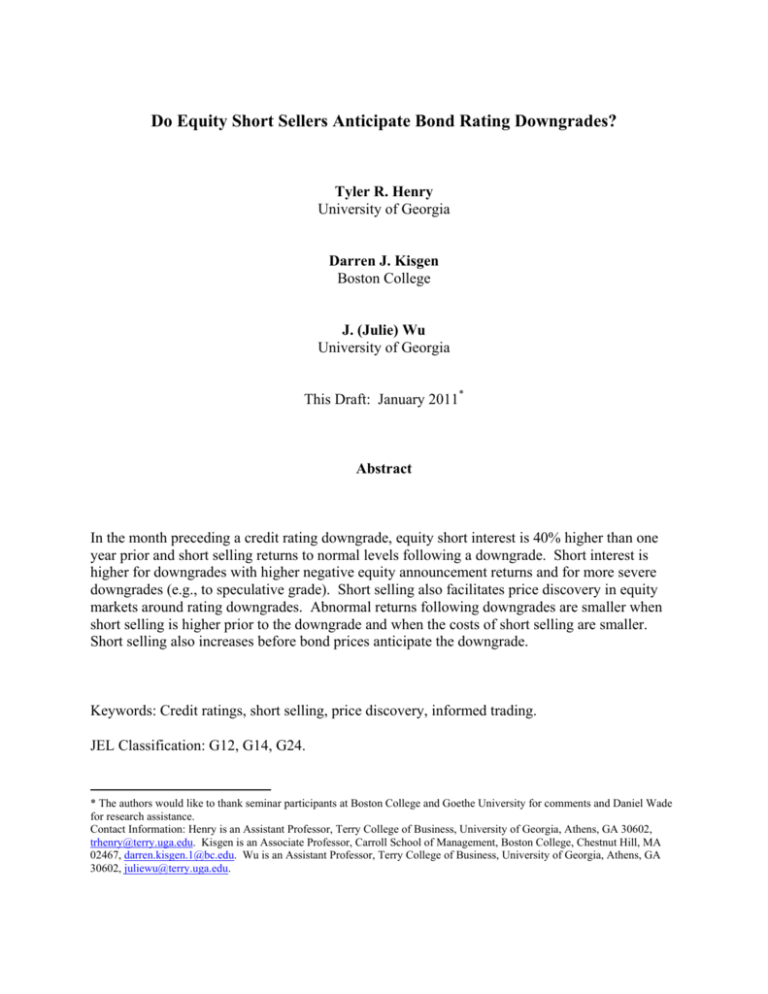

Do Equity Short Sellers Anticipate Bond Rating Downgrades?

advertisement