97 post-memory). Closeness. Relationship closeness was assessed with 24 items from the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships questionnaire (PAIR, Schaefer & Olson, 1981) using a Likert-scale, ranging from 1 (very strong disagreement) to 5 (very strong agreement). Closeness is characterized by the interdependence of a couple, including how 1 Basic cognitive ability differences between young and older adults could potentially influence the extent to which intimacy is enhanced after autobiographical remembering (e.g. if memory is poor, the intimacy function of autobiographical memory may not be utilized). Major intimacy results do not change when cognitive ability assessments are used as covariates. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1096 N. Alea and S. Bluck they interact as a close unit and relate to one another (Mashek & Aron, 2004). Questions ask about the couple’s emotional, intellectual, social and recreational connectedness. The sexual intimacy subscale of the PAIR was not used in the current project. We report a single global PAIR score (Schaefer & Olson, 1981). The PAIR had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.90 at both times of measurement). The PAIR also has a Conventionality subscale, which assesses the extent to which individuals are presenting their relationship in socially desirable way. Participants fell below the cut-off for social desirability in responding (M ¼ 21.24, cut-off criterion ¼ 30; Schaefer & Olson, 1981). A paired-sample t-test also indicates that there was no significant increase on this scale from pre- to post-remembering (M ¼ 22.32) regardless of condition. This suggests that any demand characteristics (i.e. to portray one’s relationship in a positive light) were below criterion levels and the same across conditions. Memory characteristics Memory quality. Memory quality was assessed with 10-items from the Memory Quality Questionnaire (MQQ, adapted from Bluck, Levine, & Laulhere, 1999) completed for each of the two memories. Responses were made on 5-point Likert-scales. Mean scores were created for each item across the two autobiographical events remembered (n ¼ 65). Exploratory factor analysis (Promax rotation; see Alea, 2004 for details) resulted in three factors including positive re-experiencing, personal significance, and rehearsal. The positive re-experiencing factor (32% variance, Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.80), includes four items regarding basic positive and negative emotions at the time of recall (e.g. ‘Did this memory make you feel happy?’). The personal significance factor (25% variance, Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.85), includes four items regarding how memorable, important, emotional (with no regard to valence), and vivid the memory was (e.g. ‘How significant or important is this memory to you?’). The rehearsal factor (10% variance; Cronbach’s a ¼ 0.65), includes two questions about the frequency of thinking and talking about the past.2 Memory content. Memory narratives were coded for themes of communion (see McAdams, 2001 for coding scheme). Communal themes include love and friendship (‘how lucky we are that we found each other’), dialogue (‘we reflected back on our marriage’), caring and helping (‘I was watching to make sure that she was enjoying herself’), and unity and togetherness (‘it was just fun to get everybody together’). Communal themes were coded as either present or absent in the narrative. Two coders blind to study hypotheses were trained to reliability on a subset of narratives (n ¼ 48) blinded for participant gender. Percent agreement (with kappa in parentheses) were love and friendship ¼ 83% (0.65), dialogue ¼ 92% (0.80), caring and helping ¼ 98% (kappa not computed, there was a constant in the table of association), and unity and togetherness ¼ 92% (0.75). After reliability was obtained, one coder proceeded to code the remaining narratives and any questions were discussed. This coder’s scores were used in all analyses. A single communal theme score was created which ranged from 0 (absent) to 8. Participant’s scores were well below the scale median (M ¼ 2.70, SD ¼ 1.44). Individuals, in general, were not recalling highly communal memories. 2 It is recognized that the N is small for a factor analysis. Despite this, the 3-factor solution accounted for 67% of the variance (root mean square residual ¼ 0.04), using a > 0.50 factor loading criterion (Cliff & Hamburger, 1967; Kaiser, 1960). It is also recognized that factors with fewer than four loadings are usually not interpreted (Gorsuch, 1983), but the rehearsal index was of theoretical significance. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1097 Control variable Basic affect. Affect was measured with the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) before and after remembering. Responses were made on a 5-point Likert-scale (Cronbach’s a above 0.87 for both positive and negative affect, pre and post memory). Basic affect was measured for use as a traditional covariate, and concomitant variable (i.e. one that changes with the dependent variable; Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991). Procedure Interviewers were women in their early to mid 20s. Females were used to enhance the likelihood that participants would disclose personal information (Shaffer, Pegalis, & Bazzini, 1996). Debriefing questions suggest that interviewer age and gender did not influence recall or sharing of memories. Interviewers followed a structured script for the 90-minute session, and responded to participants’ memories with interested expressions but no verbal response. Attempts were made to represent a real life situation, where memories were shared with an engaged listener in a quiet, comfortable, home-like environment. Participants completed the background and health questionnaire, the PANAS, the intimacy measures, followed by the cognitive ability measures. