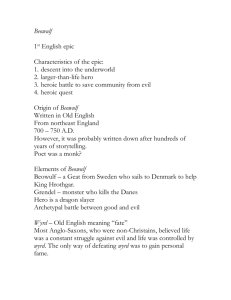

Monsters and Heroes in the Named Lands of the North

advertisement