Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Global Environmental Change

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gloenvcha

Developing sustainability-oriented values: Insights from households in a trial of

plug-in hybrid electric vehicles

Jonn Axsen a,*, Kenneth S. Kurani b

a

b

School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6

Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California at Davis, 2028 Academic Surge, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 23 August 2011

Received in revised form 29 August 2012

Accepted 30 August 2012

Available online 29 September 2012

This paper explores the possibilities of consumer transitions to sustainability-oriented values. We draw

from sociological and psychological literature to develop a conceptual framework that reflexively links

an individual’s values and self-concept to their behaviors. We inductively explore the consideration, and

in some cases development, of sustainability-oriented values in a small number of narrative accounts of

peoples’ encounter with a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle during a multi-week trial. Because a plug-in

hybrid vehicle substitutes electricity for gasoline, it is a technology that potentially symbolizes

sustainability-oriented values. We classify participating households according to Schwartz’s 10

motivation types, where households associate sustainability with different motivations, namely

benevolence, universalism or self-direction. We categorize households into three groups: those that

demonstrate no interests in sustainability-oriented values, those that demonstrate interest in

developing such values during their plug-in hybrid vehicle demonstration experience, and those that

were already committed to sustainability-oriented values and behaviors. We observe that households

open to change are more likely to develop sustainability-oriented values if: (i) their self-concept is open

to change (liminal), either as a temporary transitional state or sustained as a value, (ii) they associate

sustainability with broader motivational values that are already central to their self-concept, in this case

benevolence, universalism or self-direction, and (iii) they experience positive social support for new,

sustainability-oriented values within their social networks. Our exploratory findings imply that

sustainability-oriented values can be developed in households who did not previously express them.

Value change opens new possibilities for sustainable consumer behavior, practices, and policy.

ß 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Sustainability

Values

Consumer behavior

Plug-in hybrid vehicle

Narrative

1. Introduction

This paper explores the potential for consumer transitions to

sustainability-oriented values and behaviors. Following the lead of

values researchers in psychology (Schwartz, 1994; Schwartz and

Bilsky, 1987), we take values to be stable, though not immutable,

personally held beliefs that guide behavior and perceptions across

a variety of situations. By behavior, we mean conscious actions as

well as routinized practices. Thus, ‘‘sustainability-oriented values’’

refers to any durable motivations that guide a person to enact

behaviors that are perceived as supporting sustainability goals. The

framing of these values and goals will differ across individuals,

social groups and cultures.

A widespread transition to sustainability-oriented values

could accelerate and broaden the uptake of sustainable behaviors.

Values and values change also relate to environmental policy;

* Corresponding author. Present address: 904 Britton Drive, Port Moody, BC,

Canada V3H 3S5. Tel.: +1 778 782 9365; fax: +1 778 782 4683.

E-mail address: jaxsen@sfu.ca (J. Axsen).

0959-3780/$ – see front matter ß 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.08.002

sustainability-oriented values could help garner support for (or

avoid resistance to) policy enactment (Huijts et al., 2012), and

values may shift as a result of the enactment of new policy (Axsen

et al., 2009; Bardi and Goodwin, 2011). Context-shaping policies

are needed to facilitate transitions to low-carbon societies, e.g.,

regulating vehicle manufacturers or mandating urban density,

which will inevitably change individual behaviors and perceptions,

e.g., using new vehicle technologies or taking up cycling and

walking. Such shifts in behaviors, and enactment of the policy

itself, can shape the values held by individuals. If the values people

hold can change, policy makers must understand the dynamics of

consumer (and voter) values in order to design policy that is

feasible and effective in the long run (Norton et al., 1998)—

particularly for policies that directly affect consumers.

We focus this paper on values because they are by definition more

durable and consistent than attitudes or norms—and thus more

likely linked to durable and consistent shifts in consumer behavior.

However, the role of values and other antecedents of behavior are

variously conceived; we provide several selected definitions in

Table 1. Economists model aggregated consumer utility functions for

different products, e.g., Train (1980), but do not comment on the

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

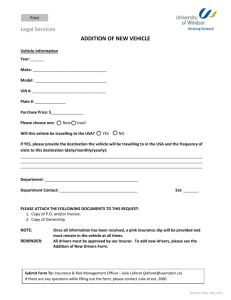

Table 1

Selected definitions of several potential antecedents to behavior.

Concept

Selected definition

Source

Preference

Consumer tastes for products (or their

attributes) given their budget level

Evaluation of an object, event or

behavior

An individual’s perception of self and

how they fit into the modern world,

which is socially negotiated over time

and across social contexts

Perceptions of what behavior is

common (descriptive norms) or socially

expected or desirable (injunctive

norms)

Personally held concepts that transcend

specific situations or objects and guide

behavior and perceptions

Jackson (2005)

Attitude

Self-concept

(identity)

Norm

Value

Ajzen (1991)

Giddens (1991)

Cialdini (2003)

Schwartz (1994)

origins and dynamics of preferences that underlie utility functions

and have had little to say about values (Jackson, 2005). Models from

social psychology represent consumer attitudes as behavioral

precursors. Multiple iterative elaborations of attitude-behavior

models have inserted the concept of intentions between attitude

and behavior, and added ‘‘beliefs’’ and ‘‘evaluations’’ as antecedents

to attitudes, norms as antecedents to intentions (Ajzen and Fishbein,

1980; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), and ‘‘perceived behavioral control’’

as a precursor to norms, intentions, and behavior (Ajzen, 1991).