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Regardless of condition, participants were asked to recall two positive event memories, a vacation and a romantic evening. The fictional vignettes have been used in both memory and narrative text research (e.g., Dixon et al., 1989; Ross & Holmberg, 1992). The order of recalling the two events was counterbalanced, and there were no order effects. Autobiographical memory condition Participants were given 2 minutes to think about one autobiographical event (e.g. a vacation). Specifically, they were instructed to, ‘think about a vacation that you had with your partner. During this time try to remember where you were, what you did, and what you were thinking and feeling. The story can be about something that happened years ago or more recently, as long as the memory is memorable and positive for you’. This timeframe was used to equate the memory conditions (the pre-recorded fictional vignettes took approximately 2 minutes to play). Then participants were asked to, ‘tell me everything you can remember about a positive (vacation) that you had with your partner. Tell me about where you were, what you did, and what you were thinking and feeling’. They recalled all that they could about the event. The participant’s memory was probed using standard probes until 10 minutes had expired. The entire procedure was then repeated for the second autobiographical event (e.g. romantic evening). Fictional vignette condition The vignettes were about a couple’s romantic evening, and vacation. These were an appropriate control because they are analogous to autobiographical narratives in many ways. The narratives are personal texts in colloquial style, describe a single event, involve information about characters’ intentions, evaluations, behaviours and ruminations, are moderately emotional stories that illicit positive feelings, and are interesting and true-to-life (Dixon et al., 1989). They also require the use of open-ended free recall, contain Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1098 N. Alea and S. Bluck narrative structure, and are about the same event. These vignettes were also appropriate because of their obvious difference; they are non-autobiographical. Thus, this condition provides a dimension on which the two memories should differ if autobiographical memory, and not memories that people do not ‘own’, serve an intimacy function. Participants listened for 2-minutes to one of the vignettes pre-recorded in a clear voice, and played via audiotape. Specifically, they were asked to ‘listen to a story about a vacation that a couple had together. During this time think about where they were, what they did, and what they were thinking and feeling. The story is about an event that is memorable and positive for the couple’. They were then asked to ‘tell me everything you can remember about the positive vacation that the couple had together. Tell me about where they were, what they did, and what they were thinking and feeling’. They were given 10-minutes to remember everything they could, followed by standard probes. The procedure was then repeated for the other vignette. Memory interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim (see Table 1 for examples).3 After remembering relationship events, participants were immediately given the warmth (SMD) and closeness (PAIR) measures answered previously, with questionnaire order counterbalanced across pre- and post-test, and with items on these questionnaires presented in a different order than at the initial assessment. Instructions emphasized current assessment of warmth and closeness in the relationship (regardless of initial levels). At least 30 minutes (i.e. cognitive ability measures, remembering relationship events) had elapsed since the first time the intimacy measures were completed. Participants were then administered the MQQ (memory quality) and PANAS (affect). Results The results are in two sections. The first uses analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to examine whether autobiographical memory fosters intimacy, and whether it varies by age and gender (Aim 1). The second section uses hierarchical regression analysis to examine whether particular autobiographical memory characteristics predict gains in intimacy (Aim 2). Correlations among study variables are reported in Table 2. Does memory serve an intimacy function? Does the rememberer affect intimacy gains? Analyses were conducted separately for warmth and closeness, examining whether intimacy increased after autobiographical remembering (i.e. the intimacy function), and if so, whether such increases vary by characteristics of the rememberer. There were no age, gender, or condition differences in intimacy at initial assessments. Initial intimacy (warmth or closeness) levels were covaried in analyses to control for individual differences in intimacy. As expected, preliminary analyses indicated increases in positive affect (but not negative affect) from pre- to post-autobiographical remembering. Thus, analyses are conducted without change in positive affect as a covariate, and then with change in positive affect as a covariate, to examine whether intimacy changes were concomitant with or independent of changes in positive affect. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 3. 3 We asked participants whether they thought of their own partner when recalling the fictional vignettes, 53% said ‘yes’. Despite this, analyses revealed that thought intrusions did not lead to enhanced intimacy after remembering fictional relationship vignettes. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1099 Table 1. Example of a remembered event (romantic evening) Autobiographical memory condition Fictional vignette condition ‘It was the first time we went to the Performing Arts Center together, which we’ve done several times since then. We went to see a dance recital . . . but we went to dinner ahead of time and had sushi: one of our favorites . . . It was in the winter time because we got to the Performing Arts Center early but it was dark already and we were just milling around outside waiting. It was a clear cool night, start out, and we were just walking around the outside and he started singing to me. Some very old-fashioned romantic song that he sings about putting your arm in mine as we walk, or something liked that. It was very very romantic . . . it was early in our relationship so I was very much impressed and definitely falling for him at that time. It made a big impression’. ‘Jim and Theresa were a couple who lived across the Potomac from Washington. It was the 4th of July and they were going to go to the mall to have an evening to celebrate their own relationship and also to celebrate the 4th of July, with the fireworks and the concert. Jim packed a picnic lunch . . . and off they went. They drove across the bridge and they arrived and it was terribly crowded so they parked up away from the mall and they presumably carried their basket with them to a spot . . . And I can just see them arranging a nice little area for themselves. And then there of course was the pleasure of the