Conceptions of Justice and Morality in The Epic of Gilgamesh and

advertisement

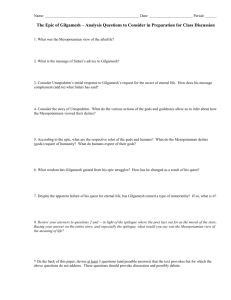

Conceptions of Justice and Morality in The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Oresteia By Brian Kim HIST435 - Western Civilization Professor McMahon 10/18/13 Kim 1 The analyses of fiction and legend throughout history provide a rich and powerful window through which the cultures of civilizations can be studied. Works that become popularized within an era reflect not only the tastes of the audience they appeal to, but also the values and worries of said audience. Further, the sentiments of authors, and the issues they deem important enough to write about, present additional testament to the cultural relevance of their work. For example, the content of The Epic of Gilgamesh shows that Mesopotamians were grappling with the ideas of mortality and brotherhood – indeed, ideas that we continue to grapple with even today. Likewise, The Oresteia demonstrates the Greeks’ conceptions of the gods and their dynamics of family. Though rife with sociological information, we can also inspect these works from a more judicially focused lens. Running throughout both of these tales is a common question: what is justice, and how is it exacted? Why must Enkidu and Gilgamesh be punished for their actions? And why is Orestes considered innocent by Athena? By examining these issues within the two stories, we can define what constitutes crime and morality for these civilizations, and ultimately trace a lineage for the judicial process from the more religiously focused and patronizing system of the Mesopotamians, to the nuanced and complex inquiries of the Greeks. To begin our examination, it is perhaps best to start chronologically with Gilgamesh’s treatment of his people in The Epic of Gilgamesh. Described as a tyrant, Gilgamesh ruled the city Uruk without restraint over his actions, taking wives on their wedding nights and doing as he pleased.1 Though the translations vary with regard to Gilgamesh’s precise actions, the pleading of the people to the gods immediately defines Gilgamesh’s overall manner as immoral and undesirable, further reinforced by the gods’ decision to create Enkidu as a tool to rein Gilgamesh 1 Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh, comp. Wolf Carnahan, n.p.: n.p., n.d. Academy for Ancient Texts, Web. 17 Oct. 2013, <http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/>, Tablet 1. Kim 2 in.2 Unlike what we will see with The Oresteia, morality in The Epic of Gilgamesh seems to be more cleanly defined, determined primarily by the gods and without ambiguity. Though the people were the ones to raise the complaint, it was ultimately the gods that decided that Gilgamesh needed adjustment, and the reader is not left to wonder whether such a decision is justified. The story is simplistic in this regard, presenting a clear crime and a clear punishment, and thus a clear moral tenet for the audience to take away – treat your people with civility and respect. This trend of clarity is continued with regards to Enkidu’s eventual death – because Gilgamesh and Enkidu slayed the Bull of Heaven and Humbaba, Enkidu was forced to pay with his life.3 Though Shamash raised issue with the punishment, his arguments were silenced and voided once the punishment was actually doled out. In this case, the disrespect Gilgamesh and Enkidu showed to the gods through their actions was painted as a clear offense, the only ambiguity being whether or not Shamash was partly to blame for his influence on them. Because the gods are depicted as the ultimate arbiters of what is right and wrong, the audience is yet again left without the option to refute their ruling and understands disrespect against the gods as a crime. If even the great Enkidu and Gilgamesh could not stand against the ruling of the gods, why would the common individual attempt to? This clarity is in part due to the style of writing that The Epic of Gilgamesh is written in; the repetition often used throughout the tablets is indicative of a story that was primarily spread via spoken word, especially given the relatively recent development of writing and literacy. Paired with the strong sense of morality imposed by Gilgamesh’s adventures, Gilgamesh functions largely as a set of parables spread throughout the population – do not try to avoid 2 3 The Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet 1. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet 7. Kim 3 death, do not disrespect the gods, do not act savagely to each other. However, even with this caveat the story is still hugely reflective of a society that places heavy emphasis on reverence towards the gods, with a system of justice that revolves not around human affairs, but religious affairs – not debatable issues established by man, but immutable truths established, at least conceptually, by gods. One need only notice that Gilgamesh’s injustices against his people were not punished nearly as harshly as his offenses against the gods, if the creation of Enkidu is even to be considered a punishment at all. Further, the fact that the people beseech the gods for an answer to Gilgamesh’s behavior suggests that they were without any form of established legal recourse in the face of Gilgamesh’s strength. This is of course not to imply that there were no laws in Mesopotamian society other than what was outlined in Gilgamesh, but this is representative of a culture that did not yet grapple with the intense complexity of morality in an individualized sense. What we uncover about Mesopotamian culture