Interstate Commerce Act Munn v. Illinois (1877) Elkins Act (1903)

advertisement

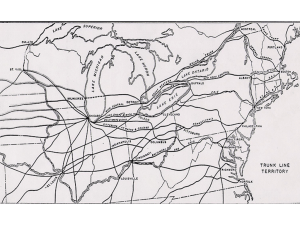

Federal Government Interstate Commerce Act 1887 - The First Cleveland Administration During the 1870s, many Americans (particularly farmers) began to resent the apparent stranglehold the railroads exerted over many parts of the country. However, the postwar presidents and many in Congress resisted intervention in economic matters. Early efforts to bring some form of regulation to the giants were made at the state level, but those measures were later struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1887, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act which created the Interstate Commerce Commission, the first true federal regulatory agency. It was designed to address the issues of railroad abuse and discrimination and required the following: • • • • Shipping rates had to be "reasonable and just" Rates had to be published Secret rebates were outlawed Price discrimination against small markets was made illegal. Although the law granted the Commission power to investigate abuses and summon witnesses, it lacked the resources to accomplish its lofty goals. Later presidents would assure that reform would not go too far, by appointing pro-railroad commissioners. Munn v. Illinois (1877) The Granger Cases During the height of the 1870s depression, the Illinois legislature responded to the pleas of embattled farmers by enacting a law that established a maximum charge that could be imposed by grain storage facility operators and railroad companies. The matter was contested in the courts and found its way to the Supreme Court in 1876 and was finally decided by a 7-2 vote, in March 1877. The majority upheld the Illinois law and reasoned that a state has a legitimate police power to regulate private enterprises that may adversely impact the public interest (including railroads). The Court refused to accept the operators' arguments that the due process clause had been violated or that a state role in commerce regulation clashed with the Congressional role. Munn v. Illinois introduced a short era in which U.S. public utilities (including railroads) were subjected to increased scrutiny. The Court later upheld state efforts to regulate railroad rates. Critics bemoaned the growth of socialism in the country, fearing that private enterprise was being hobbled. Elkins Act (1903) The Elkins Act ended the common practice of the railroads granting rebates to their most valued customers. The great oil and livestock companies of the day paid the rates stated by the railroads, but demanded rebates on those payments. The giants paid significantly less for rail service than farmers and other small operators. The railroads had long resented being extorted by the trusts and welcomed the Elkins legislation. The law provided further that rates had to be published and that violations of the law would find both the railroad and the shipper liable for prosecution. This measure brought some improvement, but other abuses needed to be addressed. Hepburn Act (1906) The Hepburn Act strengthened existing railroad regulations in the following ways: 1. Increased the size of the Interstate Commerce Commission from five to seven members 2. Gave the ICC the power to establish maximum rates 3. Restricted the use of free passes 4. Brought other common carriers (businesses that transport goods or information for a fee), such as terminals, storage facilities, pipelines, ferries and others, under ICC jurisdiction 5. Required the adoption of uniform accounting practices for all carriers 6. In appeals situations, placed the burden of proof on the shipper, not the ICC; this was a major change from the previous practice in which the railroads had blunted regulations by lengthy appeals. President Roosevelt was a major factor in securing passage of this measure; he countered the furious opposition of the railroads and many other parts of the business community. Source: http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h743.html The Children's Bureau The Creation of the Children's Bureau The Children's Bureau was formally created in 1912 when President William Howard Taft signed into law a bill creating the new federal government organization. The stated purpose of the new Bureau was to investigate and report "upon all matters pertaining to the welfare of children and child life among all classes of our people." The signing of this law culminated a grass-roots process started in 1903 by two early social reformers, Lillian Wald, of New York's Henry Street Settlement House, and Florence Kelly, of the National Consumer's League. Along the way, their efforts picked up support from President Theodore Roosevelt, among other prominent supporters, before finally becoming law nine years after they launched the initiative. After several false starts in Congress, the successful bill was sponsored by Senator William E. Borah. The bill authorized the creation of a 16-person organization, with a first-year budget of $25,640. Initially part of the Department of Commerce, the Children's Bureau was transferred to the Department of Labor in 1913. The law also called for the Bureau to be headed by a Chief, who would be a Presidential appointee, subject to Senate confirmation. The first Chief of the Children's Bureau was Julia Lathrop. Julia C. Lathrop, first Chief of the Children's Bureau.