concert, followed by the fireworks over the Washington Monument and they enjoyed the whole evening so much. They were surrounded by friendly people and they decided that they would make this an annual celebration . . . Not only to honour the 4th of July but their own relationship’. A 2 (Condition: autobiographical memory, fictional vignette) 2 (Age: young, old) 2 (Gender: male, female) ANCOVA was conducted to examine post remembering levels of warmth in the relationship. The primary effect of interest, the Condition main effect, was significant, F(1, 119) ¼ 6.12, MSE ¼ 353.79, p < 0.05, h2p ¼ 0.05. Individuals in the autobiographical memory condition reported feeling more warmth in their relationship after remembering than those recalling vignettes (see Figure 1). There was no age or gender main effect, nor any interactions. The ANCOVA was conducted again including concomitant pre-post change in positive affect as a covariate. The Condition main effect became marginally significant, F(1, 118) ¼ 3.77, MSE ¼ 209.48, p ¼ 0.06, h2p ¼ 0.03. This likely occurred because warmth in the relationship after autobiographical remembering and change in positive affect from pre- to post-remembering share variance (r ¼ 0.21). An age effect also emerged, F(1, 118) ¼ 5.43, MSE ¼ 302.44, p < 0.05, h2p ¼ 0.04. Older adults reported more warmth in their relationship overall (M ¼ 93.04, SD ¼ 18.17) than younger adults (M ¼ 89.92, SD ¼ 12.94). A 2 (Condition: autobiographical memory, fictional vignette) 2 (Age: young, old) 2 (Gender: male, female) ANCOVA was conducted to examine levels of closeness after remembering. The Condition main effect was not significant, F(1, 119) ¼ 2.08, MSE ¼ 65.39, p > 0.05, and there was no main effect for age or gender. There was, however, a Condition Gender interaction, F(1, 119) ¼ 3.83, MSE ¼ 120.07, p ¼ 0.05, h2p ¼ 0.03. This interaction remained significant in an ANCOVA controlling for prepost changes in positive affect, F(1, 119) ¼ 4.62, MSE ¼ 144.72, p < 0.05, h2p ¼ 0.04 Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 0.30 0.31 0.25 0.06 0.87 0.71 0.21 0.05 0.10 0.15 — 0.75 0.20 0.33 0.34 0.06 0.76 0.93 0.07 0.13 0.18 0.05 — 2 0.22 0.16 0.15 0.04 0.04 0.16 0.16 — 0.00 0.00 3 0.07 0.29 0.03 0.02 0.06 0.14 0.08 — 0.00 4 — — — — 0.06 0.00 0.21 — 5 0.24 0.09 0.21 0.18 — 0.77 0.10 6 0.27 0.16 0.17 0.22 — 0.09 7 0.17 0.16 0.04 0.08 — 8 — 0.10 0.01 0.26 9 — 0.43 0.20 10 — 0.07 11 a p < 0.05; p < 0.01. Dummy codes for the independent variables include, age: 1 ¼ young, 2 ¼ old; gender: 1 ¼ male, 2 ¼ female; condition: 1 ¼ autobiographical memory, 2 ¼ fictional vignette. b Correlations reported only for autobiographical memory condition, n ¼ 64; thus correlations not reported for predictors and condition. Dependent variables 1. Post-memory warmth 2. Post-memory closeness Independent variables 3. Age 4. Gender 5. Condition Covariates 6. Initial levels of warmth 7. Initial levels of closeness 8. Change in positive affect Predictorsb 9. Positive re-experiencing 10. Personal significance 11. Rehearsal 12. Themes of communion 1 Table 2. Correlations between study variablesa — 12 1100 N. Alea and S. Bluck Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1101 Table 3. Cell means and standard deviations for warmth and closeness after remembering by age, gender, and memory condition Male Condition Young Female Old Young Old a Autobiographical memory Fictional vignette 90.24 (16.99) 86.84 (17.83) Autobiographical memory Fictional vignette 94.30 (15.12) 94.43 (13.71) Warmth 92.19 (9.21) 93.27 93.24 (12.17) 89.32 Closenessb 93.48 (14.07) 96.04 94.37 (16.40) 94.01 (4.85) (24.75) 95.46 (13.82) 91.26 (16.32) (14.36) (14.87) 99.07 (10.04) 93.41 (19.08) Note: Estimated marginal means are reported. Standard deviations are in parentheses. a Covariates in model: initial warmth, M ¼ 87.48 and change in positive affect, M ¼ 0.85. Scale ranges from 15 to 105. b Covariates in model: initial closeness, M ¼ 93.72 and change in positive affect, M ¼ 0.85. Scale ranges from 24 to 120. (see Figure 2). A follow up ANCOVA revealed that women, but not men, report more closeness after remembering autobiographical events compared to remembering vignettes, F(1, 60) ¼ 6.44, MSE ¼ 236.91, p < 0.05, h2p ¼ 0.07. No other effects were significant. Do autobiographical memory characteristics affect intimacy gains? The second aim of the study was to explore whether an autobiographical memory must have certain characteristics in order to foster intimacy. To begin this exploration, we conducted an Age Gender MANOVA with the memory characteristics as the dependent variables for the autobiographical memory group. The MANOVA was not significant. Next, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted separately for warmth and closeness to Figure 1. Warmth in the relationship after remembering by memory condition. Note: Estimated marginal means are reported. Covariate in model is initial level of warmth, M ¼ 87.48. Scale ranges from 15 to 105 Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1102 N. Alea and S. Bluck Figure 2. Closeness in the relationship after remembering by gender and memory condition. Note: Estimated marginal means are reported. Covariates in model are initial levels of closeness, M ¼ 93.72 and change in positive affect, M ¼ 0.85. Scale ranges from 24 to 120 examine what memory characteristics predict levels of intimacy after autobiographical remembering. These analyses were conducted only for the autobiographical memory condition (N ¼ 65) as it does not make conceptual sense when testing an intimacy function of autobiographical memory to examine what characteristics of fictional vignette memories predicts levels of intimacy after remembering non-autobiographical vignettes. Given that there were gender differences in levels of closeness in the main intimacy analyses above, we also examined whether memory characteristic interact with gender in predicting post-autobiographical remembering feelings of closeness (and warmth, for consistency). It seemed possible that women and men may be relying on different memory characteristics to serve an intimacy function. Control variables entered in the model first were initial levels of warmth or initial level of closeness, change in positive affect, and verbosity (i.e. a control for word count, as memory content is coded from the narratives). In the next step, main effects were entered in the model, which included gender and memory characteristics (personal significance, positive emotional re-experiencing, rehearsal and themes of