View Print version

advertisement

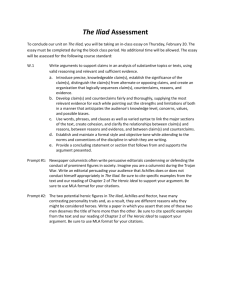

Homer’s epic tale of love, battle, and honor has never been more engaging than in this tour-deforce solo performance. Adapted from Robert Fagles’ revelatory and fresh translation of The Iliad, this play takes us on a sweeping and unforgettable journey through the Trojan War. This fierce and timeless story, starring two-time Tony Award®-winner Stephen Spinella, is absolutely not-to-be-missed! Glossary of Major Characters in The Iliad Greek Gods Zeus King of the Greek gods, husband of Hera. He is known for his erotic escapades; his illegitimate children include Helen, Athena, Apollo and Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, Dionysus, Helen, and the Muses. By Hera, he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Hebe, and Hephaestus. Hera Goddess of women and fertility, wife (and sister) of Zeus. Hera is often jealous and vengeful of his lovers. She hates the Trojans, especially Paris, and sides with the Greeks. Athena Greek virgin goddess of war (the discipline and art, as opposed to Ares, the violence and bloodlust), wisdom, and truth, patron goddess of Athens. She is thought to be the daughter of only Zeus, and to have sprung from his head full-grown and in full armor. She dislikes useless violence and prefers to use wisdom and compromise to solve conflict. She sides with the Greeks Aphrodite Greek goddess of love, beauty, and sexuality, as well as the unhappy and unfaithful wife of Hephaestus. She was created from the sea foam (aphros) that appeared when Cronus cut off Uranus’ genitals and threw them into the sea. She takes many lovers, especially Ares, god of war. She is especially fond of Paris, who declared her the most beautiful goddess, and sides with the Trojans. Apollo God of the sun, medicine, archery, and the arts. Apollo is the son of Zeus and Leto, and has a twin sister, the chaste huntress Artemis. He is best known for driving his sun chariot across the sky each day. He supports the Trojans in the war and often interferes on their behalf. Ares Ruthless god of war/ slaughter, courage, masculinity, and brother of Athena. Loves war itself, and is also associated with the ransacking of villages. Sometimes fights for Hector. Hephaestus God of smiths and metal working; husband of unfaithful Aphrodite. Son of Zeus and Hera; one account of his birth is that Hera, angry at Zeus’ infidelity, gave birth to Hephaestus by herself. By all accounts of his story, he is lame, but the cause varies (e.g., Hera enraged at his already grotesque body, hurls him from Olympus and he is permanently maimed by the fall; or Zeus flung him from Olympus for coming to his mother Hera’s rescue). In any case, he was raised by Thetis (mother of Achilles), and he crafts Achilles’ brilliant armor. Hermes God described as a guide and giant-killer, son of Zeus. He is Zeus’ messenger–swift, shrewd, and cunning. Escorts Priam when he goes to ask Achilles for Hector’s body. Poseidon God of the sea and younger brother of Zeus. Though he primarily interferes on the side of the Greeks, he backs down at Zeus’ behest and even steps in to save the Trojan Aeneas, who he knows is destined to be King of Troy. Thetis A sea goddess and the mother of Achilles. Zeus fell in love with her, but could not marry her due to a prophesy (her son is destined to be greater than his father) so he set her up with the mortal Peleus. She took care of Hephaestus when he was thrown from Olympus, and goes to him to ask him to make armor for Achilles. Greeks (Achaens) Achilles Son of Peleus and Thetis, commander of the Myrmidons, Achaen allies. He is the champion of the Greeks, but his rage is the source of much of the conflict in The Iliad. It was prophesized that Achilles would lead either a short, glorious life or a long, dull one. Agamemnon King of Mycenae, husband of Clytemenestra, brother to Menelaus, supreme commander of all Achaea’s armies. The conflict of The Iliad begins when he angers Apollo (who sends a plague to Achaea) by taking the daughter of one of his priests. When she is returned, on Achilles’ suggestion, Agamemnon insists on taking Achilles’ prize, Briseis, for his own. Atreus Father of Menelaus and Agamemnon. Briseis Captive and lover of Achilles. She is taken by Agamemnon when he is forced to give up Chryseis, causing Achilles to fly into a rage and refuse to take part in the fighting. Diomedes King of Argos. Along with Great Ajax, one of the strongest fighters for Achaea. Great Ajax Commander of the contingent from Salamis. A champion for the Achaean army second only to Achilles. Helen The daughter of Zeus and the wife of Menelaus. The Trojan War begins when Paris abducts her from Sparta after Aphrodite has promised her as a gift. In The Iliad she is self-loathing and regretful. Menelaus King of Mycenian Sparta, husband of Helen (stolen by Paris of Troy). Brother of Agamemnon, who is the king of Mycenae. Menoetius Father of Patroclus. Nestor A former Argonaut. He is old at the time of the Trojan War, in which his sons fight. He offers counsel to Agamemnon and Achilles, and leads troops, but does not fight himself. He is the oldest of all the chieftains. Odysseus King of Ithaca and protagonist of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey. Odysseus is known for his cunning; the Trojan Horse is his idea. Patroclus Achilles’ best friend who borrows his armor to fight in the war when Achilles will not. His death, at Hector’s hand, inspires Achilles to return to battle. Peleus Father of Achilles. His first marriage is to Antigone. When she commits suicide over false rumors of his infidelity, Peleus marries sea nymph Thetis, with whom he has Achilles. Thetis and Peleus become immortals by some accounts, by others, she abandons him. Trojans (Dardans) Aeneus Son of Anchises and Aphrodite; favorite of Apollo. When Aeneus fights for the Trojans in the Trojan War, his mother Aphrodite often comes to his rescue (though he is a good soldier). Andromache Hector’s wife. She asks him not to return to war on his brief visit home. Anchises Aphrodite’s mortal lover, with whom she fathered Aeneus. Anchises brags about being the lover of Aphrodite and Zeus strikes him with a thunderbolt. Aeneus saves his father by carrying him on his back and fleeing from the fires at the end of Trojan War. Astyanax Hector’s baby son, eventually killed at the hands of the Greeks. Cassandra Daughter of Priam. Apollo loved her and made her a prophet. When she rejected him he cursed this gift, and no one believes her visions. She is very beautiful and is the first to see Priam returning to Troy with Hector’s body. Hector