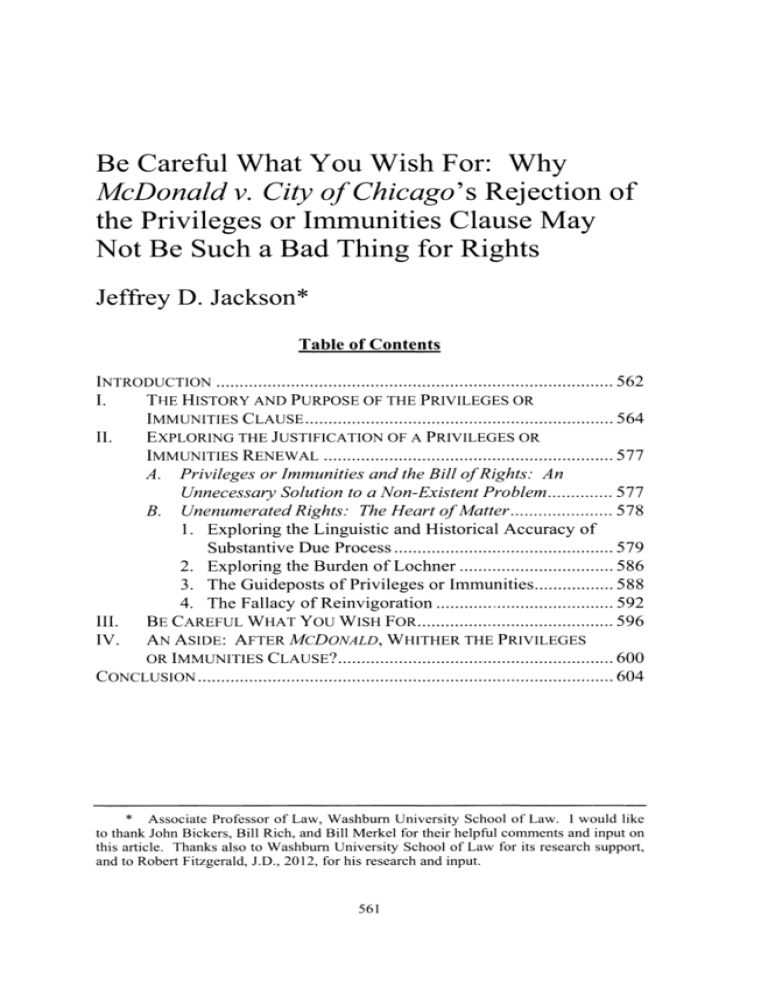

Be Careful What You Wish For: Why McDonald v. City of Chicago's

advertisement