communion). In the final step, interaction terms between each memory characteristic and gender was entered. A forward selection procedure (entry criterion ¼ p < 0.05) was used to provide the most parsimonious results (Stevens, 2002) due to the exploratory nature of these analyses (Darlington, 1990). Results for warmth are reported in Table 4. The first step includes variables that are obvious and rather uninteresting predictors of levels of warmth after remembering (e.g. initial levels of warmth). As expected, these control variables accounted for a large percentage of variance, R2 ¼ 0.69, F(3, 59) ¼ 43.15, p < 0.001. Of interest was whether, given that a majority of the variance was accounted for by control variables, memory characteristics would still play a role. Personal significance of the event being remembered was the only significant predictor of feelings of warmth in the relationship after autobiographical remembering, R2 ¼ 0.74, F(1, 58) ¼ 12.96, p < 0.01. Personal significance of the remembered event increased the variance explained by 6%. Recalling more personally significant events predicted higher levels of relationship warmth after autobiographical remembering. None of the other memory characteristics (re-experiencing Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1103 Table 4. Summary of forward regression analyses for memory characteristics and interactions with gender in predicting feelings of warmth after autobiographical remembering (N ¼ 64) B SEB Beta t Warmth Model 1 Initial level of warmth Change in positive affect Verbosity Model 2 Initial level of warmth Change in positive affect Verbosity Personal significance 0.65 0.27 0.00 0.06 0.19 0.00 0.81 0.10 0.06 10.94 1.39 0.86 0.65 0.16 0.00 6.35 0.05 0.18 0.00 1.76 0.80 0.06 0.01 0.25 11.92 0.93 0.10 3.60 Note: Warmth: R2 ¼ 0.69 for Model 1, DR2 ¼ 0.06 for Model 2. Variables statistically excluded from the model were: gender, positive re-experiencing, rehearsal, themes of communion, and the interaction terms. p < 0.01. p < 0.001. positive emotion, rehearsal or communal themes) predicted levels of warmth after remembering; neither did gender or any of the gender by memory characteristic interactions. Results for closeness are reported in Table 5. Control variables again accounted for a large percentage of variance in the model, R2 ¼ 0.81, F(3, 60) ¼ 85.89, p < 0.001. Personal significance was the strongest predictor of feelings of closeness after autobiographical remembering, R2 ¼ 0.84, F(1, 59) ¼ 11.27, p < 0.01, accounting for an additional 3% of the variance. Another memory characteristic, rehearsal, was also a significant predictor of levels of closeness after remembering, R2 ¼ 0.85, F(1, 58) ¼ 4.52, p < 0.05, but accounted for only 1% of the variance. Gender also explained 1% of the variance, R2 ¼ 0.86, F(1, 57) ¼ 4.92, p < 0.05. Two of the interaction terms were significant in predicting levels of closeness after autobiographical remembering. The gender by themes of communion interaction term explained an additional 1% of the variance, R2 ¼ 0.87, F(1, 56) ¼ 5.68, p < 0.05. The rehearsal and gender main effects were qualified by a significant interaction between gender and rehearsal, R2 ¼ 0.88, F(1, 55) ¼ 4.28, p < 0.05, and accounted for 1% of the variance in the model. To better interpret these interactions, follow-up partial correlations (controlling for initial levels of closeness) between themes of communion and rehearsal, and levels of closeness after remembering were conducted for each gender separately. For men, there was no relation between communal themes (r ¼ 0.02, p > 0.05) or rehearsal (r ¼ 0.03, p > 0.05) and levels of closeness after autobiographical remembering. Women, however, who remembered events that were frequently thought and talked about (r ¼ 0.65, p < 0.05), and had memories that were rich in intimate content (i.e. communal themes; r ¼ 0.42, p < 0.05), were more likely to experience gains in closeness after autobiographical remembering.4 4 Regression analyses were conducted to examine the possibility that rating one’s relationship intimacy created post hoc effects on rating memory characteristics. Levels of warmth did not predict level of personal significance of participants’ memories. Levels of closeness did not predict level of personal significance, amount of rehearsal or communal themes in a participant’s memory. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1104 N. Alea and S. Bluck Table 5. Summary of forward regression analyses for memory characteristics and interactions with gender in predicting feelings of closeness after autobiographical remembering (N ¼ 64) Model 1 Initial levels of closeness Change in positive affect Verbosity Model 2a Personal significance Model 3 Personal significance Rehearsal Model 4 Personal significance Rehearsal Gender Model 5 Personal significance Rehearsal Gender Gender Communal themes Model 6 Personal significance Rehearsal Gender Gender Communal themes Gender Rehearsal B SEB Beta t 0.88 0.10 0.00 0.06 0.16 0.00 0.89 0.04 0.07 15.78 0.63 1.16 5.10 1.52 0.19 3.36 3.68 2.59 1.62 1.22 0.14 0.12 2.27 2.13 2.69 2.87 3.15 1.63 1.19 1.42 0.10 0.13 0.12 1.65 2.42 2.22 2.12 2.72 1.11 0.72 1.59 1.14 1.61 0.30 0.07 0.13 0.04 0.14 1.34 2.38 0.69 2.38 1.79 3.48 10.63 0.65 4.19 1.55 3.20 5.88 0.29 2.02 0.07 0.16 0.39 0.13 0.54 1.16 1.09 1.81 2.22 2.07 Note: Closeness: R2 ¼ 0.81 for Model 1, DR2 ¼ 0.03 for Model 2, DR2 ¼ 0.01 for Model 3, DR2 ¼ 0.01 for Model 4, DR2 ¼ 0.01 for Model 5, DR2 ¼ 0.01 for Model 6. Variables statistically excluded from the model were positive re-experiencing, themes of communion, and the gender personal significance and gender positive re-experiencing interactions. a Control variables are not presented throughout the table; initial levels of closeness was the only variable that remained significant as each new predictor was selected for inclusion. p < 0.05. p < 0.01. p < 0.001. DISCUSSION Humans are inherently social, as having intimate romantic relationships is a goal most people aspire toward (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Erikson, 1980). There are multiple avenues for maintaining intimacy when couples are together (i.e. through mutual conversation, touching etc.; Laurenceau et al., 1998). But, how is intimacy maintained when couples are apart? Remembering good times spent with one’s partner is one way to keep one’s partner close in their absence. Though much theorized about, the current study is the first experimental evidence that autobiographical remembering serves an intimacy