Priam’s oldest son, Paris’s brother and Troy’s supreme commander. He kills Patroclus which spurs Achilles to return to war. Hecuba Priam’s wife and Hector’s mother. Paris Son of Priam and younger brother of Hector. A colossal coward. Legend has it that at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, Eris, a troublemaking god who was not invited, threw an apple into the party for “the most beautiful woman” there; Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite all claimed it. The women asked Zeus to decide, but wanting nothing to do with the decision, Zeus passed the task along to Paris. All the goddesses offered Paris gifts, but he chose Aphrodite who promised him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen. When Paris stole Helen from her husband Menelaus it began the Trojan War. Paris later kills the great warrior Achilles, by shooting an arrow through his heel from behind. Priam King of Troy, father of Hector and Paris. He goes to Achilles himself to request the body of Hector. Homer: The Iliad’s First Storyteller By Emilia LaPenta Homer’s name conjures images of a blind poet, wandering through ancient Greece, reciting his two brilliant epic poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey. But more than a person, Homer is an idea. The historical figure is a mystery to us—other than the poems, there is little evidence to support his existence and contradictions abound. Scholars have argued that many people were actually involved in writing The Iliad and The Odyssey. Some suggest Homer might have been a woman. He may have lived not long after the events of the Trojan War (1250-1240 B.C.E.), but others place him much later, in the eighth or seventh century B.C.E. Whoever he (or she or they) was, the spirit of Homer was part of the ancient Greek oral tradition: bards, usually blind, traveled from town to town, performing in public places and in royal courts. Stories were passed on for generations and memorized with the aid of a specific, repetitive structure. Improvisations around familiar story lines were common. In this way, he is also part of the tradition of storytellers, one that crosses cultures and endures throughout history. Homer, wrote Alexander Pope, “makes us hearers,” and his poems, read or performed, reveal the humanity behind often graphic war stories. His champions are not indestructible and his gods are not infallible. These achievements have had significant historical and philosophical impacts on the ancient Greeks and the contemporary world. Homer’s The Iliad was a pivotal part of classical education, as one of the masterpieces from the glorious days of Ancient Greece. Students at the Library of Alexandria in the third and second century verified, edited, and divided Homer’s work, creating documents that saved his texts from age and ruin. The Romans also embraced Homer thanks to Virgil who modeled the famous Aeneid on Homer’s poems. Prominent figures from Goethe, to Nietzsche, to Edgar Allen Poe were inspired and entranced by the epic poems in many facets: as a piece of art, an historical document, and as a product of ancient Greek culture. The story of war, and our complicated relationship to it, has proven to be one of the most timeless subjects of life and art and Homer, the proclaimed author of the ultimate war epic, a figure of mythic proportions. Summary of Action Leading Up to the Trojan War According to the popular myth, the Trojan War began when Paris, a prince of Troy, was made to judge which of three Greek goddesses, Athena, Hera, or Aphrodite, was the most beautiful. He awarded the prize to Aphrodite, and was rewarded with the hand of Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. Unfortunately, Helen was already married to the Greek king Menelaus. This didn’t stop Paris from kidnapping Helen and taking her to Troy as his wife, an act that prompted Greek forces under the command of Menelaus’ brother, Agamemnon, to declare war on Troy. But before the battle could be joined, the Greek army had to get to Troy, a task that required the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter to appease the gods. The arrival of the Greek army marked the beginning of a ten-year siege that finally ended in the sacking and burning of Troy. reprinted with permission from Seattle Repertory Theatre publications Storytelling through the Ages By Kathleen Burke and Emilia LaPenta From caves and campfires to halls of great kings and modern theaters, humans have told stories. Many of these stories are entertaining, but also practical. Some stories serve as historical accounts; others were used to cope with the unknown. While the mediums throughout the ages have changed, we have always had a need to record the touchstones of our cultures. Troubadours and Traveling Troupes In medieval Europe, minstrels (also called troubadours or bards) toured the land performing in inns, churches, courts, or wherever they could find an audience. They sang songs of war, love, heroism, and holiness, and became so popular that kings, lords and even bishops sought to have minstrels as part of their court. When a stronger written tradition emerged, these traveling performers became “the fool” of popular literature. In Italy, a tradition of traveling theater troupes performing as stock characters came to be known as commedia dell’arte, which was largely improvised. Commedia dell’arte is still practiced today, and the legends of the minstrel live on in today’s folk and music artists. Griots Griots are West African bards and are still an important part of many African communities. Some of a griot’s many roles include poet, praise-singer, and historian. Griots are often trusted with the important stories of a community, and hired to perform them on special occasions. Modern hip-hop culture is partly influenced by this traditional African occupation (see below). Biwa-hōshi In Japan before the early nineteenth century there were figures similar to the griot in Africa and the bard of Homer’s time called biwa- hōshi. The biwa- hōshi were itinerant musicians who primarily sang epic narratives about the samurai. They were usually blind and believed to be prophetic, an idea shared by the ancient Greeks (the blind can “see” another level of truth). Native American Storytelling Native Americans use stories to pass on the traditions of their culture. For the Cherokee of North Carolina, storytelling is a sacred ritual; before hearing one of the sacred stories, the listener needs to visit the medicine man to be fully prepared. The Sioux often tell stories of the relationship between humans and creation, to deepen respect of the native