Psychology Aotearoa - The New Zealand Psychological Society

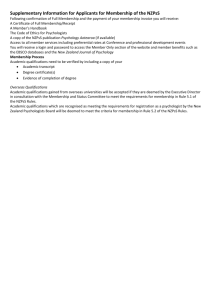

advertisement