function. Remembering only two personally meaningful relationship events about one’s partner (in their absence) led to increased feelings of warmth (marginally significant when concomitant changes in positive affect are removed). Thus, autobiographical remembering fosters emotional warmth in the relationship simultaneous with a general increase in positive affect. People feel better in general, but also feel more warmth in their relationship. Enhanced relationship closeness as a function of autobiographical remembering is evident in women, and, occurs Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1105 independently of changes in positive affect. Note that the control condition demonstrates that it is the autobiographical component of memories that ‘makes the heart grow fonder’. Remembering non-autobiographical relationship events that were similar in quality, structure, and content (Dixon et al., 1989) did not enhance intimacy. The memory trace (Larsen, 1998) needs to be autobiographical. Further study findings are highlighted below with a focus on the role of the rememberer and memory characteristics when using autobiographical memory to enhance intimacy. Note that the pattern of findings does not suggest an unconditional role for memory in serving an intimacy function. Instead, characteristics of both the rememberer and the remembered episode itself are critical to such a function being served. Age continuity in the intimacy function of autobiographical memory One focus of this study was to examine whether the age of the person remembering would affect the extent to which autobiographical remembering enhanced relationship intimacy. We hypothesized that sustaining intimate romantic relationships may be consistent with life phase tasks in both early and late life, and be so fundamental to socio-emotional well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Carstensen et al., 1999), that the intimacy function would be evident in young adulthood and preserved in late life. Results confirm this hypothesis, as autobiographical remembering led to greater feelings of warmth regardless of age, and enhanced feelings of closeness for young and old women. Remembering specific relationship events, like the day one met their spouse, can foster intimacy in relationships at 20 or 70. The power of the event does not seem to diminish over time, as one might predict (i.e. affect fading effect; Walker, Skowronski, & Thompson, 2003). Despite other age-related memory declines (see Zacks et al., 2000), autobiographical memory maintains its functional role in the lives of older adults (Cohen, 1998). Age of the person (and related age of the memory) does not diminish the impact that recall of special relationship moments has for a person’s sense of intimacy. This result fits neatly within the lifespan psychology framework (e.g. Baltes, 1987; Baltes et al., 1999) in that understanding adult development, documenting stability (i.e. no age differences) is as important as documenting change. Future work that includes middle-aged individual’s is needed to examine whether autobiographical memory serves an intimacy function across adulthood or only during particular stages (e.g. young adulthood, older adulthood) when developmental tasks coincide with intimacy goals (Erikson, 1980; Neugarten, 1979). The intimacy function of autobiographical memory may be less salient in midlife, at least for romantic relationships, as developmental tasks such as having children and establishing a career are at the forefront of psychosocial development (Staudinger & Bluck, 2001). Gender differences in the intimacy function of autobiographical memory After autobiographical remembering, both men and women reported enhanced warmth in their relationship. As expected, however, women experienced broader gains, also reporting enhanced closeness in their relationship. Thus, after autobiographical remembering women not only experience increase in the momentary affective feelings about the relationship, but also change their perception about how they function as an interdependent (i.e. close) unit. Women’s view of their relationship appears to be more malleable, and reliant on current perceptions. They are willing to reassess the relationship, so that Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1106 N. Alea and S. Bluck remembering only two autobiographical relationship events can change their perceptions, leading to increased feelings of closeness. This finding bridges work demonstrating that women are more focused on actively sustaining intimate ties (for a review see Reis, 1998) with results showing that women sometimes (though not always; e.g. Rubin et al., 1999) place more emphasis on remembering life events (e.g. Davis, 1999; de Vries & Watt, 1996; Niedzwienska, 2003; Pillemer et al., 2003; Pohl, Bender, & Lachmann, 2005). For women, memories about positive, meaningful relationship events may be a key mechanism that is utilized in sustaining relationships. For example, remembering the first date with one’s husband may be accessed during good times as evidence for relationship-continuity, and during difficult times, as a way to remain hopeful about the relationship. Such memories may be accessed when the husband is away, whether at work for the day, or at war for months or years. Thus, women may be more motivated towards intimacy in a variety of contexts (Reis, 1998) and autobiographical remembering is a tool or resource that they use to achieve their intimacy-related goals. Specific characteristics allow autobiographical memory to serve an intimacy function Most theorists agree that not every remembered experience serves important socioemotional functions (e.g. Alea & Bluck, 2003; Baddeley, 1987; Bruce, 1989). We investigated whether certain memory characteristics (i.e. personal significance, rehearsal, emotional re-experiencing, themes of communion) are related to greater gains in intimacy. Emotional re-experiencing of an event was not necessary to foster intimacy in a relationship. Consistent with study hypotheses, memories with greater personal significance led to higher levels of both warmth and closeness after remembering. Personal significance of an event has been related to memory performance in terms of how completely and clearly a memory is recalled (e.g. Bluck et al., 1999; Cohen, Conway, & Maylor, 1994). Remembering personally significant events is sufficient to foster feelings of warmth in the relationship for men, and is relevant for women. The broader gains in intimacy that women experience as