However, consistent findings of attitude-behavior gaps suggest that

other factors and processes need be addressed (Gill et al., 1986;

Oskamp et al., 1991; Scott and Willits, 1994). Other behavioral

models have integrated values as behavioral antecedents (Schwartz,

1994; Stern et al., 1995), but use of terminology varies. Values are

regularly conflated with other concepts (Hitlin and Piliavin, 2004),

perhaps because values both influence and are influenced by

behavior (Jackson, 2005). Although research suggests a strong link

between sustainability-oriented behaviors and values, little is

known about the processes of value change (Dietz et al., 2005).

In this study we seek to understand how consumers’ relate their

values to their behaviors and assessments of a technology potentially

perceived as being sustainability-oriented. A methodological contribution is our use of in-depth, semi-structured interviews as part of a

‘‘behavioral trial,’’ whereas previous value research has relied

primarily on surveys or experiments (Dietz et al., 2005). We draw

from narrative accounts constructed from repeated interviews with

participants in a plug-in hybrid vehicle demonstration project in

northern California. Participating households drove a plug-in hybrid

vehicle as part of their household fleet of cars for four weeks.

Previously, we utilized these data to explore processes of interpersonal influence in car buyers’ assessments of the vehicle (Axsen and

Kurani, 2011, 2012a). Here we draw from over 70 h of interviews to

inductively learn about participant framing of sustainabilityoriented values in the context of a hypothetical purchase of a

plug-in hybrid vehicle and how such values may develop.

Next, we briefly survey relevant literature to build a conceptual

framework then apply it to the participant narratives. We note that

the limited sample size and particular context of this exploratory

study may limit the generalizability of our specific findings.

However, our results can be used to reconsider conceptualizations

of values and value change, and generate hypotheses for future

research.

2. Values and dynamics

2.1. Insights from psychology: categorizing values

Two thorough review papers outline the complexity and

confusion surrounding values. Dietz et al. (2005) start with a

71

New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary definitions of values: the

worth of a thing; liking for a thing; or, ‘‘principles of moral

standards of a person or social groups, the generally accepted or

personally held judgment of what is valuable and important in life’’

(p. 339). They go on to add that values are different than

preferences, beliefs (understandings of the world), or roles

(patterns of behavior across social situations). Hitlin and Piliavin

(2004) also attempt to explain values by what they are not; values

are more abstract than attitudes, more controllable than personality traits, less context-dependent than norms, and less biological

than needs. We apply a definition similar to that provided by

Schwartz and Bilsky’s (1987): values are personally-held concepts

that transcend specific situations or objects and guide behavior

and perceptions.

Schwartz (1994) provides one of the most widely cited value

frameworks. At the broadest level, values can be categorized by

two dimensions: self-enhancement versus self-transcendence and

conservation (or tradition) versus openness to change. Schwartz

maps ten ‘‘motivational types’’ (Table 2) onto these two dimensions. Finally, 56 values are mapped onto the ten motivational

types using empirical data from 44 countries. For example, the

value of ‘‘wealth’’ is associated with the motivational type ‘‘power’’

which is aligned with high ‘‘self-enhancement.’’

Schwartz (1994) did not explicitly include sustainabilityoriented values; the value of environmental protection (a related

but more specific value) was found to fit within the ‘‘universalism’’

motivational type, which corresponds with high self-transcendence and openness to change. Urien and Kilbourne (2011) have

linked sustainability-oriented behaviors to a lack of self-enhancement values such as achievement and power. However, we suspect

that sustainability-oriented values and behaviors could possibly

align with a wider variety of motivation types; we speculate on

such alignment using Schwartz’s ten motivation types in the third

column of Table 2. For example, sustainability could be associated

with benevolence (wanting to reduce environmental impacts on

the local community) and universalism (avoiding global impacts

on people and ecosystems). Engaging in sustainable behaviors

could also be framed as a challenge and thus be linked to values of

achievement and self-direction. In other words, two different

individuals may have very different motivations for taking on

sustainability-oriented values and behaviors, and one person may

be driven by multiple motives. However, because some of these

values may conflict with one another, one person would not likely

subscribe to all the motivations in Table 2.

Other researchers have developed various schemas to relate

value types to pro-environmental and pro-sustainability behaviors. Schultz (2000, 2001) and Stern and Dietz (1994) identify

three broad value classes for environmental concern: self-interest

or egoistic (concern for self and kin), humanistic altruism (concern

for other humans), and biospheric altruism (concern for other

species). A fourth, suggested by Kempton et al.’s (1995) in-depth

exploration of American environmental values, is religion and

spirituality—though this has received less attention in the

literature. Such models of pro-environmental behavior typically

portray the effect of values as mediated by other antecedents of

behavior. For example, Stern et al.’s (1999) value-belief-norms

model depicts how an individual’s ascription to egoistic, altruistic

or biospheric values influences their beliefs about the environment, which in turn influences their awareness of consequences

and feelings of responsibility. These beliefs are represented to in

turn influence their personal norms and finally their behavior.

Most psychology-based models represent an individual’s values

as static (Bardi et al., 2009). The few psychology-based insights

offered into value change are largely speculative. For example,

Rokeach (1968) suggested that values would change when an

individual realized that their existing values were inconsistent.