land. Early American Tall Tales Some of what we know about early United States leaders and famous figures is oral tradition; did, or did not, George Washington cut down the cherry tree? Folk tales and tall tales began around a fire where lumberjacks and other Americans gathered to share stories of Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill. Such characters from “fakelore” capture the expansionist spirit of the time. Hip-Hop: Storytelling Rap Hip-Hop is a subculture that was born in the United States and has roots in the African griot and the Jamaican dee-jay. Both traditions involve talking or chanting over some sort of musical accompaniment or rhythm. One of the most popular musical movements in the hip-hop culture is storytelling rap. Many storyteller rappers employ numerous literary techniques–from similes to double entendres–to make their work more nuanced and complex. Today’s Media Today, storytelling has come to take on a more personal, intimate form. People have begun to explore how their own journey fits into the fabric of culture through one-person shows, You-Tube videos, innovative podcasts like This American Life, and even the philosophical musings of a Facebook status. Solo performers like Nilaja Sun, Danny Hoch, and Sarah Jones continue the age-old tradition of theater written and performed by the individual for the community. Storytellers everywhere have access to media that allows them to tell their own story to an even broader audience. An Iliad rides to McCarter on the age-old wave of storytelling. The lone man imparting the tales of Achilles and Hector hearkens back to the minstrels singing songs of heroism and hard-won love, while An Iliad’s sly references to modern war give it the feel of a contemporary political blogger. An Iliad demonstrates that stories don’t fade with the fashions; this war story resonates as strongly as it did for the Greeks. A “Cast of One”: The History, Art and Nature of the One-Person Show by Paula T. Alekson In the world of the theatre, the one-man show is perhaps the closest thing to having it all, a supreme test of assurance and ability, of magnetism and charisma. The format is both seductive and frightening; there’s no one to play against, to lean on, to share the criticism. But, for an actor, the prize at the end of a successful solo performance in not only applause but also acclaim—unshared. — Enid Nemy, from “Four for the Season, Alone in the Spotlight", New York Times (October 5, 1984) The American one-person show found its roots in the “platform performances” of the late-nineteenth century, in which authors, public speakers, and actors “masquerading” as professional elocutionists gave readings or recitations from published works of literature to polite audiences for their cultivation and edification. These events were purposely held in nontheatrical venues as a way to distinguish them from theater entertainments (such as vaudeville), which, due to the long history of antitheatrical prejudice (i.e., a bias against or hostility toward the theater and those associated with it) were still regarded as immoral amusements created by sinful and degenerate individuals. The lecture, Lyceum, and Chautauqua circuits featured American platform personalities such as Edgar Allen Poe, Henry David Thoreau, Alexander Graham Bell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Daniel Webster, Anna Cora Mowatt and Charlotte Cushman. When Charles Dickens toured both Great Britain and America reading excerpts from his various works, he caused a sensation by embodying his numerous and diverse characters as he read. Mark Twain (Samuel L. Clemens) spent much of his nonwriting career appearing on the platform as lecturer and humorist, and he perfected a presentational technique which transformed his literature into performance texts. Lectures and readings eventually metamorphosed into one-person performances on the platform circuit as the focus of the performative material turned from literature to character sketches and monologues written expressly for performance. Eventually one-person showpieces began to appear on both the vaudeville and the legitimate stages, and sketches and monologues gave way to monodramas, or one-character plays. A surge in the number of one-person shows occurred in the American theater in the 1950’s and has never really decreased, owing not only to the popularity of the form, but also to its economical nature—a cast of one and, quite often, no set! One-person shows—or solo performances, as they are often called—of the latetwentieth century to the present are largely artistic vehicles designed to display actor virtuosity and stamina, to highlight an actor’s ability of impersonation (of either one character or a variety of characters), to present a theater-going audience to a larger-than-life historical (or sometimes living) figure, and/or as a means of intimate autobiographical exploration and expression. There are two modes for one-person shows: monologue and monopolylogue. A monologue features a single character speaking to a silent or unheard listener (most often the audience, who may be ignored or treated as observer, guest, confidant, or as a specific character). A monopolylogue features multiple characters, all performed by one actor; some monopolylogues feature dialogue in which the various characters talk to or converse with one another. There are many types of one-person shows, and some defy clear classification. The most straightforward forms are biographical or autobiographical in nature. A biographical oneperson play involves an actor directly impersonating or presenting his or her interpretation of the essence of a living or historical personage. Examples of this form are Mark Twain Tonight! written and performed by Hal Holbrook, William Luce’s portrait of Emily Dickinson, entitled The Belle of Amherst, which was originally performed by Julie Harris; Golda’s Balcony, in which Tovah Feldshuh first created William Gibson’s dramatic depiction of Golda Meir; and Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife in which Jefferson Mays created the role of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf and thirty-four other characters with whom she interacts (including the playwright). In an autobiographical one-person play, a writer/performer appears as him or herself and tells sometimes extremely intimate stories about his or her own life. Spalding Gray’s Swimming to Cambodia, Lisa Kron’s 2.5 Minute Ride, and Martin Moran’s The Tricky Part are representative of this form. Many contemporary solo performance pieces defy broad and clear categorization. For example, Anna