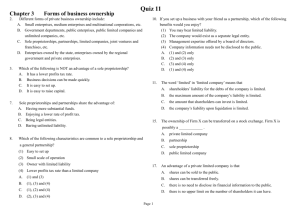

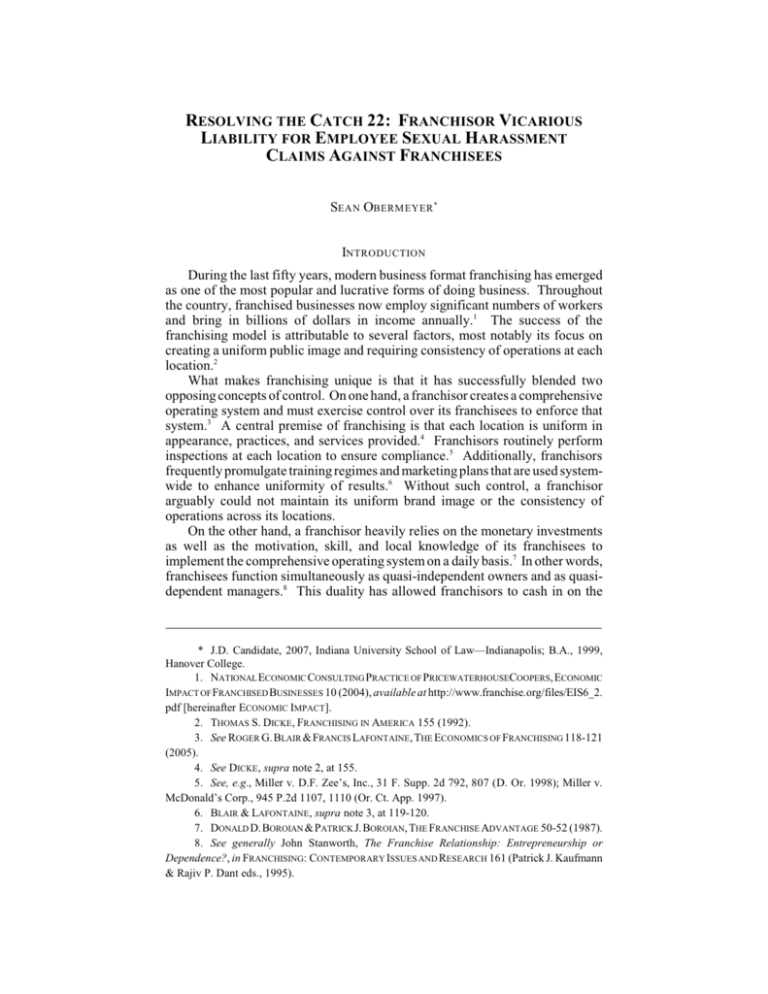

RESOLVING THE CATCH 22 - Robert H. McKinney School of Law

advertisement