The Odyssey

advertisement

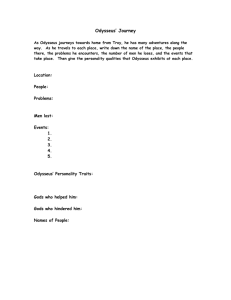

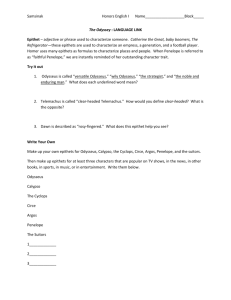

The Odyssey By the epic poet, Homer 1. Polyphemous The Cyclops 2. Aeolus and The Bag of Winds 3. Circe The Sorceress 4. Hades and Teiresias 5. Scylla and Charybdis 6. The Sun God’s Cattle 7. Calypso’s Captivity 8. Poseidon’s Revenge 9. Telemachus and Penelope 1 1. Polyphemous The Cyclops I am Odysseus, sacker of cities, King of Ithaka. The whole world knows of my tricks, how I convinced Achilles to sail on Troy, and my fame is known to the Gods. Let me tell you of the disastrous voyage Zeus and Poseidon inflicted on me on our way back from Troy. After ten long years the Trojans had fallen into my trap and dragged the Wooden Horse into the citadel, and I brought doom and slaughter to the city. Our ships full of Trojan gold and wine, we set sail. Zeus, who controls the clouds, sent my fleet a terrible gale from the North. He covered land and sea with a canopy of cloud; darkness swept down on us from the sky. For nine days I was chased by those accursed winds across the teeming seas. With the fear of death on us, we rowed the ships to land with all our might. And so we came to the land of the Cyclops, a fierce, lawless people who live in hollow caves in the mountain heights. I had an instant foreboding that we were going to find ourselves face to face with some barbarous being of colossal strength and ferocity, uncivilised and unprincipled. It took us very little time to reach a cave, but we did not find its owner at home. We lit a fire, helped ourselves to some food, and at last the owner of the cave came up, shepherding his flock. He picked up a huge stone, with which he closed the entrance. It was a mighty slab, of monstrous size. Then he spied us: ‘’Strangers!’ he bellowed. ‘And who are you? Where do you come from over the watery ways? Are you roving pirates, who risk their lives to ruin other people?’ Our hearts sank. The booming voice and the very sight of the monster filled us with panic. ‘We are Greeks,’ I said, ‘on our way back from Troy, sacking the great city and destroying its armies, driven astray across the sea. Remember your duty to the Gods; Zeus is the champion of guests: guests are sacred to him, and he goes alongside them’. And this is what he said: ‘Stranger, you must be a fool, to order me to fear the Gods. We Cyclops care nothing for Zeus, nor for the rest of the Gods, since we are much stronger than they are. I would never spare you for the fear of Zeus.’ He seized a couple of men, dashed their heads against the floor, and their brains ran out on the ground and soaked the earth. Limb by limb he tore them to pieces to make his meal, which he devoured like a mountain lion, leaving nothing, nor flesh, marrow, nor bones, while we were completely helpless. When the Cyclops had filled his great belly up with this meal of human flesh, he stretched himself out for sleep among his flocks inside the cave. On first thoughts I planned to summon my courage, draw my sharp sword, and stab him in the heart. But on second thoughts, I realised we would seal our own fate as well as his, because we would have found it impossible to push aside the huge rock with which he had closed the great mouth of the cave. So with sighs and groans we waited for the light of day. When dawn approached, the Cyclops once more snatched up two of my men and prepared his terrible meal. When he had eaten, he turned his flocks out of the cave, then replacing the great doorstone without effort. I was left, with murder in my heart, scheming to find the best plan I could think of. Lying in the cave the Cyclops had a huge staff, though to us it looked more like the mast of some great ship. I sharpened it to a point, then I hardened it in the fire, and finally I carefully hid it under the dung. I then told my company to cast lots for the dangerous task of helping me to lift the pole and twist it in the Cyclop’s eye when he was sound asleep. 2 Evening came, and with it the Cyclops, once more snatching two of us and preparing his supper. Then with a wood bowl of my dark wine in my hands I went up to him and said: ‘Here, Cyclops, have some wine to wash down your meal of human flesh”. The Cyclops took the wine and drank it up. And he called for another bowlful: ‘Give me more, and tell me your name, for this wine is a drop of the nectar and ambrosia the Gods drink’. I handed him another bowlful; three times I filled it for him, and three times the fool drained the bowl to the dregs. At last, when the wine had fuddled his wits, I addressed him: ‘Cyclops, you ask me my name. I’ll tell it to you: my name is Nobody; that is what I am called by my mother and father and by all my friends.’ The Cyclops answered me from his cruel heart. ‘Of all his company I will eat Nobody last, and the rest before him.’ He toppled over and fell face upwards on the floor, his great neck twisted over on one side, and all-­‐compelling sleep overpowered him. In his drunken stupor he vomited, and a stream of wine mixed with the morsels of men’s flesh poured from his throat. I went at once and thrust our pole deep under the ashes of the fire to make it hot, and meanwhile gave a word of encouragement to all my men, to make sure none would hold back through fear. Seizing the pole, we twisted it in his eye till the blood boiled up round the burning wood. The scorching heat singed his lids, while his eyeball blazed and hissed and crackled in the flame. He gave a dreadful roar, echoing round the cave, pulled the stake from his eye, streaming with blood, and raised a great shout to the other Cyclops who lived in the other caves. Hearing his screams they shouted, ‘What on earth is wrong with you, Polyphemous? Why must you disturb our night and spoil our sleep? Is someone trying by treachery or violence to kill you?’ Out of the cave came mighty Polyphemous’s reply: ‘It is Nobody’s treachery and violence that is doing me to death.’ ‘Well then’ came the reply, ‘if nobody is assaulting you, you cannot be helped. All you can do is pray to your father, the God Poseidon.’ And off they went, while I laughed at my cunning trick. The Cyclops, still groaning in the agony of pain, groped about with his hands and pushed the rock away from the mouth of the cave, in the doorway stretching out both arms in the hope of catching us escaping. What a fool he must have thought me! Meanwhile I was cudgelling my brains, trying to hit on some way to save myself and my men: we were in mortal peril. This was the plan that eventually seemed best: I lashed the rams of the flock in threes, and we lay upside down, with patience in our hearts. Tortured and in terrible agony, Polyphemous passed his hands over the animals as they left the cave for the pastures, but never noticed that my men were under the chests of the rams. As soon as we were out, we hurried to our ship. But before we were out of earshot, I shouted derisive words at Polyphemous: ‘Cyclops! Your crimes were bound to catch up with you, you brute, who did not shrink from devouring your guests! Now Zeus and all the other gods have paid you out.’ My words so enraged the Cyclops that he tore a great pinnacle of rock and hurled it at us. The rock fell just short of our ship. Seizing a long pole, I pushed our ship off, commanding my crew to use their oars and save us from disaster. When at a distance I was about to shout something else to the Cyclops, but my men called out, trying to pacify me: ‘Why do you want to provoke this savage? We’re still within his range!’ But my temper was up; their words did not dissuade me and in my rage I shouted back at him once more: ‘Cyclops! If anyone asks you how you were blinded, tell him your eye was put out by Odysseus, sacker of cities, King of Ithaka!’ At this the Cyclops lifted his hands to the starry heaven and prayed to the God Poseidon: ‘Hear me, Poseidon. I am yours indeed and you claim me as your son. Grant that Odysseus, sacker of cities, may never reach his home in Ithaka, or let him come late, in wretched plight, having lost all his comrades, and let him find trouble in his home’. So he prayed, and the Sea God heard his prayer. Once again the Cyclops picked up a boulder – bigger, by far, this time – and hurled it with such tremendous force that it only just missed the rudder of our ship. The water heaved up at it plunged into the sea, but the wave that it raised carried us on. So we left the island of the Cyclops and sailed on with heavy hearts, grieving for our dear friends but glad at our own escape from death. 