Deavere Smith’s Fires in the Mirror and Twilight: Los Angeles 1992, utilize documentary material, such as personally recorded interviews and archival video recordings of public and private persons, which Smith weaves into a tapestry of monologues to tell the stories of and comment upon two dramatically explosive socio-historical events. Jane Wagner’s The Search for Intelligent Life in the Universe, written for and performed by Lily Tomlin, at first glance seems to be a series of largely unconnected, self-contained, whimsical character monologues, but the play slowly reveals itself as a satirical critique and outline of the Women’s Movement in the latter half of the twentieth century. Monopolyloguist Nilaja Sun’s No Child… draws from the playwright-performer’s true-to-life experience as a teaching artist in the Bronx to present a monodrama of Sun’s attempts to mount a production of Our Country’s Good with a group of disaffected high school students. In one scene of the play, Sun embodies at least seven characters in an amazingly animated conversation between a classroom of students, Sun, and their teacher. Regardless of their mode or form, one-person shows give the solo performer power, control, and complete responsibility over the work in performance. For the artist who is both writer and performer, there is absolute artistic freedom in the creative process and performance of his or her work. Perhaps one of the greatest reliefs for the solo actor is that he or she doesn’t have anyone depending upon him or her in the midst of a live performance, but therein lies the challenge, as he or she has no one but him or herself to depend upon—it is just the actor and the audience. It is a risky and exhilarating proposition for both sides of the theatrical equation. An Iliad Resource Guide Bibliography/Additional Sources Dalby, Andrew. Rediscovering Homer. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006. Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1942. Hedges, Chris. War is a Force that Gives Us Meaning. New York: Anchor Books, 2002. Kershaw, Stephen P. The Greek Myths. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007. Knox, Bernard. “Introduction.” The Iliad. Trans. Robert Fagles. London: Penguin Books, 1990. McCarty, Nick. Troy. London: Carlton, 2004. Manguel, Alberto. Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey: A Biography. London: Atlantic Books, 2007. O’Brien, Tim. The Things They Carried. New York: Broadway Books, 1990. Wood, Michael. In Search of the Trojan War. New York: New American Library, 1985. Other Translations of The Iliad Fitzgerald, Robert. The Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Lombardo, Stanley. The Iliad. Hackett Publishing Company, 1997. Storytelling http://www.rps.psu.edu/0205/keepers.html http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/minstrels001.html http://library.thinkquest.org/10949/fief/hientertain.html http://www.themiddleages.net/people_middle_ages.html http://www.commedia-dell-arte.com/ http://www.dellarte.com/dellarte.aspx?id=257 http://www.pbs.org/circleofstories/index.html http://www.ibiblio.org/storytelling/cherokee.html http://www.ancientnative.org/amd.php Emily Mann on An Iliad Dear Patrons, It gives me enormous pleasure to welcome you to An Iliad. Many of you are familiar with Homer’s The Iliad as a great work of literature, a book you read perhaps in high school or college. But this isn’t how Homer originally intended his epic story of the Trojan War to be received. A poet and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece, Homer performed his epic poems of heroes, history and myth. Decades before The Iliad was written down, Homer performed it for his audiences, captivating them for days as he recounted the tale of the Trojan War. When I first heard that Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare were writing a stage version of The Iliad meant to be performed by one storyteller, I was immediately intrigued. What better way to experience this thrilling tale than in its original form? And when I discovered that the stage adaptation was based on the world-renowned translation by Robert Fagles, I knew we had to produce it here at McCarter. In addition to being a noted Princeton professor and celebrated, award-winning translator, Robert Fagles was a very dear friend and it is a great pleasure to honor his remarkable translation through this production. Homer’s work celebrates heroism and honor, but it also exposes the brutality and folly of war. In An Iliad, Peterson and O’Hare connect the ancient past to the immediate present, drawing a direct line from Achilles and his men to the soldiers fighting in conflict zones around the world today. Just as the Greeks, on hearing Homer’s words, prayed for their soldiers’ safe return, so we pray for our own today. As long as man makes war, Homer’s poetry will ring with undeniable truth. Story for the Ages: An Iliad director Lisa Peterson shares why now is the best time to revisit the Trojan War By Ian Chant In books, on film, and now on the stage, the story of the Trojan War has been experiencing a renaissance in recent years. But what is it about a war that occurred thousands of years ago that remains so resonant today? An Iliad director Lisa Peterson supposes that there’s never really a wrong time to take a new look at the world’s oldest war story. “Somewhere in the world, people are always at war,” says Peterson. However, some times are more right than others to revisit the infamous conflict— particularly as it’s told through Homer’s classic tale, The Iliad. “This particular moment, I think, is unique,” Peterson says. “The Iliad begins nine years into a war that may have lost its underlying meaning.” It’s a situation that mirrors what many see in the current American military engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan. In the midst of the second Iraq war, Peterson found her own interest in dramatic responses to war sparked anew. As she was researching the topic and discussing it with colleagues, a friend made the argument that The Iliad was not a poem but a dramatic work. “It was a remnant of the oral tradition, it was an out-loud story; it was never intended to be something that you just read on paper. And I was really interested in that,” says Peterson. “I had studied The Iliad in college, but… I had never thought of it as a play, and I don’t think most people do.” Peterson was also intrigued by the opportunity to put a unique theatrical spin on a literary classic. After taking a long hiatus from helming the adaptations that marked her early career as a director, she was eager to return to