and thought from The Epic of Gilgamesh is in stark contrast to what we find about Greek culture via Aeschylus’ The Oresteia, and the juxtaposition of the two stories provides a great deal of insight about the progression of governmental thought that occurred between the two civilizations. Even conceptually, the moral issues raised by Aeschylus are far more complex than those raised in The Epic of Gilgamesh, with multiple levels of vengeance and wrong-doing occurring throughout. It isn’t nearly as simple as one crime invoking a specific punishment – quite the opposite, as Aeschylus asks whose morality is the correct morality, and whose punishments are the just punishments. Each actor in the play works off their own sense of right and wrong, each seeking to exact justice in their own, and largely logical, way. Kim 4 Clytemnestra ultimately seeks justice for the sacrifice of her daughter, Iphigenia, at the hands of Agamemnon in his voyage to Troy.4 The case she makes is both emotional and horrifying, as she imagines the scene of her daughter’s death: “They gagged her lovely mouth / with force, just like a horse’s bit, / to keep her speechless, to stifle any curse / which she might cry against her family.”5 On reading this section there can be no doubt that Clytemnestra’s grievances against Agamemnon are valid from the mother’s perspective – yet one could just as easily side with Agamemnon. Though his reasons for waging war against Troy could be called into question, given that he had mobilized the Greek forces, his decision to sacrifice Iphigenia to Artemis could be seen as an act of necessity, rather than the act of brutality that Clytemnestra saw.6 To further complicate matters, the morality of Clytemnestra’s actions has immediate consequences for the morality of Orestes’ actions – if Clytemnestra is justified in killing Agamemnon, Orestes is unjustified in killing Clytemnestra, and vice versa. That said, the conception of justice in The Oresteia is magnitudes more nuanced than in The Epic of Gilgamesh in this capacity alone, and it becomes even moreso because of the fallibility of all the actors. Whereas in The Epic of Gilgamesh, moral judgment was left out of the hands of the reader and left as an absolute due to the decisions of the gods, Aeschylus leaves his inquiry much more open-ended. Though Orestes is vindicated by Athena’s tie-breaking vote, the very presence of dissenting opinions in the judges offers the reader justification for siding with either party, and the heated arguments between the Furies and Apollo leave more room for readers to disagree with the gods if they feel it necessary.7 Though the involvement of the gods is 4 Aeschylus. The Oresteia. trans. Ian Johnston, N.p.: n.p., n.d. Johnstonia, Vancouver Island University, Web. 17 Oct. 2013, <https://records.viu.ca/~Johnstoi/aeschylus/oresteiatofc.htm>, lines 250-290. 5 The Oresteia, l. 276-280. 6 The Oresteia, l. 235-240. 7 The Oresteia, l. 850-950. Kim 5 still a huge cornerstone of Aeschylus’s work, and thus reflective of their importance in Greek culture, they are by no means infallible. Aeschylus also works to brings in evidence throughout the case that begs several incredibly delicate questions: how does blood relation alter the severity of a murder? Does killing one’s own blood in the name of country stand as more honorable than killing one’s own blood in the name of family? To what extent is patricide more despicable than matricide? These are questions that the gods do not settle outright as determinations for the audience, as occurs in Gilgamesh, but rather questions that Aeschylus raises to the people of Greece. By corollary, this reflects an audience that is capable of answering these questions for themselves. Whereas The Epic of Gilgamesh acts as parables that are meant to be followed rather strictly, The Oresteia merely raises the issues for discussion and debate, and it creates an image of justice and law in Greek society that is decidedly more human and logic-centric, demonstrated even further by Athena’s creation of the court – which is, in a very real sense, the gods handing down the role of judgment to the humans. Analysis of these works is by no means a substitute for direct analysis of historical events and artifacts, but they provide an excellent companion to supplement and deepen our understanding of what we already know. Mesopotamian culture was obviously heavily dependent on religious teachings and spirituality in their day-to-day life, while the Greeks signified a shift away from that extreme. One might point to Aeschylus’ trust in the audience as an indicator of increased access to education and greater political discourse as a natural byproduct of Solon and Cleisthenes’ reforms – something that the audience for Gilgamesh clearly would not have had. The idea of individualizing morality in this way is also unique to the Greeks, offering up to the audience to decide whether or not Orestes was justified in his actions. Kim 6 The two stories provide an excellent contrast to one another, and allow us to glean a great deal of insight into the transitions between these two civilizations. Kim 7 Bibliography Aeschylus. The Oresteia. Trans. Ian Johnston. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Johnstonia. Vancouver Island University. Web. 17 Oct. 2013. <https://records.viu.ca/~Johnstoi/aeschylus/oresteiatofc.htm>. Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Comp. Wolf Carnahan. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Academy for Ancient Texts. Web. 17 Oct. 2013. <http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/>.