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

72

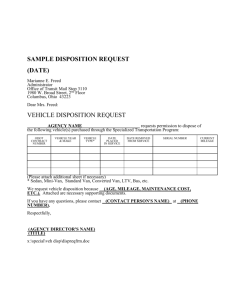

Table 2

Schwartz’s ten motivational types of values and possible links to sustainability.

Type

Definition (Schwartz, 1994)

Possible motives to adopt or support ‘‘sustainable’’ behaviors

1. Power

‘‘Social status and prestige, control or dominance over people and

resources.’’

‘‘Personal success through demonstrating competence according to

social standard.’’

‘‘Pleasure and sensuous gratification for oneself.’’

‘‘Excitement, novelty and challenge in life.’’

‘‘Independent thought and action—choosing, creating and exploring.’’

‘‘Understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection for the welfare

of all people and for nature.’’

‘‘Preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one

is in frequent personal contact.’’

‘‘Respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that

traditional culture or religion provide.’’

‘‘Restraint of actions, inclinations, and impulses likely to upset or harm

others and violate social expectations or norms.’’

‘‘Safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and of self.’’

Controlling others’ resource use

2. Achievement

3.

4.

5.

6.

Hedonism

Stimulation

Self-direction

Universalism

7. Benevolence

8. Tradition

9. Conformity

10. Security

Hitlin and Piliavin (2004) draw from attitude change research

(e.g., Petty and Cacipoppo, 1986) to hypothesize that because

values are inherently relevant to the individual, value change is

likely to occur through active processing and reflection (central

route) rather than more automated peripheral routes observed for

non-relevant attitudes. Bardi et al. (2009) use Schwartz’s 10

motivation, two-dimensional framework to explore value change

across repeated surveys of the same samples. They find that value

change, defined as changes in importance or ranking of a given

value, is more likely to occur among respondents that experience

significant life changes in the inter-survey period. Values are also

thought to be changeable through engagement with new social

groups, through changes in behavior, e.g., following a new law,

social norm, or employment role, or through direct persuasion

(Bardi and Goodwin, 2011).

2.2. Insights from social theory: reflexivity, self-concept and values

With that background from more ‘‘individualist’’ perspectives,

we look for further insights on value change from social theory. We

are motivated by prior findings of the importance of interpersonal

interactions in shaping attitudes toward pro-environmental

technologies and in consideration of sustainability-oriented

behaviors more broadly (Axsen and Kurani, 2012a,b). And as

noted in the previous summary of literature from psychology,

changes in values have been linked to processes of social influence

and changes in social expectations (Bardi and Goodwin, 2011).

To contextualize social processes of value change, we first

orient values as a component of an individual’s self-concept or

identity—their perceptions of who they are. Following Brewer and

Roccas (2001) and Hitlin (2003), we conceptualize values as the

core or ‘‘cohesive force’’ within personal self-concept. Although

research linking values and self-concept is limited (Hitlin and

Piliavin, 2004), preliminary research suggests that identity can

play a stronger role in sustainable behavior than attitudes (Stets

and Biga, 2003), that environmental values are linked to natureoriented identity (Schultz et al., 2004), and that only values central

to self-concept will influence sustainable behavior (Verplanken

and Holland, 2002). Thus, we expect there to be some correspondence between sustainability-oriented identities, values, and

behaviors.

Framing values within self-concept is also useful because there

has been relatively more discussion on the dynamics and social

negotiation of self-concept or identity (Burke, 2006; Deaux and

Martin, 2003; Giddens, 1991). In particular, Giddens (1991)

explains how individuals must actively create their self-concept,

taking on an ongoing, dynamic ‘‘reflexive project’’ to define and

Setting and accomplishing energy efficiency goals

Enjoying sustainable behaviors in themselves

Trying novel behaviors and technologies

Becoming independent of a ‘‘polluting’’ system

Preserving the biosphere for all humans and animals

Preserving environment for family and others in social

network, community or nation

Adhering to cultural values by preserving ecosystems

Following sustainable behaviors demonstrated by others

Minimizing personal risk of environmental collapse

express oneself. If an individual’s behavior is shaped by their

efforts to establish and develop a self-concept, particular behaviors

are grouped into lifestyle: packages of behaviors (conscious and

routinized) that the individual (and their reference group)

associates with their self-concept. A given individual may

subscribe to several lifestyles across different reference groups,

e.g., family, co-workers and recreational friends. This characterization of identity and lifestyle has been applied to sustainable

consumption behaviors (Spaargaren, 2003; Spaargaren and Van

Vliet, 2000), and environmentalists’ negotiation of behavior amidst

conflicting agendas (Evans and Abrahamse, 2009). We note that in

addition to our present use of self-concept, there are various

alternative conceptualizations of identity including definitions

based on social roles such as gender, race, and nationality (Burke

and Tully, 1977; Stryker, 1980, 1987)—we presently do not follow

role-based definitions, but acknowledge the potential importance

of roles among other social factors.