adapting work, though not in a traditional manner. “I wanted to work on something as an adapter, and I was really interested in working directly with an actor instead of with a writer,” Peterson says. “I was interested in the idea of Homer as a traveling storyteller, as opposed to someone who sits and writes, and so it made more sense to go to an actor friend.” Peterson began collaborating on the work with friend and performer Denis O’Hare, initiating a multi-year process. Last spring, An Iliad premiered at Seattle Rep. While their original idea was an improvisational piece that would change slightly with every performance, “It did end up getting written down and codified…and now it is a script, but we are still trying to capture that sensation that he’s making it up on the spot,” Peterson says. “We’re trying to create the kind of feeling that might have been in the room thousands of years ago when Homer was telling the story.” Instilling that sense of awe at the spoken word in a modern audience is no small order. Peterson and O’Hare’s adaptation emphasizes the wide-ranging appeal of the tale and of storytelling, making An Iliad a bridge of sorts between the ancient and the modern. “We are imagining that our poet…has been around for millennia. He was there during the war, and he is doomed to walk the earth and tell his story. And over the years, he has adapted, always, to be wherever he happens to be.” As the development process on An Iliad moves ahead, the original continues to surprise Peterson. “Almost every day I find something…that I feel like I’ve never read,” Peterson says. But not every surprise can be brought to the stage. In crafting a 90-minute one-person show from an epic poem, choosing what aspects of the story to explore can be difficult. Ultimately, An Iliad focuses on exploring the source material’s meditations on the nature of war. “We dug until we found the core of the story,” Peterson says, “and for us that core is the conflict between two great warriors, Hector and Achilles.” Originally Published in Seattle Repertory Theatre Magazine, reprinted with permission. Who’s Who Stephen Spinella (Poet) Broadway: Spring Awakening, Our Town, James Joyce’s The Dead (Drama Desk Award, Outer Critics Award, Tony Nomination), Electra, A View from the Bridge, Angels in America: Millennium Approaches (Tony and Drama Desk Awards, Featured Actor), Angels in America: Perestroika (Tony and Drama Desk Awards, Leading Actor). OffBroadway: Svejk (TFANA), The Seagull (NYSF in the park, with Meryl Streep), Elle, A Question of Mercy (NY Theatre Workshop), Troilus and Cressida (NYSF in the park, Bayfield Award), Love! Valour! Compassion! (Manhattan Theatre Club, Obie Award), The Illusion (NY Theatre Workshop). Regional: The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism with a Key to the Scriptures (The Guthrie Theatre), Stuff Happens (Mark Taper Forum), Travesties (Williamstown), Electra (McCarter Theatre). Film: And the Band Played On, Faithful, Virtuosity, Love! Valour! Compassion!, Great Expectations, The Jackal, The Unknown Cyclist, Ravenous, Cradle Will Rock, Bubble Boy, Connie and Carla, House of D, And Then Came Love, Milk, Rubber. Television: The Education of Max Bickford, 24, Desperate Housewives, Heroes, Grey’s Anatomy, Will and Grace, Alias, Ed, Law and Order, Law and Order: SVU, Frasier, Nip/Tuck, Everwood, Huff, Without A Trace, ER, Big Love, Numb3rs, The Mentalist. Brian Ellingsen (Musician) New York City based double bassist Brian Ellingsen performs a wide range of styles from classical to cross media experimental. As a soloist he has placed in competitions such as the van Rooy Competition, the Paranov Concerto Competition, and the 2009 International Society of Bassists Competition. Brian has also appeared with the New York Chamber Soloists, Fifth House Ensemble, NOW Ensemble, Transit, and performed as principle of the Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra, under Pierre Boulez. Recently, Brian was accepted as a fellow with Ensemble ACJW. As an advocate for experimental music, Brian has collaborated with visual artists to bring their work to life through improvisations. Brian has also given many solo recitals, performing new works from today’s rising composers, in addition to his own improvisations. Calendar of Events Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday October 20 19 7:30 pm 21 22 23 7:30 pm 8:00 pm 3:00 pm Opening Night 8:00 pm 29 30 7:30 pm 8:00 pm 3:00 pm 7:30 pm 24 25 26 2:00 pm 7:30 pm Dialogue on Drama Performance PostPerformance Discussions 31 November 2:00 pm Pre-show Halloween Bash 7:30 pm 27 1 2 3 7:30 pm Dinner & Theater Saturday 28 Pride Night Party After Hours Party 4 5 6 7:30 pm 8:00 pm 3:00 pm 8:00 pm ASL Interpreted + Audio Described Performance 8:00 pm 7 2:00 pm CORE CURRICULUM STANDARDS According to the NJ Department of Education, “experience with and knowledge of the arts is a vital part of a complete education.” Our production of An Iliad and the activities outlined in this guide are designed to enrich your students’ education by addressing the following specific Core Curriculum Content Standards for Visual and Performing Arts: 1.1 The Creative Process: All students will demonstrate an understanding of the elements and principles that govern the creation of works of art in dance, music, theatre, and visual art. 1.2 History of the Arts and Culture: All students will understand the role, development, and influence of the arts throughout history and across cultures. 1.3 Performance: All students will synthesize those skills, media, methods, and technologies appropriate to creating, performing, and/or presenting works of art in dance, music, theatre, and visual art. 1.4 Aesthetic Responses & Critique Methodologies: All students will demonstrate and apply an understanding of arts philosophies, judgment, and analysis to works of art in dance, music, theater, and visual art. Viewing An Iliad and then participating in the pre- and post-show discussions and activities suggested in this audience guide will also address the following Core Curriculum Content Standards in Language Arts Literacy. 3.1 Reading: All students will understand and apply the knowledge of sounds, letters, and words in written English to become independent and fluent readers, and will read a variety of materials and texts with fluency and comprehension. 3.2 Writing: All students will write in clear, concise, organized language that varies in content and form for different audiences and purposes. 3.3 Speaking: All students will speak in clear, concise, organized language that varies in content and form for different audiences and purposes. 