Independent External Evaluation of The Columbia Basin Water

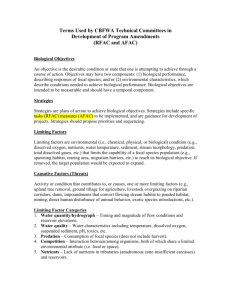

advertisement