In the context of Giddens’ (1991) approach, we conceptualize

values as the ‘‘cohesive force within’’ self-concept (Hitlin, 2003);

that is, an individual’s self-concept builds around multiple highpriority or core values (or motivations). As noted in the previous

section, an individual is not likely to subscribe to all of Schwartz’s

(1994) ten motivation categories or 56 values. Thus, an individual’s

self-concept is likely to be more firmly based on only a subset of

such values that are of high priority to the individual. Further,

Giddens’ (1991) notion of reflexivity is based on the dynamics of

expression and negotiation of one’s self-concept, implying that the

core values that make up this self-concept can be developed or

changed. Here, by value change we mean changing the importance

or prioritization of values as they relate to self-concept.

To further aid this discussion, we consider the concept of

liminality—how open an individual’s self-concept and values are to

change. Liminality is related to Schwartz’s ‘‘openness to change’’

dimension of values, but is a broader concept. According to Turner

(1969), liminality is a state characterized by ‘‘ambiguous and

indeterminate attributes’’ either through a temporary transition or

sustained conditions. Thus liminality could be sustained through

the embodiment of values Schwartz identifies with openness to

change. But there are many other possible sources of liminality. At

a societal level, new behaviors and norms can emerge during a

liminal period (Swidler, 1986). Though less research has been

conducted on understanding liminality at the individual level, we

speculate that liminality is heightened at transitional points in

one’s life, such as changing relationship status, changing jobs, or

moving residence. As noted in the previous section, the importance

of life changes to value change is already being discovered in

studies of social psychology (Bardi et al., 2009). Liminality may also

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

73

change in response to experimenting with that behavior.

Therefore, we sought to identify participants from across a

spectrum of prior values, i.e., some do not ascribe to sustainability-oriented values, some are committed to such values, and of

primary interest, some are considering making a transition toward

sustainability-oriented values.

To structure our exploration, we presume that values can

change and that values change can occur, in part, through changes

in behavior. Drawing from the above discussion of value change

and identity, we utilize the following conceptual framework

linking sustainability-oriented values to sustainable practices:

be supported by a household having more access to resources such

as time and money (or income) to afford experimentation in

lifestyle behaviors.

Giddens’ framework implies that not only can values (and selfconcept) serve to guide behavior, but behavior can also be means of

trialing and socially learning about one’s values. For example,

engagement in a sustainable behavior, e.g., driving a plug-in hybrid

vehicle, could be a trial of a more fundamental shift toward

sustainability-oriented values and self-concept. Experimentation

with a new behavior associated with a new value may cause the

individual to solidify, modify, or reverse their commitment to the

value and related lifestyle.

We distinguish Giddens’ perspective on lifestyle and our

present focus on values from practice theory. Practice theory also

views sustainable consumption as practices, but defines practices

as the routinization of related bodily and mental activities that are

socially constructed and reflexively refined (Reckwitz, 2002;

Ropke, 2009). Practices, such as driving automobiles, are constructed and sustained by the individual practitioners (Shove,

2010)—by engaging in the practice, the individual normalizes and

sustains it. For example, Shove (2004) uses practice theory to

explain the co-evolution of air-conditioning and food refrigeration

with increasing cultural standards and expectations of comfort.

Practice theory is useful for the description of society becoming

locked-in to particular patterns of consumption, and emphasizes

the challenges of overcoming such normative behaviors to increase

the uptake of more sustainable practices. The approach we take

looks at processes of behavioral lock-in versus change and

development at the household level through the examination of

values expressed by household members. We use the term

‘‘practice’’ to refer to any ongoing behavior, rather than in the

more formal definitions provided by practice theory.

Regarding the fourth and fifth points, sustainability-oriented

values might be manifest by driving an electric-drive vehicle, e.g., a

plug-in hybrid vehicle. Driving an electric-drive vehicle can be

both an expression of sustainability-oriented value and a trial that

informs, reinforces or negates the individual’s commitment to that

value.

2.3. Conceptual framework of value change

3. Methodology

The concept of ‘‘sustainability-oriented’’ values is an intentionally broad concept that may include a variety of proenvironmental and pro-societal motivations. We have reviewed

several models of and perspectives on value categories that could

have guided the statement of specific hypotheses and experimental designs. However, we use an inductive, semi-structured

interview methodology to learn whether and how participants

discuss and express sustainability-oriented values. In this sense,

having convened conversations with our participants, we listened

for whether their narratives convey values that are attached to a

particular sustainability-oriented behavior and processes of value

3.1. Sample and context

1. An individual constructs their self-concept around one or more

core value(s).

2. An individual’s self-concept is developed and maintained in a

social context.

3. Sustainability-oriented values are more open to development or

change if the individual is in a liminal state, which can be

transitional or sustained.

4. Core values and self-concept are manifest as lifestyle: packages

of behaviors that are shaped by, and are expressions of, a

particular value or set of values.

5. Values, self-concept and construction of and engagement in

lifestyle behaviors are reflexively related—influence iteratively

flows in multiple directions.

To explore understandings of sustainability-oriented values

and processes of value change, we draw from 10 households (18

individuals) who participated in a plug-in hybrid vehicle

demonstration project conducted at the University of California,

Davis (full methodology detailed in Axsen (2010)). Participating

households resided in the Sacramento, California area, and did not

receive any incentives other than the opportunity to drive a plug-in

hybrid vehicle. The vehicle is a Toyota Prius converted to be

powered in part from an additional 5 kWh battery recharged using

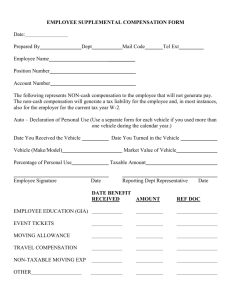

Table 3

Characteristics of 10 participating households (18 participants).

