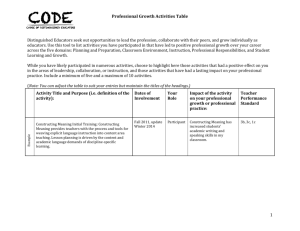

Constructing Measures

advertisement