a function of autobiographical remembering (i.e. both warmth and closeness), rely on them recalling certain types of memories. Women may have a set of ‘relationship-defining memories’ (N. Alea & J. A. Singer, personal communication, 21 August 2005), a core set of meaningful memories about their relationship (i.e. personally significant, high in communal themes) that they rehearse (i.e. tell to themselves or others) that enhance closeness. For women to experience broad gains in relationship closeness, it is these relationship-defining memories that they need to recall. This research provides the first evidence to support the link between particular memory characteristics and the socio-emotional functions that memory serves (Alea & Bluck, 2003; Pillemer, 1998). Study limitations and future directions The experimental pre-post design used in the current research has several advantages over previously used self-report measures (i.e. Bluck et al., 2005; Webster, 1995). It moves closer to the way that the intimacy function may be served in everyday life, and it is a conservative test of memory’s role in enhancing intimacy since it involves measuring changes in intimacy after remembering only two brief relationship events. This design, Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1107 however, might be considered a drawback and leaves open questions for future research. First, although we made every attempt to reduce demand characteristics (i.e. through comparison condition, recruitment strategies, ordering of study measures), it is possible that increases in intimacy after autobiographical remembering were due to demand. The lack of differential increases across conditions from pre- to postremembering on the PAIR Conventionality subscale reduces this concern, but it cannot be completely discounted. Second, the study design does not allow claims about the generalizability of the intimacy function across all types of relationship events. For example how might remembering negative relationship events, like an argument with one’s spouse, influence feelings of intimacy? Another direction for future work is to examine whether the accuracy of autobiographical memory influences the extent to which an intimacy function is served. It may be that enhancement biases in autobiographical memory are adaptive in meeting fundamental socio-emotional goals, and remembering our relationships in a positive, though inaccurate, light is related to relationship satisfaction (e.g. Karney & Coombs, 2000). Future research systematically varying the above-mentioned memory characteristics (e.g. emotional valence, content, accuracy), or other model variables (Alea & Bluck, 2003), such as the role of the listener (e.g. level of responsiveness), or who the listener is (i.e. stranger vs. loved one, someone of same or different age or gender) will allow for a deeper and broader understanding of how autobiographical memory is best used to foster intimacy. A final area for future work is to explore cognitive mechanisms that might be related to feelings of intimacy as a function of autobiographical remembering. Finding that people feel more intimate after remembering relationship events seems consistent with a loose definition of associative priming (La Voie & Light, 1994) or use of a judgement heuristic (Clore & Parrott, 1991). A transitory mental representation (memory about a person) primes or biases a person to feel a particular way (more intimate). Both explanations have been given for the mood-congruent memory effect (Fiedler et al., 2001). These cognitive mechanisms, however, cannot completely explain our results. First, although emotional re-experiencing at recall is related to memory vividness (Schaefer & Philippot, 2005), it did not predict memory function (i.e. gains in intimacy), providing some preliminary evidence that it is not the emotionality of a remembered relationship event that ‘primes’ (La Voie & Light, 1994) individuals to feel more emotional in general and thus report greater intimacy. Further, although participants recalled positive events, the events varied in level of intimacy (e.g. honeymoons to family vacations). They were not laden with intimate content (i.e. M ¼ 2.70 out of a possible score of 8), and intimate content only predicted post-remembering closeness for women. Thus, priming cannot be the only basic cognitive mechanism that accounts for our effects. Conclusion: keeping loved ones in mind keeps them close in one’s heart Humans do not remember everything, but they do recall huge amounts about their experiences in important relationships with others. Memories of relationship events come freely to mind. Memories of loved ones stay with us for years. What purpose or function might memories of loved ones serve in keeping intimacy alive in relationships? Based on a conceptual model of how and when autobiographical memory serves social functions, the current research provides evidence that autobiographical memory can be used to foster intimacy in relationships. Results suggest that using recall of autobiographical events to foster intimacy is well-preserved across adulthood, and that the extent to which Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1108 N. Alea and S. Bluck autobiographical memory fosters intimacy may depend on gender-related socio-emotional goals. Not all types of memories, however, produce gains in intimacy. Personal significance of the memory is critical to enhancing intimacy, and rehearsal and intimate content are necessary for women. Our conceptual model provides a basis for further empirical investigations of how, when, and by whom autobiographical memory is used to serve important social goals in everyday life. Among other things, such research will provide further understanding of how keeping loved ones in mind can keep them close in one’s heart. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Predoctoral Minority Fellowship awarded to Nicole Alea from the National Institute on Aging, grant number 1 F31 AG20505. The authors extend their appreciation the research assistants at the Life Story Lab at the University of Florida. REFERENCES Acitelli, L. K., & Antonucci, T. C. (1994). Gender differences in the link between marital support and satisfaction in older couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 688–698. Alea, N. (2004). I’ll keep you in mind: The intimacy function of autobiographical memory across adulthood. Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida. Alea, N., & Bluck, S. (2003). Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory, 11, 165–178. Anderson, S. J., Cohen, G., & Taylor, S. (2000). Rewriting the past: Some factors affecting the variability of personal memories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 14, 435–454. Baddeley, A. (1987). But what the hell is it for? In M. M. Gruneberg, P. E. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory: Current research and issues (Vol. 1, pp. 3–18). Chichester, England: Wiley. Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23, 611–626. Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan psychology: Theory and application to intellectual functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471–507. Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. Belove, L. (1980). First encounters of the close kinds (FECK): The use of the story of the first interaction as an early recollection of a marriage. Individual Psychologist, 36, 191–208. Bluck, S., & Alea, N. (2002). Exploring the functions of autobiographical memory: Why do I remember the autumn. In J. D. Webster, & B. K. Haight (Eds.), Critical advances in reminiscence theory: From theory to application (pp. 61–75). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. Bluck, S., Alea, N., Habermas, T., & Rubin, D. C. (2005). A TALE of three functions: The self-reported uses of autobiographical memory. Social Cognition, 23, 91–117. Bluck, S., & Habermas, T. (2001). Extending the study of autobiographical memory: Thinking back about life across the life span. Review of General Psychology, 5, 135–147. Bluck, S., Levine, L. J., & Laulhere, T. M. (1999). Autobiographical remembering and hypermnesia: A comparison of older and younger adults. Psychology and Aging, 14, 671–682. Bluck, S., & Li, K. Z. H. (2001). Predicting memory completeness and accuracy: Emotion and exposure in repeated autobiographical recall. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, 145–158. Bohannon, J. N. (1988). Flashbulb memories for the space shuttle disaster: A tale of two theories. Cognition, 29, 179–196. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1109 Bruce, D. (1989). Functional explanations of memory. In L. W. Poon, D. C. Rubin, & B. A. Wilson (Eds.), Everyday cognition in adulthood and late life (pp. 44–58). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 209–254). Lincoln: University of Nebraska. Carstensen, L. L., Graff, J. M., Levenson, R. W., & Gottman, J. M. (1995). Affect in intimate relationships: The developmental course of marriage. In C. Magai, & S. H. McFadden (Eds.), Handbook of emotion, adult development, and aging (pp. 227–247). San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc. Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181. Cliff, N., & Hamburger, C. D. (1967). The study of sampling errors in factor analysis by means of artificial experiments. Psychological Bulletin, 68, 430–445. Clore, G. L., & Parrott, W. G. (1991). Moods and their vicissitudes: Thoughts and feelings as information. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Emotion and social judgments (pp. 107–123). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Cohen, G. (1998). The effects of aging on autobiographical memory. In C. P. Thompson, D. J. Herrmann, D. Bruce, D. J. Read, D. G. Payne, & M. P. Toglia (Eds.), Autobiographical memory: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 105–123). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Cohen, G., Conway, M., & Maylor, E. A. (1994). Flashbulb memories in older adults. Psychology & Aging, 9, 454–463. Darlington, R. B. (1990). Regression and linear models. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Davis, P. J. (1999). Gender differences in autobiographical memory for childhood emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 498–510. de Vries, B., & Watt, D. (1996). A lifetime of events: Age and gender variations in the life story. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 42, 81–102. Dixon, R. A., Hultsch, D. R., & Hertzog, C. (1989). A manual of twenty-five three-tiered structurally equivalent texts for use in aging research (Tech. Rep. No. 2). Collaborative Research Group on Cognitive Aging, University of Victoria. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Fehr, B. (2004). A prototype model of intimacy interactions in same-sex friendships. In D. J. Mashek, & A. Aron (Eds.), Handbook of closeness and intimacy Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Fiedler, K., Nickel, S., Muehlfriedel, T., & Unkelbach, C. (2001). Is mood congruency an effect of genuine memory or response bias? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 201– 214. Gorsuch, R. L. (1983). Factor analysis. (2nd ed., pp. 291–309). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Heiman, G. W. (2001). Understanding research methods and statistics. An integrated introduction for psychology. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. Hickmon, W. A., Protinsky, H. O., & Singh, K. (1997). Increasing marital intimacy: Lessons from marital enrichment. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 19, 581–589. Holmberg, D., Orbuch, T. L., & Veroff, J. (2004). Thrice-told tales: Married couples tell their stories. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Hyman, I. E., & Faries, J. M. (1992). The functions of autobiographical memory. In M. A. Conway, D. C. Rubin, H. Spinnler, & J. W. A. Wagenar (Eds.), Theoretical perspectives on autobiographical memory (pp. 207–221). The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of the electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151. Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1997). Neuroticism, marital interaction and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1075–1092. Karney, B. J., & Coombs, R. H. (2000). Memory bias in long-term close relationships: Consistency or improvement? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 959–970. La Voie, D., & Light, L. L. (1994). Adult age differences in repetition priming: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 9, 539–553. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp 1110 N. Alea and S. Bluck Lang, F. R. (2001). Regulation of social relationships in later adulthood. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 56, P321–P326. Larsen, S. F. (1998). What is it like to remember? On phenomenal qualities of memory. In C. P. Thompson, D. J. Herrmann, D. Bruce, D. J. Read, D. G. Payne, & M. P. Toglia (Eds.), Autobiographical memory: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 163–190). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Laurenceau, J. P., Barrett, L. F., & Pietromonaco, P. R. (1998). Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1238–1251. Maddox, G. L. (1962). Some correlates of differences in self-assessment of health status among the elderly. Journal of Gerontology, 17, 180–185. Mashek, D. J., & Aron, A. (2004). Handbook of closeness and intimacy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. McAdams, D. P. (1984). Experiences of intimacy and power: Relationships between social motives and autobiographical memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 292–302. McAdams, D. P. (2001). Coding autobiographical episodes for themes of agency and communion. The Foley Center for the Study of Lives, Northwestern University. Evanston, IL. McAdams, D. P., Hoffman, B. J., Mansfield, E. D., & Day, R. (1996). Themes of agency and communion in significant autobiographical scenes. Journal of Personality, 64, 339–377. Niedzwienska, A. (2003). Gender differences in vivid memories. Sex Roles, 49, 321–331. Neisser, U. (1978). Memory: What are the important questions? In M. M. Gruneberg, P. I. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory (pp. 3–19). London: Academic Press. Nelson, K. (1993). The psychological and social origins of autobiographical memory. Psychological Science, 4, 7–14. Neugarten, B. L. (1979). Time, age, and the life cycle. American Journal of Psychiatry, 136, 887–894. Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 141–151. Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957). The measurement of meaning. Urbana, IL: University Illinois Press. Pasupathi, M. (2001). The social construction of the personal past and its implication for adult development. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 651–672. Pasupathi, M., Lucas, S., & Combs, A. (2002). Function of autobiographical memory in discourse: Long-married couples talk about conflicts and pleasant topics. Discourse Process, 34, 163–192. Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1991). Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Pillemer, D. (1998). Momentous events: Vivid memories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Pillemer, D., Wink, P., DiDonato, T. E., & Sanborn, R. L. (2003). Gender differences in autobiographical memory styles of older adults. Memory, 11, 525–532. Pohl, R. F., Bender, M., & Lachmann, G. (2005). Autobiographical memory and social skills of men and women. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19, 745–759. Reis, H. T. (1998). Gender differences in intimacy and related behaviors: Context and process. In D. J. Canary, & K. Dindia (Eds.), Sex differences and similarities in communication: Critical essays and empirical investigations of sex and gender in interaction (pp. 203–231). Mahaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Reis, H. T., & Shaver, P. (1988). Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In S. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships (pp. 367–389). Chichester, England: Wiley. Rey, A. (1941). L’examen psychologique dans les cas d’encephalopathie tramatique. Archives de Psychologie, 28, 21. Roccafort, W. H., Burke, W. J., Bayer, B. L., & Wengel, S. P. (1992). Validation of a telephone version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40, 697–702. Ross, M., & Holmberg, D. (1992). Are wives’ memories for events in relationships more vivid than their husbands’ memories? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9, 585–604. Rubin, D. C., Schulkind, M. D., & Rahhal, T. A. (1999). A study of gender differences in autobiographical memory: Broken down by age and sex. Journal of Adult Development, 6, 61–71. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp Intimacy function of memory 1111 Schaefer, M. T., & Olson, D. H. (1981). Assessing intimacy: The PAIR Inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7, 47–60. Schaefer, A., & Philippot, P. (2005). Selective effects of emotion on the phenomenal characteristics of autobiographical memory. Memory, 13, 148–160. Shaffer, D. R., Pegalis, L. J., & Bazzini, D. G. (1996). When boy meets girl: Gender, gender-role orientation, and prospect of future interaction as determinants of self-disclosure among same and opposite-sex acquaintances. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 495–506. Schaie, K. W. (1994). The course of adult intellectual development. American Psychologist, 49, 304–313. Sloan, D. M., Marx, B. P., & Epstein, E. M. (2005). Further examination of the exposure model underlying the efficacy of written emotional disclosure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 549–554. Staudinger, U. M. (2001). Life reflection: A social-cognitive analysis of life review. Review of General Psychology, 5, 148–160. Staudinger, U. M., & Bluck, S. (2001). A view on midlife development from life-span theory. In M. E. Lachman (Ed.), Handbook of midlife development (pp. 3–39). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Stevens, J. P. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (4th ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Thurstone, T. G. (1962). Primary mental ability for Grades 9-12 (Rev. Ed.). Chicago IL: Science Research Associates. Walker, W. R., Skowronski, J. J., & Thompson, C. P. (2003). Life is pleasant-and memory helps keep it that way. Review of General Psychology, 7, 203–210. Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scale. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. Webster, J. D. (1995). Adult age differences in reminiscence functions. In B. K. Haight, & J. D. Webster (Eds.), The art and science of reminiscing: Theory, research, methods, and applications (pp. 89–102). Washington, D.C: Taylor and Francis. Wechsler, D. (1981). Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Psychological Corporation: New York. Winograd, E., & Neisser, U. (1992). Affect and accuracy in recall: Studies of ‘flashbulb’ memories. Cambridge University Press. Woike, B., Gershkovich, I., Piorkowski, R., & Polo, M. (1999). The role of motives in the content and structure of autobiographical memory. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 76, 600–612. Zacks, R. T., Hasher, L., & Li, K. Z. H. (2000). Human memory. In F. I. M. Craik, & T. A. Salthouse (Eds.), The handbook of aging and cognition (2nd ed., pp. 293–357). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Copyright # 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 21: 1091–1111 (2007) DOI: 10.1002/acp