Surname

First name

Dominant lifestyle(s)

Household income

Age

Earhart

Fort

Betty

Brett

Julie

Craig

Siobhan

Rupert

Amy

Adam

Katrina

Ethel

Ed

Silvia

Larry

Cheryl

Darren

Pat

Melissa

Billy

Career

Social, recreation

Education, recreation

Environment, technology, social

Environment, technology, social

Social (family)

Social (family)

Social (family), technology

Education, social (family)

Social (family)

Social (family), career, technology

Social (family), career

Social (family), environment, technology

Social (family), environment, technology

Career, social (family)

Career, social (family)

Student, social

Recreation, social

$50–59k

$100–124k

30s

40s

20s

40s

40s

40s

40s

60s

30s

50s

30s

30s

40s

30s

50s

50s

20s

40s

McAdam

Noel

Petrov

Potter

Ranchero

Rhode

Stashe

Woods

>$150k

$80–89k

$40–49k

>$150k

$100–124k

>$150k

$100–124k

$100–124k

74

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

any 110-V outlet. Each household’s trial lasted four to six weeks.

We expected the use of this vehicle to stimulate household

consideration of sustainability-oriented values for at least two

reasons. First, electric-drive vehicles, and in particular the Toyota

Prius, are typically perceived as being pro-environmental symbols

in California (Heffner et al., 2007). Second, automobiles in general

can by highly symbolic objects (Steg, 2005), and automobile use is

typically considered to be a conspicuous act with strong relations

to personal identity (Shove and Warde, 2002).

Table 3 details the sample by age and income; all names are

pseudonyms. Although households were drawn from one region in

northern California, the range of socio-economic, demographic and

attitudinal attributes among participants approximate those of a

representative, U.S.-wide sample of new vehicle buyers (Axsen and

Kurani, 2009). We intentionally selected this sub-sample from a

broader pool of households in an attempt to include households

with different social and demographic characteristics. Table 3 also

classifies each individual by one or more lifestyle types they

demonstrated to researchers during the four to five interviews that

took place. We categorize each household according six lifestyle

types derived from a survey of households and pro-environmental

behavior (Axsen et al., 2012).

3.2. Semi-structured interviews

Our interview methodology is ethnographic in the sense

outlined by Atkinson and Hammersley (1994). We explore

research questions rather than testing specific hypotheses, work

with uncoded data, investigate a limited number of cases, and

interpret participants’ verbal description in effort to understand

their behavior. However, our approach is better described as semistructured because we included structured exercises in the

interviews, which can serve to create a more efficient method

overall (McCracken, 1988). In open-ended components we

developed a natural dialog with participants, and sought to

establish trust and rapport. Though a prepared list of topics

provided some structure to the interviews, the researcher was free

to pursue and explore new insights that arose during the interview,

even if it required temporary departure from that list. Each

interview lasted from 1 to 2 h, with each household participating in

four to five interviews over their four to six-week trial of the plugin hybrid vehicle. Each interview was conducted in the respondents’ home in effort to create as comfortable and neutral a social

encounter as possible for the household.

Prior to their trial of the plug-in hybrid vehicle, the households’

first interview elicited their vehicle purchase histories, future

vehicle purchase intentions (if any) and expectations of the plug-in

hybrid vehicle (if any)—this information helped to construct the

beginning of the households’ narratives as well as providing initial

context for demonstrating values and motivations. Researchers

also collected information about the household’s social network

using a method described by Hogan et al. (2007). This social

network information informed a related project on social

influence, summarized by Axsen and Kurani (2012a), though this

information is also entirely relevant for the present analysis of

value change given the socially constructed nature of values in our

conceptual framework (Section 2.3). During their vehicle trial, each

household completed several tasks. Bi-weekly interviews elicited

information about the household’s ongoing experiences with the

vehicle. Participants completed a two-part web-based survey that

had been previously completed by a large, representative U.S.

sample (Axsen and Kurani, 2009). Participants also completed a

social episode diary, reporting verbal or non-verbal interactions

with other people relating to the plug-in hybrid vehicle; the

instrument and results are summarized by Axsen and Kurani

(2011). The final interview elicited the household’s narrative of

their overall experience with the plug-in hybrid vehicle, including

use of the vehicle and learning and assessment of the vehicle.

Participants also completed an ‘‘influence’’ ranking exercise to

communicate which experiences (with the vehicle, social, or

otherwise) had more influence on their perceptions of plug-in

hybrid vehicle technology.

3.3. Narrative construction

Eliciting data in narrative form can be a highly effective way to

understand subjective experience, challenge research preconceptions and cultivate new perspectives on social phenomena

(Burnett, 1991). Narratives can be a form of ‘‘thick’’ description

that illuminate behavioral patterns that might be missed by more

tightly focused, deductive research approaches (Geertz, 1973).

Further, a narrative approach is consistent with Giddens’ (1991)

reflexivity perspective (summarized in Section 2.2), where

individuals come to understand themselves by linking their past,

present and future into a cohesive storyline. Thus, the constructing

and telling of narratives may help discover how an individual

reflexively relates their plug-in hybrid vehicle experience to their

values and potentially how the individual may consider and

develop new values.