3.4 Listening: All students will listen actively to information from a variety of sources in a variety of situations. 3.5 Viewing and Media Literacy: All students will access, view, evaluate, and respond to print, non-print, and electronic texts and resources. In addition, the production of An Iliad as well as the audience guide activities will help to fulfill the following Social Studies Core Curriculum Standard: 6.2 World History/Global Studies: All students will acquire the knowledge and skills to think analytically and systematically about how past interactions of people, cultures, and the environment affect issues across time and cultures. Such knowledge and skills enable students to make informed decisions as socially and ethically responsible world citizens in the 21st century. PRE-SHOW PREPARATION, QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION, AND ACTIVITIES Note to Educators: Use the following assignments, questions, and activities to introduce your students to AN ILIAD and its intellectual and artistic origins, context, and themes, as well as to engage their imaginations and creativity before they see the production. 1. AN ILIAD: WEB SITE BASICS. Share the various articles and information found on McCarter's An Iliad Web Site with your students—preferably by reading them aloud as a class or in small groups—to provide an historical and creative context for Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare’s creative, contemporary adaptation of Homer’s epic poem. 2. EXPLORING HOMER’S ILIAD BEFORE A PERFORMANCE OF AN ILIAD. Homer’s Iliad stands at the beginning of the Western literary tradition, as well as at the center of a classical education. The 15,693 lines of hexameter verse is often referred to as “the first book,” although it was originally composed more than 2,700 years ago as an oral narrative poem—before the ancient Greeks even developed an alphabet—and intended for live recitation/performance. Lisa Peterson and Denis O'Hare's adaption An Iliad is based upon the Robert Fagles' translation of Homer (published by Penguin, 1990). Peterson, who also directs this production, was in midst of researching war plays as an artistic response to the protracted American wars with Iraq and Afghanistan in 2005, when The Iliad was suggested to her. She fell upon Fagles' translation and "fell in love”; she would get together with her collaborator, friend and performer O'Hare to read it aloud to one another. An Iliad focuses Homer's sprawling, 1,000-warrior Trojan War epic on the conflict of the War's two primary heroic opponents, Achilles and Hector, and includes lyrical passages largely from Books 1, 6, 16, 18, 22, and 24 of Fagles' translation. Below are two different methods of having your students experience the text of AN ILIAD through recitation of Homer’s immortal war poem in translation. Book One Bardship Have your students experience the nature of oral recitation and the vividness of Homer’s storytelling by reading aloud to one another from Book 1 of the Iliad by Homer, preferably Fagles' translation (Penguin Books, 1990). Remind them that Homer's poem was originally composed for oral transmission, and that in Ancient Greece professional singing performers (aoidoi, then rhapsodes) participated in competitions for prizes at religious/civic festivals. Although students needn't sing their assigned passages, encourage them to present them as lively and vividly as possible by engaging in the narrative and enacting the more dramatic dialogical passages. Ask students to discuss the joys and challenges of reading/reciting the Iliad as translated by Fagles. Engage students in a discussion of the story and themes of Homer's Iliad, Book 1. [Other fine and widely accessible translations include Robert Fitzgerald's (Anchor Books, 1974, 1989) and Richard Lattimore's The Iliad of Homer (University of Chicago, 1967), which may be available in your school's or community’s (public) library.] Battle of the Bards; or Dueling Translations Have your students experience the nature of oral recitation, the vividness of Homer’s storytelling and the art and craft of the translator by having them prepare for a bardic competition. The title of “Top Bard” will be given to the student-bard judged (by teacher and class) to have presented/performed the most lively, engaging and dramatic recitation of the climactic meeting of Achilles and Hector in Book 22 of Homer’s Iliad. Teachers can draw from the following translations (two are linked, the others may be may be available in your school’s or community’s (public) library): Robert Fagles, The Iliad (Penguin Books, 1990)—Lines 363-397. Robert Fitzgerald, The Iliad (Anchor Books, 1974)—Lines 364-400. Richard Lattimore, The Iliad of Homer (University of Chicago, 1967)—Lines 306336. This text can also be accessed via Northwestern University’s The Chicago Homer (web site): http://digital.library.northwestern.edu/homer/html/application.html Alexander Pope (1899)—Pages 398-399; lines not numbered. Start: Fierce, at the word, his weighty sword he drew,” End: Thee birds shall mangle, and the gods devour. Ask students to discuss the joys and challenges of reading/reciting the Iliad, as well as the joys and challenges of each different translation. Using secret balloting, have students select their favorite bardic performance. When voting, ask them to indicate what made the performance their favorite. When announcing the winner, read the comments commending the winning bard’s performance. Ask students to discuss the qualities of an engaging performance. If possible, crown the winning bard with laurel, in the Greek style! 3. IN CONTEXT: HOMER AND HIS ILIAD. To prepare your students for An Iliad and to deepen their level of understanding of the mythos of Homer and his mythological "poem of Ilium" have them research, either in groups or individually, the following topics: Homer and the "Homeric Question" Greek hero cults and Homereia Aoidoi and rhapsodes Troy The Gods Aphrodite Apollo Ares Athena Hephaestus Hera Hermes Thetis Zeus The Greeks/Achaeans Achilles Agamemnon Helen Menelaus Nestor Odyssesus Patroclus The Trojans Andromache Astyanax Cassandra Hector Paris Priam Have students teach one another about their individual or group topics via oral and illustrated (i.e., posters or PowerPoint) reports. Following the presentations ask your students to reflect upon their research process and discoveries. 