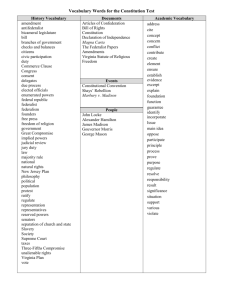

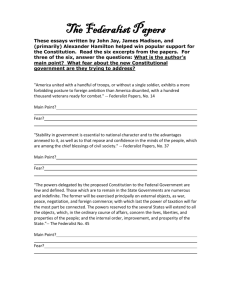

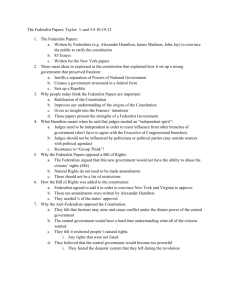

The Federalist Papers

advertisement