A well-formed narrative includes: a goal-state; goal-related,

chronological events; a logical, causal flow of events; and,

demarcation signs such as ‘‘at first’’ and ‘‘by the end’’ (Burnett,

1991; Gergen and Gergen, 1987). Of course, eliciting meaningful,

coherent narratives can be challenging. This is one reason we also

employed structured exercises to provide context for the

participant’s story—researchers utilized relevant results from

these exercises to inform the constructed narratives. Further,

the order and wording of the final interview questionnaire

intentionally guided a narrative response: it was structured

around the goal-state of their plug-in hybrid vehicle assessment,

prompts were ordered chronologically (beginning with the

participant’s initial expectations, moving to their vehicle trial

experiences, then concluding with their assessment), and an

influence ranking exercise elicited their perceptions of causality

between their experiences and assessment.

By constructing narratives for each household, the researchers

serve as instruments themselves (McCracken, 1988). Researchers

reviewed interview recordings and complete transcripts of each

interview and produced a summary relating to value change, then

integrated these summaries with information from their online

survey responses and structured exercises. We analyzed narratives

from all 10 households, and looked for patterns relating to the

dynamics of values, self-concept and behavior. In particular, we

look for their understanding of and commitment to sustainabilityoriented values and behavior and how these values may develop or

change in some cases. We summarize several illustrative

narratives in the next section.

4. Results

4.1. Framing of sustainability-oriented values

Our conceptual framework (Section 2.3) and semi-structured

method allowed participants to frame their perceptions of

sustainability-oriented behaviors and values in their own terminology (if they had anything to say about sustainability at all). That

is, we did not impose analytic categories at the time of the

interviews. However, we do impose such a structure to frame the

results (and summaries of narratives) using what we have learned.

To start, we found that participants’ engagement with sustainability-oriented values did not correspond with the altruistic,

biospheric and spiritual distinctions promulgated by prior

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

researchers (Schultz, 2001; Stern et al., 1999), or Schwartz’s (1994)

mapping of environmental protection onto universalist motivations. Rather, we found Schwartz’s broader framework of 10

motivational types a useful starting point for describing participants’ ‘‘core’’ values (which form their self-concepts). Through our

methodology of narrative construction, participants connected

commitment to a future plug-in hybrid vehicle purchase to

sustainability through three different core values. As we will

discuss, in addition to universalism, participants also linked

sustainability-oriented values with the core values of benevolence,

i.e., benefitting socially closer individuals such as friends and

family, and self-direction, i.e., providing a challenge that involved

individualistic learning and development. Sustainability did not

form its own core value, but rather fit in with other, higher level

motivations, i.e., Schwartz’s ten motivational types.

We differentiate the ten households into three categories

according to their commitment or openness to sustainabilityoriented values in Table 4. First are households that are not

presently motivated by sustainability-oriented values and demonstrate no interest in developing such values. Second are those

open to exploring sustainability-oriented values. Third are those

previously committed to sustainability-oriented values. Each

household differed in terms of which core values were demonstrated via their narrative of experience and social interactions

pertaining to the plug-in hybrid vehicle trial.

Looking across these households, we identify three conditions

associated with those in the second group, i.e., those open to the

development of new, sustainability-oriented values. These households were found to develop or strengthen their commitment to

sustainability-oriented values by the end of their plug-in hybrid

vehicle trial when they start with a moderately to highly liminal

self-concept, come to associate sustainability with one of their

existing core values, and experience positive social support for the

new lifestyle practice and values.

Next we utilize household narratives to illustrate these

conditions. We summarize illustrative narratives from the

participant groups that did not demonstrate interest in value

change, and then elaborate on all four households exploring

sustainability-oriented values. By focusing on these households we

garner more understanding of how sustainability-oriented values

can be developed.

4.2. Households committed to private or sustainability-oriented

values

Households in the first and third groups maintained their initial

values over the course of their plug-in hybrid vehicle trial—they

75

either demonstrated no interest in developing sustainabilityoriented values or were already committed to such values.

First, the Noels, the Petrovs, Betty Earhart and the Stashes each

began and ended their plug-in hybrid vehicle trial with no interest

in sustainability-oriented values. They framed the practice of

driving the vehicle according to self-enhancement values such

financial savings, safety and status. Consider Adam Petrov as an

example. He is a retired maintenance supervisor in his sixties who

spends most of his time doing handy-man ‘‘small jobs’’ for friends

and acquaintances. He primarily assessed the vehicle based on the

performance of the engine and battery as he would assess one of

his power tools. He demonstrated strong commitment to the

traditions of his family, church and career, and benevolence in

sharing his skills with those socially close to him. However, Adam

demonstrated no interest in or understanding of sustainabilityoriented values and did not interpret the plug-in hybrid vehicle

according to sustainability or benevolence. Further, the Petrovs

were surprised to find the plug-in hybrid vehicle stimulated little

interest in their social network, which itself consists of likeminded individuals who also emphasize traditional values. Any

vehicle-related conversations that did occur only addressed

technical aspects of the vehicle such as fuel costs and handling.

By the end of their trial the Petrovs lacked interest, openness and

social support to consider a transition to sustainability-oriented

values.