3 2. Aeolus and The Bag of Winds We came next to the floating island of Aeolia, the home of Aeolus who is a favourite of the immortal gods. All round this island there runs an unbroken wall of bronze, and below it sheer cliffs rise from the sea. To this magnificent palace we now came. For a whole month Aeolus entertained me and questioned me on everything – how I pretended to be mad to avoid fighting at Troy for the Greeks, and was cursed by Zeus’ wrath; how I persuaded Achilles to fight at Troy with the lure of immortal glory; how I tricked the Trojans with the victory gift of the Trojan horse, and slaughtered the city; how I tricked Polyphemous the Cyclops and blinded him, and how Poseidon cursed me as I boasted. When it came to my turn and I asked him if I might continue my journey and count on his help, he gave it willingly. He made arrangements for my journey and presented me with a leather bag, made from an ox-­‐skin, in which he had imprisoned the boisterous energies of all the winds. Zeus had put him in charge of the winds, with power to calm or rouse each of them at will. This bag he stowed in the hold of my ship, securing it tightly with a silver wire to prevent the slightest leak. Then he called for a breeze from the West to blow my ships and their crews across the sea. But his efforts were doomed to failure, for we came to grief, through our own senseless stupidity. For nine days and nights we sailed on; an on the tenth we were already in sight of our homeland, and had even come near enough to see people tending their fires, when I fell fast asleep. I was utterly exhausted, for in my anxiety to speed our journey home I had handled my ship myself without a break, giving it to no one else. The crew began to discuss matters amongst themselves, and the word went round that I was bringing home a fortune in gold and silver which Aeolus had given to me. And this is what they said as they exchanged glances: ‘It’s not fair! What a captain we have, valued wherever he goes and welcomed in every port! Back he comes from Troy with a splendid haul of plunder, though we who have gone through every bit as far come home with empty hands. Come on, let’s find out and see how much gold and silver is hidden in that bag.’ After talk like this the evil advice prevailed. They undid the bag, the winds all rushed out, and in an instant the tempest was on them, carrying them headlong out to sea, in tears, away from their homeland. When I awoke my spirit failed me. I debated with myself whether to jump overboard and drown or stay amongst the living and quietly endure. I stayed and endured. Covering my head with my cloak, I lay where I was in the ship. So all my ships, with their distraught crews, were driven back to the island of Aeolus. We disembarked and collected water, and the men straightaway had a quick meal by the ships. But as soon as we had had something to eat and drink I took a messenger and one of my comrades to accompany me and set out for the palace of Aeolus. They were astounded at the sight of us. ‘Odysseus?’ they exclaimed. ‘How do you come to be here? What evil power has dealt you this blow? We did our best to help you on your way home to Ithaka or any port you might choose.’ I replied sorrowfully, ‘An untrustworthy crew and a fatal sleep were my downfall. Put things right for me, my friends. You easily could.’ With these words I appealed to them. 4 They remained silent. Then Aeolus answered: ‘Get off this island immediately! The world holds no one more cursed than you, and it is not right to entertain and equip a man hated by the Gods. Your return shows they hate you! Get out!’ He dismissed me from the palace, causing me deep distress. We left the island and resumed our journey in a state of gloom, and the heart was taken out of my men by the wearisome rowing. But it was our own stupidity that had deprived us of the wind. For six days and six nights we sailed on, and on the seventh we came to the land of the Laestrygonians. The captains of my fleet all steered their ships straight into the harbour and the sheltered water between steep cliffs and jutting headlands, so that only a narrow channel was in between. But I did not follow them. Instead I brought my ship to rest outside the harbour and fastened her to a rock. I then climbed the headland to get a view from the top. But no fields or cattle were visible; all we saw was a whisp of smoke rising up from the countryside. So I sent a party inland to find out what sort of people the inhabitants were, two of my men, together with a messenger. When they had left the ships they found a well-­‐worn track. At the end of the path they came across the Laestrygonians, people of monstrous size, who made their murderous intentions clear, pouncing on one of my men to eat him for supper. The other two sprang back and fled, and managed to make their way back to the ships. Meanwhile, they raised a huge cry through the town, which brought countless numbers of massive and powerful Laestrygonians running up from every side, more like giants then men. Standing at the top of the cliffs they ambushed my fleet with lumps of rock such as no ordinary man could lift; and the din that now rose from the ships, where the groans of dying men could be heard above the splintering of timbers, was appalling. They carried them off like fishes on a spear to make their loathsome meal. While this massacre was going on in the harbour, I drew my sword, and shouted to the crew to row their oars if they wished to save their lives. The fear of death on them, they struck the water together, and we shot out to sea, leaving those frowning cliffs behind. My ship was safe, and we travelled on with heavy hearts, grieving for the loss of our dear friends, but glad for our own escape from death. 5 3. Circe The Sorceress And so we came to the island of the beautiful Circe, a formidable goddess with a mortal woman’s voice. We brought our ship into the shelter of the harbour without making a sound, the only ship remaining of my fleet, after the cannibalism of the fearful Laestrygonian giants. And when we had disembarked, we lay on the beach for two days and nights, utterly exhausted, our hearts aching with grief. Nor could my men forget the unbridled savagery of the man-­‐eating Cyclops. When dawn approached, I took my spear and sword in hand, left the ship, and struck inland, making for a vantage point where I might see signs of cultivation or hear men’s voices. I climbed a rocky height, and on reaching the top I saw smoke rising from Circe’s house in a clearing among the trees. I divided my well-­‐armed crew into two parties, with a leader for each. Of one party I myself took charge; the other I gave to the noble Eurylochus. Then we shook lots and out jumped the lot of the great-­‐hearted Eurylochus, so off he went with his twenty-­‐two men. In a clearing in a glade they came upon Circe’s house, built of polished stone. Prowling about the place were the mountain wolves and lions that Circe has bewitched with her magic drugs. Terrified at the sight of these ferocious beasts, they could hear Circe within, singing her beautiful voice as she went to and fro on her everlasting loom. They called and Circe came out at once, opened the doors, and invited them to enter. In their innocence, the whole party followed her in. But Eurylochus suspected a trap and stayed outside. Circe showed the rest into her hall, gave them seats to sit on, and prepared them a mixture of cheese, honey and wine. But into this dish she mixed a magic drug, to make them lose all memory of their homeland. And when they had emptied the bowls which she had handed them, she drove them with blows of a stick into the pigsties. Now they had pigs’ heads, and they grunted like pigs, but their minds were human as before. So, weeping, they were penned in their sties. Then Circe flung them some nuts, acorns and berries, the usual food of pigs that wallow in the mud. Meanwhile Eurylochus came back to the ship to report the catastrophe his party had met with. He was in such an anguish that his eyes filled with tears, and told the story. When I heard the story I slung my sword and bow over my shoulder, and struck inland. But, threading my way through the enchanted glades, I was nearing the sorceress’ palace when I met Hermes, the messenger god, who said: ‘Where are you off to now, fellow, wandering alone through the wilds, with your friends in Circe’s house penned like pigs in their sties? Have you come to free them? I think you are more likely to stay with them yourself and never see your home. However, I will deliver you from your trouble. Look: here is a drug of real virtue that you must take with you into Circe’s palace; it will make you immune from evil. I will tell you how she works her black magic. She will begin by preparing you a mixture, into which she will put her drug. But she will be unable to enchant you, for this antidote will rob it of its power. I will tell you exactly what to do. When Circe strikes you with her wand, draw your sword and rush at her as if you mean to kill her. She will shrink from you in terror and offer you favours. You must not refuse her favours, but make her swear a solemn oath by the gods not to try any more of her tricks on you, or she may rob you of your manhood.’ Then Hermes handed me a herb he had plucked, a black-­‐root and milk-­‐white flower, a dangerous plant for mortals. But the gods, after all, can do anything. Hermes went off 6 through the island forest with his winged sandals, while I with a heart oppressed by many dark forebodings pursued my way to Circe’s home. Circe came out at once, opened the doors, and invited me to enter. Filled with misgivings, I entered and she gave me a seat to sit on, and prepared me a mixture of cheese, honey and wine. With evil in her heart she dropped in the drug. She gave me the bowl and I drained it, without suffering any magic effects. She struck me with her wand and shouted, ‘Off to the pigsty, and lie down with your friends.’ I snatched my sword from my hip and rushed at her as though I meant to kill her. With a shriek she clutched my knees: ‘Who are you and where do you come from?’ she asked, and her words had wings. ‘Where is your homeland? I am amazed to see my drug does not work its magic. Never have I known a man who could resist that drug. You must have a heart in you that is proof against all enchantment. I am sure you are Odysseus, the man of many tricks, the one who Hermes told me always to expect on his way back from Troy. But now put up your sword so that we may trust one another.’ ‘Circe,’ I answered her, ‘how can you ask me to be gentle with you, you who have turned my friends into pigs here in your house, and now you try and rob me of my manhood? Nothing, goddess, will persuade me unless you swear a solemn oath that you have no other mischief in store for me.’ Circe at once swore as I ordered her. And she saw that I was in deep anguish. ‘Odysseus, do you fear another trap? You need have no fears: I have given you a solemn oath to do you no harm.’ ‘Circe,’ I answered her, ‘could any honourable man bear to taste food or drink before he had feed his men and seen them face to face? If you are sincere, give them their liberty and let me set eyes on my loyal followers.’ Wand in hand, Circe went straight out of the hall, threw open the pigsty, and drove them out, looking exactly like swine. She smeared them all in some new ointment. Then the deadly potion wore off; they became men again and looked much younger, more handsome and taller than before. Circe told me to gather the rest of my loyal company, and I fetched them. And Circe said to them: ‘Eat and drink, til you are once more the men you were when you sailed from your homes in rugged Ithaka to Troy. You are worn out and dispirited, always brooding on the hardships of your travels. Your sufferings have been so continuous that you have lost all pleasure in living.’ We stayed on for day after day for a whole year, feasting on lavish meat and mellow wine. But as the months and seasons went by my companions asked me: ‘What possesses you to stay on here? It’s time you thought of Ithaka, your own country.’ This was enough: my proud heart was convinced. I went to Circe, and she listened to my winged words: ‘Circe, keep that promise which you once made to me, to send me home. I am eager now to be gone, and so are my men.’ ‘Do not stay unwillingly. But first you must make another journey and find your way to the Halls of Hades and dread Persephone, to consult the soul of Teiresias, the bling Theban prophet. His sight is impaired, and dead though he is, Persephone has granted him, and him alone, wisdom and foresight. The others are shadows.’ This news broke my heart. I had no further use for life, no wish to see the sun any more. I questioned her: ‘Circe, who is to guide me on my way? No one has ever sailed a ship into Hell.’ ‘Odysseus, the North Wind will blow your ship on her way, and you will come to Persephone’s grove and Hades’ Kingdom of Decay. There, at the River Styx, make Teiresias an offering of the finest sheep in your flock, and sacrifice a ram. Teiresias will prophesy your route, your journey and how you will reach home across the seas.’ I told my men, ‘No doubt you imagine that you are bound for home and for Ithaka. But Circe has marked out for us a very different route – to the Halls of Hades to seek the advice of the spirit Teiresias.’ When I told them this they were heart-­‐broken. We made our way back to our ships with heavy hearts. And Circe left us a sheep and a ram by our ship. 7 4. Hades and Teiresias So our ship reached the furthest parts of the deep-­‐flowing ocean as we sped across the sea all day, til the sun went down and all the ways grew dark, wrapped in mist and fog. Dreadful night spread its cloak over the world. We took hold of the sacrificial victims, and poured offerings to the dead, a mixture of honey, milk and wine. I took the sheep and the ram and cut their throats so the dark red blood poured out. And now the souls of the dead came swarming out from Hades with an eerie clamour. The spirit of Teiresias the blind prophet now approached, and addressed me: ‘Odysseus, man of many tricks, hero of nimble wits, man of misfortune, what has brought you to forsake the sunlight and visit the dead in this joyous place? Step back so I can drink the blood and prophesy the truth to you’. I drew back, sheathing my sword. And when the blind prophet of great foresight had drunk the dark blood, he uttered these words: ‘Odysseus, you seek a happy way home. But a god is going to make your journey hard. I cannot think you will escape Poseidon the Earthshaker, who still resents you, enraged that you blinded his beloved son. Even so, you and your friends may yet reach Ithaka, though not without suffering, if only you have the strength of will to control your men’s appetites and your own from the cattle on the island of the Sun God. If you leave them untouched and fix your mind on returning home, there is some chance that all of you may yet reach Ithaka. But if you hurt them, I predict that your ship and company will be destroyed, and if you yourself escape, you will reach home in a wretched state, having lost all your comrades, and you will find trouble in your house – insolent men eating up your livelihood, offering wedding gifts to your royal wife. This is a truth I have told you.’ The spirit of the blind Teiresias had spoken his prophecies and now withdrew into the Halls of Hades. I was approached next by the soul of Agamemnon, King of Kings, King of all the Greeks. He came in sorrow, and as soon as he had drunk the dark blood, he recognised me, and said: ‘Odysseus of the cunning tricks, my accursed wife Clytaemnestra put me to death. This was my pitiful end. Never be too trustful of your wife, nor show her all that is in your mind. Reveal a little of your plans to her, but keep the rest to yourself. Not that your wife, Odysseus, will ever murder you: she is far too loyal in her thoughts and feelings. The wise Penelope! She was a young woman when we made our way to war, with a baby son. And now, I suppose, Telemachus has begun to take his seat among men. And now I give you a piece of advice: take it to heart. Do not sail openly into port when you reach your homeland. Make a secret approach. But can you give me the truth about my son? Have you heard of him as still alive?’ ‘Agamemnon,’ I answered him, ‘why ask me that? I have no idea whether he is dead or alive. It does no good to utter empty words.’ And we stood there grieving and joyless. And now there came the soul of Achilles, who recognised me and drank blood. ‘Odysseus, master of tricks, what next, dauntless man? What greater exploit can surpass your voyage here? How did you dare come down to Hades realm, where the dead live on as the mindless disembodied ghosts?’ ‘Achilles,’ I answered him, ‘fiercest of all the Greeks, I came to consult with the blind prophet Teiresias in the hope of finding out from him how I could reach rocky Ithaka. For I have not managed to reach my island, but have been dogged by misfortune. But you, Achilles, are fortunate! You have great power amongst the dead. Do not grieve at your death, Achilles.’ ‘And do not make light of death, cunning Odysseus,’ he replied. ‘I would rather work the soil on earth than be King of all these lifeless dead.’ 8 The mourning ghosts of all the other dead and departed pressed round me now, each with some question for me. The only soul that stood back was Ajax. He was still embittered by the defeat that I had inflicted on him at the ships for the arms of Achilles. I wish I had never won such a prize – the arms that brought Ajax to his grave. I called to him now, and tried to placate him: ‘Ajax, could not even death itself make you forget your anger with me on account of those fateful arms? It was the gods who made them a curse to us Greeks! What a tower of strength we lost when you fell! We have never ceased to mourn your death as truly as we lament Achilles. Curb your anger and conquer your stubborn pride.’ Ajax made no reply, but went off in the Halls of Hades to join the souls of the other dead. And I saw King Minos of Crete, who had spawned the Minotaur, enslaved the Athenians and imprisoned the beast in the labyrinth. I saw the broken Icarus, who had refused to listen to the wise warning of his father Daedalus. And I saw the broken Aegeus, who had thrown himself off the cliffs after seeing the ship of his son Theseus return from Crete to Athens with a black sail, thinking him killed. I also saw the awful agonies that Tantalus has to bear. Tantalus was in a pool of water that nearly reached his chin, and his thirst drove him to unceasing efforts; but could never reach the water to drink it; whenever he stooped in his eagerness to drink, it disappeared. Trees spread their foliage over the pool and dangled fruits above his head – apples and delicious pears; but whenever Tantalus made to grasp them, the wind would toss them up towards the shadowy clouds, in tantalising torture. Then I saw the torture of Sisyphus, as he wrestled a huge rock with both hands. Bracing himself and thrusting with hands and feet he pushed the boulder uphill to the top. But every time, as he was about to send it toppling over the crest, its sheer weight turned it back, and once more again towards the plain the pitiless rock rolled down. So he once more had to wrestle with the thing and push it up, while the sweat poured from his limbs and the dust rose high above his head. Next after him I observed the mighty Hercules. Terrible was the Nemean lion’s skin he wore, the lion he had killed with his great club, and the tusks of the Erymanthian boar. Miraculous were the scars, depicting scenes of bulls, boars, lions, the Hydra, man-­‐eating birds and horses, the Amazon warriors and Cerberus the three-­‐headed hell-­‐hound of Hades himself. One look was enough to tell who Hercules was, and after drinking the dark blood, he addressed me with winged words: ‘Odysseus, man of many tricks, unhappy man! So you too are working out some such miserable doom as I endured when I lived in the light of the sun. Though I was a son of Zeus, unending troubles came my way. For I was bound in service to a master far beneath my rank, King Eurystheus, who used to set me the most arduous labours. Once, thinking no other task more difficult, he sent me down here to bring back the hellhound of Hades, Cerberus. And I succeeded in capturing him and leading him out of Hades’ realm. Hercules said no more, and withdrew into the halls of Hades, while I lingered on, hoping to see other heroes who had perished long ago, men like Midas, Theseus and Perseus, those legendary children of the gods, the mutilated Patroclus, who fell to the Trojan warrior prince Hector, and the mutilated Hector, who fell to lion-­‐hearted Achilles, and heroines like Hippolyta, killed by Achilles, Ariadne, who helped Theseus but was betrayed by him, and Medea, who helped Jason but was betrayed by him. But before that could happen, all the tribes of the dead came up and gathered round me in their tens of thousands, making their eerie clamour. Sheer panic turned me pale. I feared the dread Persephone might send up from Hades halls the gorgon head of Medusa. I hurried to my ship and told my men to embark. And so we left the land of the dead, in all its horror. 9 5. Scylla and Charybdis And so it was that we left the dread halls of Hades, and by dawn we had returned to the island of Circe. Circe came hurrying up with a plentiful supply of meat and red wine: ‘What bravery,’ said the glorious sorceress, ‘to descend alive into the House of Hades! Other men die once; you will now die twice. But come, spend the rest of your day here, enjoying this food and wine, and at daybreak tomorrow you shall set sail. I myself will give you your route and make everything clear, to save you from disasters you may suffer as a result of evil scheming on land or sea, by man or God in the Halls of great Olympus.’ We were not difficult to persuade. So the whole day long till sunset we sat and feasted on our rich supply of dark meat and mellow wine. When sun sank and darkness fell, my men settled down for the night by the ship; but Circe took me by the hand, led me away from my comrades, and me sit down and tell her everything, how I saw the blind prophet Teiresias, the great Achilles and Ajax, King Minos and Icarus, who had not listened to his father Daedalus, and the broken Aegeus, father of Theseus; how I saw the tortured Tantalus, who could not quench his thirst or hunger; and Sisyphus, who always had to heave his rock uphill for all eternity; how I met Hercules, who had wrestled with Cerberus in the halls of Hades; and how I longed to see Theseus, Perseus and Midas, Patroclus and Hector, as well as Hippolyta, Ariadne and Medea -­‐ but that did not come to pass. When I had given her the whole tale, Circe said: ‘Very well; all that is done with now. But listen to my words – and some god will recall them to your mind. Your next encounter will be with the Sirens, who bewitch everybody who approaches them and wrecks their ships. There is no homecoming for the man who draws near them unawares and hears the Sirens voices, for with their high clear song the Sirens bewitch him, as they sit with their cliffs piled high with the skeletons of men, whose withered skin hangs still on their bones. Drive your ship past the spot, to prevent any of your crew from hearing, soften some beeswax and plug their ears with it. But if you wish to listen yourself, lash yourself to the mast. But if you command and beg your men to release you, they must add to the bonds that already hold you fast. ‘When your crew have carried you past the Sirens, there lie two rocks, which rear their sharp peaks up to the very sky, and are capped by black clouds, and half-­‐way up there is a murky cavern. It is the home of Scylla, a dreadful and repulsive creature. She has six necks, each ending in a grisly head with triple rows of fangs, set thick and close, and darkly menacing death. Her heads protrude from the fearful abyss. No crew can ever boast that they have ever sailed their ship past Scylla unscathed, for from every vessel she snatches and carries off a six men, one with each of her heads. ‘Below the other of the rocks lies dread Charybdis, a whirlpool which sucks the dark waters down, spews them up and swallows ships down in its wild and whirling dread. Heaven keep you from Charybdis, for once the whirlpool has you, not even Poseidon the Earthshaker could save you from destruction then. No, you must hug Scylla’s rock and with all speed drive your ship through, since it is far better to lose six men than your whole crew.’ ‘Yes, goddess,’ I replied, ‘but tell me this. I must be quite clear about it. Could I not somehow steer clear of deadly Charybdis, yet ward off Scylla when she attacks my crew?’ ‘Stubborn fool’ the beautiful goddess Circe replied. ‘Again you are spoiling for a fight and looking for trouble! Are you not prepared to give in to the immortal gods? I tell you, Scylla was not born for death: she is an undying fiend. She is a thing of terror, invincible, ferocious and impossible to fight. No, against her there is no defence, and the best course of action is flight. For if you waste time by the rock in putting on your armour, I am afraid she may dart out once more, make a grab with all six heads and snatch another six of your crew. SO drive your ship past with all your might. Next you will reach the island of the Sun God’s Cattle. As the blind prophet Teiresias prophesised, if you leave them untouched and fix your mind on getting home, there is some 10 chance that all of you may reach Ithaka, though not without suffering. But if you hurt the cattle, Teiresias has predicted the destruction of your ship and your company. And if you yourself escape, you will reach home in a wretched state, having lost all your comrades, and you will find trouble in your house – insolent men eating up your livelihood, offering wedding gifts to your royal wife.’ As Circe came to an end, the glorious goddess left me and made her way inland, to send us the friendly escort of a favourable wind, to fill the sails of our ship. We set the course between Scylla and Charybdis. Then, disturbed in my spirit, I addressed my men. ‘My friends,’ I said, ‘it is not right that only one or two of us should know the prophecies that blind Teiresias and divine Circe have made to me, and I am going to pass them on to you, so that we all may be forewarned, whether we die, or escape the worst and save our lives. Her first warning concerned the Sirens with their divine song. We must beware of them and steer clear of them, and put wax in our ears to avoid their alluring song, but I alone must hear their voices. You must bind me very tight, lashed to the mast of our ship so that I cannot stir from the spot. And even if I command and beg you to release me, you must tighten and add to my bonds.’ In this way I explained every detail to my men. In the meantime our good ship, with that friendly breeze to drive her, approached the Sirens’ isle. But now the wind dropped, some power lulled the waves, and breathless calm set in. My men drew in the sail and churned the white water with their oars. Meanwhile I took a lump of wax and cut it up small with my sharp sword. I gave all my men in turn some wax to plug their ears with, so they could not hear the Sirens’ tempting call to death. Then they bound me hand and foot, lashing me to the mast itself. This done, they once more churned the white water with their oars. We made good progress and has just come within call of the shore when the Sirens became aware that there was a ship bearing down on them, and broke into their high, clear song: ‘Draw near, Odysseus, man of many tales, and bring your ship to rest so that you may hear our voices. No sea captain ever sailed his ship past this point without listening to the honey-­‐ sweet tones that flow from our lips, and no one who has listened has not been delighted. We know all that the Greeks and Trojans suffered on the field of Troy, and we know of the Greeks Agamemnon, Menelaos, Achilles, Patroclus and Ajax, and the Trojans Priam, Hector and Paris, and the women Helen and Briseis, who caused so much conflict. Draw near, Odysseus, man of many tales.’ This was the sweet song the Sirens sang, and my heart was filled with such a longing to listen that I ordered my men to set me free, gesturing with my eyes. But no matter how I raged and curses, commanded and begged them, desperate to draw nearer to the honey-­‐sweet tones, my men swung forward with their oars and rowed ahead, while Eurylochus tightened my ropes and added more. When they had rowed past the Sirens and could no longer hear, my good companions were quick to clear their ears of wax, and free me. We had no sooner put this island behind us than I saw the black clouds gather and a raging surf, and heard the thunder of the breakers. We sailed on, but I could not catch a glimpse of Scylla anywhere, though I searched the cliffs in every part til my eyes were tired. Thus we sailed up the straights in terror, for on one side we had Scylla, and on the other the awful Charybdis, sucking down the salt water in her dreadful way, stirring to the depths and seething like a cauldron, the whole interior vortex exposed, the rocks re-­‐echoing to her fearful roar. My men turned pale with terror; and now, while all eyes were on the impending catastrophe of Charybdis, Scylla descended in the gloom and snatched out of my ship six of the strongest men. I saw their arms and legs dangling high in the air above my head. ‘Odysseus’ they called out to me in their anguish. But Scylla had whisked my comrades, struggling, up to the rocks. There she devoured them at her door, shrieking and stretching out their hands to me in their last desperate throes. In all I have gone through on the seas, I have never had to witness a more pitiable sight than that. 11 6. The Sun God’s Cattle When we had left the Sirens, Scylla, and dread Charybdis behind, we soon reached the island of the Sun, where the Sun God Apollo kept his splendid cattle. From where I was on board, out to sea, I could hear the cows as they were stalled for the night. And there came to me the words of Teiresias, the blind prophet from Thebes, and of Circe the divine goddess and sorceress, who had each been so insistent in warning me to avoid this Island of the Sun, the comforter of mankind. So with an aching heart I addressed my men: ‘Comrades in suffering,’ I said, ‘listen to me while I tell you what Teiresias and Circe predicted. They warned me insistently to keep clear of the island of the Sun God Apollo, for there, they said, our deadliest peril lurks. So let us drive the ship past this island.’ My men were heartbroken when they head this, and Eurylochus spoke up at once in a hostile manner. ‘Odysseus, you are one of those hard men whose spirit never flags and whose body never tires. You must be made of iron through and through to forbid your men, worn out by efforts and lack of sleep, to set foot on dry land, with the chance of cooking ourselves a tasty supper in this sun-­‐kissed island. Instead, you expect us, just as we are, with night coming on fast, to abandon this island and go wandering over the foggy sea. It is at night that high winds wreck ships. What port could we reach to save ourselves from sinking f a sudden storm starts up? There’s nothing like the South wind or wicked West for smashing a ship to pieces. And the gods don't ask! No, let us give in to the evening dusk, and cook our supper by the side of the ship. In the morning we can go on board and put out into open sea.’ This speech of Eurylochus was greeted by applause from all the rest, and it was brought home to me that some god really had a calamity in store for us. I answered him with winged words: ‘Eurylochus, I am one against many, and you force my hand. Very well. But I call on every man of you to give his solemn promise that if we come across a herd of cattle, he will not kill a single ox in a wanton fit of recklessness. Just sit peacefully and eat the food that the goddess Circe has provided.’ The crew agreed and gave the promise I had asked for. Accordingly, when all had sworn and completed the oath, we brought the good ship to anchor in a sheltered cove, with fresh water at hand, and the men disembarked and proceeded to prepare their supper. When they had satisfied their hunger and thirst, their thoughts returned to their comrades, who had been eaten alive by Polyphemous the Cyclops, skewered by the Laestrygonian giants and devoured by Scylla. And their thoughts also returned to the encounters with Aeolus of the floating island Aeolia and the bag of winds, the tempting Siren song, and the sorceress Circe’s magic drug, wicked transformations and soothing ointment. When the stars had reached their zenith in the night, Zeus, still cursing me for pretending to be mad to avoid fighting at Troy, whipped up a gale of incredible violence. He covered the land and sea with dark clouds, and blazed his thunderbolts round the island in a great tempest. When dawn approached, I ordered all my men to gather round, and gave them a warning. ‘My friends,’ I said, ‘since we have plenty of food and drink on board, let us keep our hands off these cattle, or we shall come to grief. For the cows and the fine sheep you have seen belong to that formidable god, the Sun, whose eyes and ears miss nothing.’ My strong-­‐willed company accepted this. And now for a whole month the South Wind blew without a pause, and after came both the South and West Winds, unrelenting. The men, so 12 long as they had their bread and red wine lasted, kept their hands off the cattle as they valued their lives. But when the provisions in the ship gave out and the pangs of hunger sent them wandering with barbed hooks in any quest of any game, fishes or birds, which might come to hand, I went inland to pray to the gods in the hope that one of them might show me the way to escape. But the gods of Mount Olympus cast me into a great sleep. In the meantime Eurylochus was plotting a wicked scheme with his mates. ‘My comrades in suffering’ he said, ‘listen to what I have to say. To us wretched men, all forms of death are abominable, but death by starvation is the most miserable way to meet one’s doom. So come, let us round up the best of the Sun God Apollo’s cows, and sacrifice them in honour of the immortals who live in great Olympus. If we ever reach our homeland in Ithaka, our first act will be to build the Sun God Apollo a temple and fill it with precious offerings. But if in anger at the loss of his cattle, he chooses to wreck our ship, I would sooner drown instantly than starve slowly.’ His ideas found favour with the rest, and they proceeded at once to round up the Sun God Apollo’s cattle. The men gathered round the cattle, made their prayers to the gods, and their prayers done, they slit the cow’s throats, then cut out slices from the thighs, and spitted them on skewers. Then it was that I suddenly awoke from my deep sleep, and started my way back to the coast and the ship. Directly I came near my ship, the sweet smell of roasting meat was wafting all about me. I exclaimed in horror, ‘Zeus and all you other gods who live forever! So it was to ruin me that you lulled me into that cruel sleep, while left to themselves the men planned this awful crime!’ In a fury the Sun God Apollo cried out to the immortal Gods of Olympus: ‘Zeus and all you other gods who live forever, take vengeance on the followers of Odysseus! They have criminally killed my cattle, the cattle that gave me such joy every day as I climbed the starry sky and sank once more to earth. Avenge my slaughtered cows!’ And Zeus in Olympus replied, ‘Sun-­‐God Apollo, shine on for the immortals and for the mortal men on the fruitful earth. As for the culprits, I will soon strike their ship with a blinding thunderbolt out on the wine-­‐dark sea and smash it to pieces.’ So Calypso later told me, who herself had heard it from Hermes, the messenger God. When I had come down to the sea and reached the ship, I rebuked and comforted my men. But we could find no way of mending matters: the cows were dead. And the gods soon began to show my crew ominous portents. The carcasses of the cattle began to crawl and roam about; the meat, red and raw, bellowed on the spits, and a sound of lowing cattle could be heard. Then Zeus cleared the fury of the storm, so we quickly embarked and set out into the open sea. When we had left the island and nothing but sky and water could be seen, Zeus brought a dark cloud to rest above the hollow ship so the sea was darkened by its shadow. A howling wind suddenly sprang up from the West and hit us with hurricane force. The mast toppled and struck the helmsman and smashed in all the bones of his skull. Zeus thundered and struck the vessel with lightning. The ship reeled from the blow and filled with the smell of sulphur. Flung overboard, my men descended to the depths and drowned: the King of the Gods and the Sea God Poseidon saw to that. A great wave tore me overboard, and I became the sport of the furious winds, adrift on timber, carried back toward dread Charybdis the whirlpool and Scylla’s rock. Charybdis was sucking the salt water down, and I swung up to a great tree branch, on which I got a tight grip and clung like a bat. I could find no foothold to support me, nor had I any way to climb the tree. I clung grimly on, hoping Scylla wound not spy me, otherwise nothing would save me from certain death. At long last the mast appeared, and I clambered on. Nine days of drifting followed. On the tenth, the gods washed me up on the island of Calypso. 13 7. Calypso’s Captivity Fog smothered the face of the ocean. Neither the vengeful Sun God Apollo above nor the vengeful Sea God Poseidon below sighted Odysseus as he drifted onto the shores of Ogyia, after narrowly escaping Scylla and Charybdis once more. He awoke to find himself in the cave of a sea nymph. The cave had everything a sea nymph’s heart could desire: bee hives full of honey, vines full of grapes, orchid groves full of olives and pomegranate trees full of fruit, lined soft with sheep’s fleeces. Her cave was a sunny cleft high in a flowery hillside. And then he saw a beautiful sea nymph. ‘Odysseus, man of many tricks, man of the wandering ways, man of many misfortunes, how many times has Hermes told me you would come to my island of Ogyia? How could I let you die after waiting all these years? I am Calypso, Calypso the sea nymph, and you are the husband I have waited for all my life. I knew you would arrive, and now you’ll stay with me forever.’ ‘Calypso, I am truly grateful. But I am already married! My wife and son are waiting in my island kingdom of Ithaka. I must set sail,’ Odysseus replied. ‘Odysseus, you have no ship,’ replied Calypso. ‘Then you must help me build one!’ Odysseus replied. ‘I have no ship, and I am the only person living on this island. The forests and woods here are my subjects. They would never allow themselves to be built into a ship,’ Calypso replied. ‘My wife Penelope… -­‐ ’ Odysseus started, but Calypso interrupted him: ‘-­‐ … is old and wrinkled now. I will never grow old: I am immortal.’ And Odysseus knew how the little bird feels when it lands on lime twigs to rest and finds its feet elf stuck fast. And he threw himself down on the fleeces in despair. And Calypso smiled and said ‘Soon you will love me. Wait and see…’ Every morning Odysseus went down to the shore, lit a fire on the beach, made a sacrifice to the immortal Gods and prayed for their help. But though Hermes was the god of travellers, and though Athena, the goddess of wisdom admired him, the power of Zeus of thunder, Poseidon of the sea and Apollo of the sun was mighty, and they had forbidden all the gods to help him. Year after year, every morning Odysseus lit a fire, made a sacrifice, and prayed to the gods, but no to avail: for seven long years he was fated to stay with Calypso, though longing to see his homeland Ithaka, his wife Penelope and his son Telemachus. The imprisonment of Odysseus in Calypso’s home weighed heavy on Athena’s heart, and she now recalled the tales of his misfortunes to the minds of the gods: ‘Father Zeus, and you other gods who live forever, think of Odysseus! Not one of the people he once ruled as King in Ithaka gives him a single thought. He is left to languish in misery in the island home of the sea nymph Calypso, who keeps him captive there. And meanwhile wicked suitors are causing trouble in his home, eating up his livelihood, offering wedding gifts to his royal wife.’ ‘Nonsense, my child!’ replied the Cloud Gatherer. ‘How could I ever forget Odysseus the trickster, who pretended to be mad to avoid going to Troy? How could I forget his trick of the Wooden Horse of Troy, that after ten long years settled forever the war between the Greeks and the Trojans, the war that not even great Achilles or Hector, Agamemnon or Ajax could settle? And how could I forget his travels since, his trick to escape the Cyclops, his confrontations with the man-­‐eating Laestrygonian giants, his escape from Circe, the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, his journey to the Underworld and the halls of Hades? How could I forget such a cunning and courageous hero of the Greeks? His cunning and courage have earned his homecoming. It is Poseidon the Earth Shaker who is so vengeful on account of his son Poseidon, and Apollo the Sun Bringer who is so vengeful on account of his cattle. But 14 they will relent. For they will not be able to struggle on against the united will of the immortal gods.’ Bright-­‐eyed Athena, goddess of wisdom, answered him, ‘Father of ours, Son of Kronos, King of Gods, if it is now the pleasure of the gods that wise Odysseus shall return to Ithaka and loyal Penelope, let us send Hermes, the messenger god and god of travellers, to the island of Ogygia, so that he can tell Calypso the sea nymph of our decision.’ Zeus now turned to Hermes, the giant killer: ‘Hermes, as you are our messenger god, convey our decision. The long-­‐enduring Odysseus must now set sail for home. On the journey he shall have neither gods nor men to help him. Until he his home, the gods are free to harm him. He shall set sail on a raft put together by his own hands, and on the twentieth day, after great hardship, reach the island of the Phaeacians, who are close to the gods. They will convey him by ship to his own land. So he will reach his home, where he will find trouble, because his men ignored the prophecy of the blind prophet Teiresias in the Underworld, and killed the Sun God Apollo’s cattle. But once at home, the gods are free to help him.’ Hermes the god of travellers made his flight on his winged sandals, with the speed of the wind over the water and the boundless earth, swooping and skimming the waves of the oceans, until he came to the great cave of the Sea Nymph Calypso. He found her at home. The goddess Calypso knew him the moment she raised her eyes, for none of the immortal gods is a stranger. As fro lion hearted Odysseus, Hermes did not find him in the cave, for he was on the shore, tormenting himself with his heartache for home, his wife Penelope and his son Telemachus. The divine Calypso seated Hermes the giant killer on a golden chair, and asked him: ‘Hermes, god of thieves, what brings you here? You are an honoured and a welcome guest. Tell me what is in your mind, and I will gladly do what you ask of me, if I can and if it must be so.’ ‘As one immortal to another, as you ask me what has brought me here, I shall tell you frankly. It was Zeus who sent me. He says here you have a man who has been dogged by misfortune, who shared nine years of fighting round the walls of Troy, and left for home when they had sacked it on the tenth, and who has wandered the oceans in his great journey, his great odyssey, for nine long years now. Now Zeus bids you send him off without delay. He is not doomed to end his days on this island. He is destined to see his homeland once more. Calypso shuddered: ‘You are hard-­‐hearted, you gods, and unmatched for jealousy. Now it is my turn to incur the jealousy, envy and wrath of the gods for living with a mortal man – a man whom I rescued from death after Zeus had struck his ship with a lightning bolt as it sailed on the wine-­‐dark sea. If Zeus commands, I consent. But I will not help him on his way!’ ‘Then send him off at once,’ the giant killer said, ‘and so avoid provoking Zeus and the wrath of the gods, or we may punish you someday’. Calypso went to find Odysseus, and found him sitting on the shore in misery, torturing himself with heartache. The immortal nymph came and sat beside him now. ‘My unhappy one, don't go on grieving, don't waste any more of your life on this island. For I am ready with all my heart for you to leave. I wish you happiness. Yet if you had any inkling of the full measure of misery you are bound to endure before you reach your homeland, you would accept my immortality.’ And so it was with a heavy and a happy heart that Odysseus crafted a raft and a sail to catch the wind, and left the island of the sea nymph Calypso. 15 8. Poseidon’s Revenge So Odysseus set sail from the island of Calpyso, the immortal sea nymph who had imprisoned him for seven long years. He spread his sail to catch the wind and skilfully kept the raft on course. There he sat and never closed his eyes in sleep, but kept his eyes on the constellation of the stars by which he navigated. So for seventeen days he sailed. But now Poseidon, lord of the earthquake, spied him. The sight of Odysseus sailing over the seas enraged him. He marshalled the clouds and seizing his trident, stirred up the sea. He roused stormy blasts of every wind that blows, and covered the water with a canopy of cloud. The gale-­‐force East Wind, the tornado South Wind, tempestuous North and wicked West clashed together, rolling great waves in the tempest. Odysseus’ great, exhausted spirit trembled in anguish: ‘Poor wretch that I am, what will become of me after all? I fear the sea-­‐nymph Calypso prophesied well when she told me I am bound to endure my full measure of misery before I reach my homeland. The whole sky is heavy with clouds, the sea is seething, squalls from every quarter hurtle together. There is nothing for me now but sudden death. Those comrades of mine, Achilles and Patroclus, Agamemnon and Ajax, were blessed to fall long ago on the broad plains of Troy in immortal glory! If only I too could have met my fate and died the day Achilles died! I at least would have my glory; but now it seems I was predestined to a inglorious death.’ As he spoke, a mountainous wave, advancing with awesome speed, crashed down on him from above and whirled his raft around. He was torn from his raft, and the warring winds joined in one tremendous blow, which snapped the mast in two and flung the sail into the sea. Plunged underwater, he could not quickly fight his way up against the downrush of that almighty wave. But at last he reached the air and spat out the bitter seawater that had poured down his throat. Exhausted though he was, he did not forget his raft, but struck out after it through the waves, scrambled up, and tried to avoid the finality of death. The heavy seas thrust him with the current this way and that. On the brink of giving up, Odysseus took courage: ‘As long as the joints of the planks hold fast, I shall stay where I am and endure the suffering. But when the seas break up my raft, I’ll swim for it. I cannot now think of anything better.’ As Odysseus was turning over the last of his cunning intelligence in his heart and mind, Poseidon the earthshaker sent him another monstrous wave. Grim and menacing it curled above his head, then hurtled down and scattered his raft. Poseidon cursed him and prophesied: ‘So much for you! You blinded my son Polyphemous the Cyclops, and boasted so that everyone would know your name! Now you make your miserable way across the sea, and even if you make your homeland, you will find trouble in your home.’ With this, Poseidon lashed his chariot of sea-­‐horses and drove to his underwater palace. For two nights and two days Odysseus, the man of many misfortunes, was driven by the heavy seas. Time and again he thought he was doomed. But Athena, goddess of wisdom, decided to intervene. She checked all the winds, bidding them to calm down and go to sleep. And so on the third day, a breathless calm set in, and Odysseus, keeping an exhausted but sharp-­‐eyed look out, caught a glimpse of land close by as he was lifted by a mighty wave. With an angry roar the great seas were battering the rocky land, nothing but sharp reefs and jagged rocks. But wise and bright-­‐eyed Athena put it into his head to grab hold of a rock with both hands as he swept in. He clung there, groaning while the great waves swept by. But no sooner had he escaped its fury than its backward rush caught him with full force and flung him far out to sea. Pieces of skin stripped from his sturdy hands were left sticking to the crag. Athena held back the waves and currents and made the water smooth a path to the 16 coast. On land for the first time in days, Odysseus’ knees gave way and his sturdy arms sagged; he was exhausted by his struggle with the sea. All his flesh was swollen and streams of salt water gushed from his mouth and nostrils. He groaned: ‘Oh, what will happen to me now? What will become of me? I’m at my last gasp. I’m an easy meal for beasts of prey.’ And Athena filled his eyes with sleep and sealed his lids – sleep to soothe his pain and utter exhaustion. So there he slept, the much-­‐enduring Odysseus, and Athena came to the country of the Phaeacians. And she arranged for Odysseus to wake up and see the palace of the Phaeacian city. Athena led him to the palace quickly, and Odysseus followed in the footsteps of the goddess of wisdom. Bronze walls gleamed with the radiance of the sun or moon. Golden doors hung on posts of silver which were set in the bronze threshold. On either side of the door were gold and silver dogs, which Haepheastus, god of the hearth and forge had made with skill to watch over the Phaeacian palace. Such were the glorious gifts the gods bestowed on Alcinous King of the Phaeacians. The bright-­‐eyed goddess took him to King Alcinous. And King Alcinous took Odysseus by the hand, and said: ‘Captains and Counsellors of the Phaeacians , mix a bowl of wine and fill the cups of all the company in the hall, so we may make a drink-­‐offering to Zeus the Thunderer, patron of suppliants, who deserve respect.’ ‘Alcinous,’ Odysseus replied, ‘Think of the wretches who in your experience have borne the heaviest load of sorrow, and I will match my griefs with theirs. Indeed I could tell you a tale of even greater woe, if I gave you an account of what by the gods’ will I have suffered. My heart is sick with grief; I have had hard times indeed. Let me see my homeland, and I am content to breathe my last.’ So Alcinous asked him: ‘Who are you? Where do you come from? And where have you been driven in your wandering across the seas?’ ‘King Alcinous,’ the resourceful Odysseus began his tale, ‘I will tell you the tale of my great endurance. I am Odysseus, man of many tricks and many misfortunes. Since defeating the Trojans at Troy with the Wooden Horse, I have lost all my comrades: they have been devoured by the Cyclops; cursed by the Sea God Poseidon; skewered by the Laestrygonian giants; opened Aelius’ bag of many winds; transformed into pigs by Circe; travelled over the River Styx to the Underworld; confronted by Achilles and Agamemnon, Ajax and the blind prophet Teiresias; witnessed the torture of Tantalus and Sisyphus; escaped the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis; cursed by the Sun God; shipwrecked on the island of Calypso; I have wandered for nine long years, all the time longing to see my homeland Ithaka, my wife Penelope and my son Telemachus.’ Held in the spell of his words, they all remained still and silent through the shadowy hall, til Alcinous rose to address his counsellors: ‘Captains and Counsellors of the Phaeacians, this stranger is indeed Odysseus the resourceful, Odysseus the courageous. He asks for passage home. Listen while I tell you what is in my mind. Let us make arrangements to escort him. We will safeguard this stranger on the way from any further hardship and give him safe passage to his homeland. After which he must suffer whatever destiny and the relentless fate spun for him with the first thread of life when he came from his mother’s womb. These are my orders.’ The ship left, and Odysseus slept and did not wake up until after the ship reached Ithaka, leaving him on the beach. Poseidon the Sea God was passing in his sea-­‐horse chariot. He raised his hand to punish those who helped Odysseus, the man who killed his son, Polyphemous the Cyclops. In a flash, the ship turned to stone. Poseidon smiled and rode on. 17 9. Telemachus and Penelope Odysseus awoke from sleep on his native soil. After so long as absence, he now failed to recognise it, because Athena, goddess of wisdom, had thrown a mist over the palace. Her intention was to make him unrecognisable, to tell him how things stood, to prevent him from being recognised by his wife, friends or people before the trouble in his home was dealt with. So Athena appeared to Odysseus, and addressed him with winged words: ‘Odysseus, you have reached your island homeland of Ithaka. I am Athena, goddess of wisdom, who stands by your side and guards you in your wanderings. It was I who made the Phaeacians take you here so kindly. But the prophecy has come true, because your men ignored the prophecy of the blind prophet Teiresias in the Underworld, and killed the Sun God Apollo’s cattle. Wicked suitors are causing trouble in your home, eating up your livelihood, offering wedding gifts to your royal wife Penelope. All this time she has waited for your homecoming, with loyalty wishing for your return. I am here to make a cunning scheme with you, to warn you of all the trials you will have to go through within your palace. Tell not a single person, man or woman, that you are back from your wanderings; but endure all aggravation in silence.’ ‘By Olympus! I would certainly have come to the same end as Agamemnon directly as I set foot in my house, had you not made this clear to me. But come, devise some ingenious scheme to punish these miscreants. And take your stand at my side, as you did on the day when we tricked the Trojans with the Wooden Horse as a victory gift, and burnt the topless towers of great Troy.’ ‘I will indeed stand by your side. I shall not forget you when the time comes for this trial of ours. But now the scheme! I am going to change you beyond all recognition; I shall clothe you in rags, wither your skin and dim your bright eyes until you are repulsive and loathsome, even to your wife Penelope and son Telemachus who you left at home. Now for your part – you must go to the swineherd in charge of your pigs. His heart is loyal and devoted to your son Telemachus and wise Penelope.’ And Athena withered his skin, robbed his head of hair, covered his body in wrinkles, dimmed his bright eyes, and transformed his clothing into a shabby cloak, grimy rags and a filthy tunic. Then she left his company. Odysseus hurried down the rough, dusty path to the swineherd’s hut. Eumaeus the swineherd has been ordered to send several hogs to the arrogant Suitors to slaughter and feed on the flesh. Eumaeus thought Odysseus was a beggar, and addressed him: ‘Come in, my friend, you must be hungry. Have you any news? Did you hear what happened to King Odysseus? He never came back from Troy. The gods give me pain and grief! Here I sit, yearning for the best of masters, fattening his hogs for others to eat, while he, likely starving, is lost in foreign lands and strange places – if indeed he is still alive. But follow me, old man, let us go to my hut, when you can have all the bread and wine you want.’ Suddenly, the door opened. In came a young man. ‘Prince Telemachus!’ the swineherd gasped. ‘Come in, come in, and avoid that terrible gang of evil Suitors!’ And Athena transformed Odysseus back to youthful vigour, with a fresh cloak and tunic. Telemachus gave him a look of amazement, for fear that he might be a god. But patient, long-­‐enduring Odysseus said, ‘I am no god, Telemachus. Why do you take me for an immortal? But I am your father, for who you have endured so much sorrow and suffered so much pain.’ But Telemachus could not accept that it was his father, and asked if it this transformation was some trick. So Odysseus told him the disguise was the work of the goddess Athena. And so Telemachus embraced Odysseus, his long-­‐lost father. ‘Telemachus, my son, I came here on Athena’s prompting so that we could plan the destruction of our enemies. Tell me about the men who plot to steal my kingdom.’ ‘Father,’ said Telemachus, ‘you speak of the impossible. Two men could not possibly take on so many men. There are not just ten Suitors, or twenty, but hundreds. We may pay a cruel and 18 terrible price for the outrages you have come to avenge.’ ‘Listen carefully. Athena is on our side. I will come to the palace disguised as a wretched beggar. When I meet with insults, steel your heart. When Athena prompts me, I will give you a nod. Directly gather the weapons of war and stow them away. But if you are really my son and blood flows in your veins, see that not a soul hears Odysseus is back.’ Next morning, Odysseus went as a beggar with the swineherd when he drove his pigs to the palace. ‘Every day the princes come to ask Queen Penelope which one she will marry,’ said the swineherd. ‘She asks them to leave but they wont go away until she chooses one of them. They have done this for years, eating up your livelihood,’ he sighed. Odysseus hurried into the great hall where the suitors were eating and drinking. He picked up a bowl and went to the table, to beg for food and find out what the suitors plan to do. They cast him away in scorn. One threw a stool at Odysseus. Telemachus was furious, but he had promised his father to wait patiently, endure and say nothing. When Queen Penelope heard that a wandering beggar was in the palace, she sent her old nurse to fetch him. ‘This beggar may have met Odysseus on his wanderings,’ she said. ‘Maybe he will have news of my husband.’ Odysseus stood in the shadows. He was afraid his wife might recognise him although he was in disguise. He was heartbroken to see Penelope so sad. ‘Odysseus is alive and is very near to home now,’ he said to comfort her. ‘Thank you,’ said Penelope, ‘my nurse will look after you.’ An old lady brought in a bowl of water. She had known Odysseus since he was a child. She recognised an old scar on his leg. ‘Odysseus’ she gasped. ‘yes,’ he said, ‘but tell no one or my plan will be ruined.’ The nurse said, ‘your secret is safe with me.’ That evening, feasting on another of the swineherd Eumaeus’ hogs, the suitors shouted drunkenly: ‘Enough is enough! Penelope must choose one of us as her husband today. Then we will kill her son.’ Just then, Penelope came in, carrying a huge ivory bow. ‘This bow belonged to my husband, King Odysseus,’ she said. ‘I shall marry the man who is strong enough to put a string on it. But first he must also shoot an arrow through these twelve axes.’ She ordered the target to be set up. The suitors wanted to show how strong they were. Each one tried as hard as he could but could not string the bow. ‘It’s old and stiff,’ they shouted, and rubbed the bow will oil. They tried again and again but still could not bend it. At last, tired and cross, they gave up. ‘We’ll try again later,’ they said, ‘now bring us some food and wine.’ Odysseus stepped forward. ‘May I try?’ he asked. The suitors laughed. ‘A beggar wants to be King,’ they said. Odysseus picked up the bow, and, bending it easily, put on the string. He took an arrow, pulled the string and fired. The arrow shot through the axes and right into the centre of the target. The princes watched in horror. Athena, goddess of wisdom, had changed into a sparrow and was watching from the ceiling. As soon as the arrow hit the target, she turned Odysseus’ rags back into armour. ‘I am Odysseus,’ he cried, taking another arrow. ‘I have come back for my revenge.’ And he shot a suitor dead. Telemachus drew his sword and ran to help his father. The suitors ran to escape but Telemachus had locked the doors. The suitors fought desperately but Odysseus and Telemachus killed them all. Penelope came down from a balcony. ‘How do I know you are Odysseus?’ she asked. ‘Perhaps the gods are playing a trick on me. Perhaps they have made a beggar look just like my husband.’ Then she thought of a test. ‘Go and move the big bed into the other room,’ she said. ‘Wait,’ cried Odysseus, ‘the bed can’t be moved. I built it round a tree.’ The Penelope smiled: ‘That proves you are Odysseus. Only you know about the tree.’ And Odysseus, man of many wanderings, smiled back: ‘I am Odysseus, my faithful wife, and I have come home safely at last. And I shall tell you and my brave son, Telemachus, everything. 19