4. GOING SOLO ON THE STAGE: AN EXPLORATION OF ONE-PERSON SHOWS. To prepare your students for An Iliad and deepen their level of understanding and appreciation of the one-person show tradition, familiarize them with a variety of solo performances pieces that they can view (and perhaps read), analyze, and discuss. First, utilize the brief article “A ‘Cast of One’: The History, Art, and Nature of the One-Person Show” found in this audience guide as a jumping-off point for your group exploration. Then, compare and contrast two or three of the following plays (most titles are available both in print and on VHS and/or DVD; a few may be available at your school's or local public library): The Belle of Amherst, William Luce Mark Twain Tonight!, Hal Holbrook Swimming to Cambodia, Spalding Gray Monster in a Box, Spalding Gray Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn, Anna Deavere Smith Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, Anna Deavere Smith Elaine Stritch At Liberty, Elaine Stritch (includes adult content /language) The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe, Jane Wagner (Direct from Broadway:) Whoopi Goldberg, Whoopi Goldberg Following each individual viewing: o Have students journal (free write) a personal response to the work of art. o Then ask them to journal about what they noticed about the work or where they found meaning (e.g. ask them to indicate what they found stimulating, surprising, evocative, memorable, touching, challenging, compelling, delightful, different, unique, or meaningful) in both play and performance. o Ask them to share their thoughts in an open discussion. Continuing the discussion: o Ask your students to identify the mode and form of each oneperson show they view. o Ask them if their viewing of the work of art gave them any insights into the pleasures and challenges of the one-person show form? o Have students consider if the story of the play is suited only to a solo-performance format. In other words, could they conceive of the play’s story in a more conventionally dramatic or theatrically expanded form (e.g., telling the story through the interaction of multiple characters, utilizing several actors to tell the story, using dialogue instead of monologue)? How would a different format change the theatrical experience for both actor and audience? o If students have the opportunity to view more than a single oneperson show, ask them to compare and contrast the plays, the performers and performance styles. POST-SHOW QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION AND ACTIVITIES Note to Educators: Use the following assignments, questions, and activities to have students evaluate their experience of the performance of AN ILIAD, as well as to encourage their own imaginative and artistic projects through further exploration of the play in production. Consider also that some of the pre-show activities might enhance your students’ experience following the performance. 1. AN ILIAD: PERFORMANCE REFLECTION AND DISCUSSION. Following their attendance at the performance of An Iliad, ask your students to reflect on the questions below. You might choose to have them answer each individually or you may divide students into groups for round-table discussions. Have them consider each question, record their answers and then share their responses with the rest of the class. QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR STUDENTS ABOUT THE PLAY IN PRODUCTION a. What was your overall reaction to An Iliad? Did you find the production compelling? Stimulating? Intriguing? Challenging? Memorable? Confusing? Evocative? Unique? Delightful? Meaningful? Explain your reactions. b. Did experiencing the play in performance heighten your awareness, understanding of, or connection to the ancient story of the Iliad and its themes? What themes or ideas were made even more apparent and/or significant in production/performance? Explain your responses. c. What did you think of actor Stephen Spinella in the role of the Poet? What was the nature or quality of his performance? Can you describe the strengths of his work as storyteller and actor? Was there anything that surprised you in his performance? d. Did Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare’s adaptation effectively tell the story of Homer’s Iliad and its characters? Did any one moment or part of the story stand out to you in particular? Which moment or part was it and why did you find it outstanding? e. What overall effect did Peterson and O’Hara’s intertwining narrative of the storyteller “Poet” and the story he tells have on you? Did you find this to be an effective and compelling way to tell the story of war then and now? f. Why do you think Peterson and O’Hare envisioned a “one-man” Iliad, that is, why did they choose to tell the Homer’s story in this way? What are the merits/advantages of an Iliad as a solo-performance piece? Could you imagine a multi-character Iliad? What would be the merits/advantages of a multi-character stage version of Homer’s Iliad? What would be the challenges/disadvantages? QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR STUDENTS ABOUT THE CHARACTERS a. Did you personally identify with Poet in An Iliad or with any of the characters in the story of the Trojan War? Who? Why? b. What memorable qualities or character traits were revealed by the action and speech of the Poet? Explain your ideas. c. In what ways did the Poet reveal the themes of the play? Explain your responses. d. What was the Poet’s overall attitude toward the story he is fated to tell? Do you think his attitude has changed by the play’s end? If you think it has changed, what is his new attitude? What do you think this change in his attitude—or a lack of change—indicates? QUESTIONS TO ASK YOUR STUDENTS ABOUT THE STYLE AND DESIGN OF THE PRODUCTION a. Was there a moment in An Iliad that was so compelling or intriguing that it remains with you in your mind’s eye? Write a vivid description of that moment. As you write your description, pretend that you are writing about the moment for someone who was unable to experience the performance. b. Did the style and design elements of the production enhance the performance? Did anything specifically stand out to you? Explain your reactions. c. Did the overall production style and design reflect the central themes of the story of An Iliad? Explain your response. d. What did you notice about the set design? Did it provide an appropriate and/or evocative setting/location for An Iliad? How and why, or why not? e. What mood or atmosphere did the lighting design establish or achieve? Explain your experience. f. What did you notice about the costume worn by the “Poet.” What do you think were the artistic and practical decisions that went into the conception of the costume? g. Did you find that the music in the production, composed by Mark Bennett and performed by double bassist Brian Ellingsen (“The Muses”), effectively served in the telling of the story of An Iliad? If so, what did the music and “The Muses” bring to the production? 