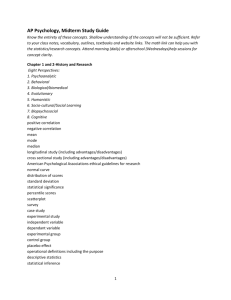

Introductory Psychology – Unit 2

advertisement