In contrast, the McAdams and the Rhodes began and ended

their plug-in hybrid vehicle trial with strong commitments to

sustainability-oriented values. For example, Larry and Cheryl

Rhode consider themselves to be ‘‘tree huggers’’ that have been

dedicated to sustainability-oriented practices for many years—

such values are well integrated into their lifestyle and social

network. They are eager to explain that they practice organic

gardening, use only compact fluorescent light bulbs, and send their

son to a preschool that espouses environmental values and

includes special classes on environmentally friendly technologies.

Larry in particular is highly competitive in his career as well as his

efforts to achieve high fuel economy in his own hybrid vehicle and

in the plug-in hybrid vehicle trial he was happy to ‘‘beat the fleet’’

of other plug-in hybrid vehicle drivers’ fuel economy. His

commitment to sustainability-oriented practices is motivated by

strong values of achievement and self-direction. The Rhodes also

have many sustainability-oriented friends and acquaintances, and

Larry frequently goes out of his way to tell others about his hybrid

car and the plug-in hybrid vehicle during his trial as part of ‘‘getting

the word out.’’ In short, the Rhodes were already engaged in a

sustainability-oriented lifestyle, supported by like-minded friends

and acquaintances. The practice of driving the plug-in hybrid

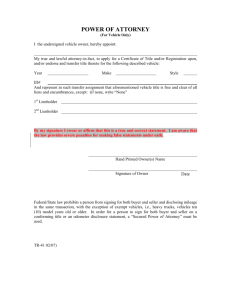

Table 4

Three patterns of value orientation.

Household (by interest in

sustainability-oriented values

1. No interest:

Betty Earhart

The Noels

The Petrovs

The Stashes

Melissa Stashe

2. Exploring:

The Forts

Ethel Potter

The Rancheros

Billy Woods

3. Committed:

The McAdams

The Rhodes

Demonstrated core values

(Schwartz’s motivation type)

Sustainability

associated with:

Liminality

Sustainable-oriented values

Social network support

Acceptance of value

Achievement

Tradition, conformity

Tradition, benevolence

Security

Conformity

Universalism

–

–

–

–

Mod

Low

Mod

Low

High

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

No

Hedonism, security, benevolence,

self-direction

Self-direction, stimulation

Security, benevolence

Stimulation, conformity

Benevolence

High

Yes

Yes

Universalism, self-direction

Benevolence

Benevolence

High

Mod

High

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

No

Benevolence

Achievement, self-direction

Benevolence

Self-direction

Low

Low

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

76

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

vehicle fit their existing core values and their existing commitment

to sustainability-oriented values in particular.

4.3. Households open to sustainability-oriented values

Billy Woods, the Rancheros, Ethel Potter, and the Fortes each

exhibited liminality—openness to shifting their self-concepts and

develop new, sustainability-oriented core values. However, in only

two of these four households did this openness to value change at

the time of their plug-in hybrid vehicle trial end with the

development of new sustainability-oriented values. The following

narrative summaries illustrate why, following the three conditions

identified above.

4.3.1. Why did Billy Woods reject sustainability-oriented values?

Billy began his vehicle trial in a liminal state. He was recently

divorced and had a new girlfriend. He tries and takes part in many

different recreational activities. He has friends and casual

acquaintances from a variety of social groups, including coworkers,

golfing friends, and friends from bars and nightclubs. He earns a

relatively high income and has the flexibility to work from home or

his office. Billy was not committed to a particular routine, set of

activities, or social group—he was dabbling in a variety of practices

across different social groups.

Billy is highly motivated by stimulation values—seeking novel

experiences—as well as conformity, where he is constantly seeking

to understand the norms of his social networks so that he can align

with them. Billy’s stimulation and conformity-based values are in

part what guide him to consider sustainability-oriented values in the

first place. He quickly understands how an electric-drive vehicle is

seen as an environmental symbol, and he wants to learn if this

symbol (that is novel to him) might fit with his self-concept and

social reference groups. Prior to the vehicle trial, Billy had few

thoughts of sustainability; he did not consider sustainabilityoriented values when engaging in activities, and he did not devote

any significant time or resources to sustainable practices. His

conceptualization of sustainability is linked to vague ideas such as

‘‘overall cleaner, livable cities’’ and framed more by benevolence

rather than universalism (‘‘I focus on my own country. . .let [others]

worry about their own’’). However, during his trial he briefly

engaged with the sustainability aspects of the plug-in hybrid vehicle.

Billy’s ultimate rejection of sustainability-oriented values

results from social feedback. Billy was disappointed to find mixed

responses to the plug-in hybrid vehicle across his social groups.

Many of his relatives and acquaintances seemed disinterested in

the vehicle altogether or were unable to grasp what it is. Of the

friends and acquaintances that were interested, most focused on

technical functions or performance. Billy intentionally mentions

sustainability concerns with one particularly influential group of

coworkers, asking them: ‘‘Why would you buy a hybrid. . .mainly to

protect the environment or from a consumer standpoint?’’ When

his coworkers declare a lack of support for the environment, Billy

concurs and drops further consideration, saying: ‘‘To buy it just to

protect the environment is probably not something I’d do at this

time.’’ Thus, while Billy’s liminality makes him receptive to

experimenting with the car, exploring the values associated with it,

and the question of a transition to sustainability-oriented values,

he abandons this consideration when he sees an apparent lack of

support and interest in his social network. While he associated his

vague concepts of sustainability with the motivation of benevolence, the motivation to conform to others’ perspectives proved

more important the end.