2. ADDITIONAL POST-SHOW QUESTIONS AND DISCUSSION POINTS FOR AN ILIAD. Comparing Homer’s Iliad and An Iliad: A War Poem Retold Homer’s Iliad is an epic poem that narrates the story of the Trojan War and, as the first line of the poem indicates, “the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles.” Although the tale that Homer tells is replete with vivid and disturbing details of the horror, violence, suffering and misery of war, it also, as historian Bernard Knox notes in his introduction to Robert Fagles’ translation, “is a poem that celebrates the heroic values war imposes on its votaries,” and the glory and excitement of battle. Director and co-author of An Iliad, Lisa Peterson conceived of the notion of taking the world’s greatest war poem and finding a way to adapt it into a play that would “demand a public conversation” on the subject of war. She and co-author Denis O’Hare entitled their adaptation An Iliad to suggest that theirs is not THE Iliad, but simply one telling of it. Ask your students to contemplate Peterson and O’Hare’s adaptation and reimagining of Homer’s war poem as a play and then engage them in a “public discussion” based upon the following questions: In the process of experiencing An Iliad, did it strike you as a work of political art critical of war? How would you characterize An Iliad’s point of view on war? What parallels, if any, did your brain construct between the Trojan War and the U.S. and Iraq and Afghanistan Wars (or any other war) as you experienced An Iliad in performance? Do you find the play and production to be an effective work of political art? Why or why not? Did you find An Iliad to be emotionally as well as intellectually engaging? What did you find to be most engaged by the performance: your heart, your brain, or your spirit? Explain your answers. One the Other Hand: “More About Homer…” An Iliad director and co-author, Lisa Peterson, has also said the following about her play: “This Iliad is more about Homer than the Trojan War.” 3. Ask your students to consider what Peterson might have meant by that comment. Suggestion: Have them consider the Poet in the production of An Iliad to be Homer himself. What is it that the Poet seems to want? Why does he tell the story? A ONE-MAN ILIAD. A solo-play such as An Iliad requires what theater professionals refer to as a “tour de force” performer, that is, an actor with great talent, skill, stamina, virtuosity, and psychological strength or confidence. It is the performer’s ultimate challenge, and it is reasonable to say that not just any actor could take on such a role. Certainly Stephen Spinella is not just any ordinary actor. Spinella is a star of stage, screen, and television, and has won two Tony Awards and three Drama Desk Awards for his acclaimed work in Broadway plays and musicals including Angels in America: Milienium Approaches, Angels in America: Perestroika, and James Joyces’s The Dead. Ask your students to reflect upon Stephen Spinella’s performance in An Iliad and the one-person show form and its challenges using the following questions: 4. What did you find compelling, exciting, surprising, confounding, or worth noting about Stephen Spinella’s performance in An Iliad? What one moment of Spinella’s performance stands out foremost in your mind when you think of An Iliad? Describe that moment in detail and explain why you think it remains foremost in your thoughts. What were the pleasures of watching Spinella embody the Poet and the other characters in the play? Was there anything that didn’t work for you in the performance of the piece? Explain your response. What in the nature of An Iliad (e.g., narrative, theme, characters, structure) recommends it as or requires that it be a solo performance piece? Explain your answer. What would be lost theatrically or thematically if An Iliad were expanded into a play for multiple characters, if anything? Explain your response. AN ILIAD: THE REVIEW. Have your students take on the role of theater critic by writing a review of the McCarter Theatre production of An Iliad. A theater critic or reviewer is essentially a “professional audience member,” whose job is to provide reportage of a play’s production and performance through active and descriptive language for a target audience of readers (e.g., their peers, their community, or those interested in the arts). Critics/reviewers analyze the theatrical event to provide a clearer understanding of the artistic ambitions and intentions of a play and its production; reviewers often ask themselves, “What is the playwright and this production attempting to do?” Finally, the critic offers personal judgment as to whether the artistic intentions of a production were achieved, effective and worthwhile. Things to consider before writing: Theater critics/reviewers should always back up their opinions with reasons, evidence and details. The elements of production that can be discussed in a theatrical review are the play text or script (and its themes, plot, characters, etc.), scenic elements, costumes, lighting, sound, music, acting and direction (i.e., how all of these elements are put together). [See the Theater Reviewer’s Checklist.] Educators may want to provide their students with sample theater reviews from a variety of newspapers. Encourage your students to submit their reviews to the school newspaper for publication. Students may also post their reviews on McCarter’s web site by visiting McCarter Blog. Select “Citizen Responses” under “Categories” on the left side of the web page, and scroll down to the An Iliad entry to post any reviews. 5. BLOG ALL ABOUT IT!: AN ILIAD. McCarter is very interested in carrying on the conversation about An Iliad with you and your students after you’ve left the theater. If you are interested in having them personally reflect upon their experience of the play in performance, but are not interested in the more formal assignment of review writing, have them instead post a post-show comment on the McCarter Theatre Blog. To access the blog, click on this link McCarter Blog , then select “Citizen Responses” under “Categories” on the left side of the web page, and scroll down to the An Iliad entry to find a place to post an inquiry or comment. [For structured responses, consider the following prompt: What expectations did you bring with you to An Iliad and were your expectations met, not met, or exceeded by the performance?] See you on the blog!