4.3.2. Why did the Rancheros reject sustainability-oriented values?

Ed and Silvia Ranchero’s self-concepts were liminal in a

transitional sense—they were moving through a phase of opening

some new lifestyles and closing off others. Their recent marriage

and new child were shifting their priorities. Ed had had to change

from his powerful pickup truck to buying a family sedan: ‘‘I need a

four-door to get in and out easily. . .to put my kid in something

that’s safe. . .reliable.’’ They also became more interested in

sustainability issues through the motive of benevolence, in

particular relating to their child’s future. Ed explains:

‘‘I want to do my part in reducing global warming. . .to be more

environmentally friendly. I wanted my daughter to have

something. . .an environment that is free of pollution when

she grows up. . .that definitely became more important when

she was born. [After having a child] your focus totally changes

from being on yourself to being on somebody else.’’

Further, Ed repeatedly spoke with his wife and coworkers about

his concerns of the environmental impacts and unsustainability of

energy use.

At the same time, other aspects of the Rancheros’ self-concept

were becoming less liminal as their family patterns increasingly

centralize around their baby daughter. They emphasize security

values relating to their household; for example, the Rancheros are

too cautious (worried about leaving the car plugged in overnight)

and resource-constrained (in time and effort) to integrate regular

plug-in hybrid vehicle recharging into their daily schedule. They

state that they perceive the immediate needs and safety of their

daughter as more important than indirectly benefitting her

through long-term environmental benefits or cost savings. Silvia

becomes ‘‘paranoid’’ that the vehicle charger could start a fire, and

Ed points out that his ‘‘main concern is [his] daughter’’ although he

admits, ‘‘maybe my concern [about recharging] is without

founding.’’ Thus, the Rancheros only plug-in their plug-in hybrid

vehicle on a few occasions, and end up using much less electricity

and thus much more gasoline than they would have had they

regularly charged the vehicle.

By the end of their plug-in hybrid vehicle trial, Ed and Silvia

were surprised and ‘‘sort of disappointed’’ with how little interest

the vehicle generated among their friends and coworkers. They

expected friends and coworkers to be ‘‘hyped’’ about the vehicle,

yet most demonstrated only casual interest or none at all. Ed

notes: ‘‘I was probably expecting more people to be more open

minded about it. . .to be excited about it. . .but not everybody

thinks the same way.’’ The Rancheros explain that electric-drive

vehicles are beyond the realm of typical discussions, even about

vehicles, within their groups, and their social contacts were not

openly committed to sustainability-oriented values or behaviors.

Ed imagines that ‘‘if people were [more] excited about it. . .the

[plug-in hybrid vehicle trial] would have been a little bit

different.’’

In summary, the Rancheros volunteered for the vehicle study

during a window of time when their marriage and new child had

opened their lives to many changes. The Rancheros’ interest and

understanding could have supported a shift to sustainabilityoriented values. However, the conflict between increasing familyoriented values (particularly the security of their daughter) with

the new perceived risk posed by the vehicle, plus a lack of

countervailing social support quashed any serious commitment to

value change.

4.3.3. Why did Ethel develop sustainability-oriented values?

Ethel’s self-concept became increasingly liminal as each of her

eight children grew up and moved out, and as her household

income and financial stability improved. For much of her life she

has been interested in new scientific breakthroughs and technologies, and recently became more concerned about energy issues

such as oil dependence and emissions: ‘‘We’re such pigs with

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

energy.’’ She associates her sustainability concerns with a

universal perspective: ‘‘When you look at the rest of the

world. . .there [are] some simple things you can do. We’re just

living the way we live, gobbling up energy. . .it just doesn’t seem

right.’’ Prior to her plug-in hybrid vehicle trial, Ethel’s interest in

sustainability issues prompted her to consider similar technologies and talk to others about their effectiveness. She had heard

about waiting lists for hybrid vehicles, and one coworker had

warned her about battery toxicity and electricity generation

impacts for electric-powered vehicles. Ethel’s core values include

self-direction and stimulation—she feels she is now better able to

realize the latter value because her increasing disposable income

gives her the ‘‘luxury’’ to more actively consider and try out new

behaviors such as adopting solar panels and electric-drive

vehicles.

During her trial, Ethel is disappointed by the lack of broad

support across her social network—‘‘it’s amazing how little people

notice [the vehicle]. . .especially the fact that it’s a plug in.’’

However, she felt inspired by the ‘‘interest, enthusiasm and

encouragement’’ offered by several key friends and acquaintances,

such as two of her favorite daughters, and a repairman that visits

her home. Ethel likes how the vehicle brought her into a contact

with a new friend from her craft class, where the technology served

as a ‘‘way to talk to her more. . .we’re getting to know each

other. . .we have a lot in common.’’ By trying the plug-in hybrid

vehicle, Ethel became better able to articulate her own values and

contrast them with the motives of others—such as her boss’s

purchase of a sports car:

‘‘For the first time I saw her car today. . .it just to me is so typical.

I was looking at that car thinking, do I feel jealous? No, at this

time in my life, I’d rather be making an impact in some way, a

positive impact rather than driving some gas guzzling [sports

car]. Maybe 10 years ago I would have thought, ‘Oh, I want that

car.’ [Now] I just want a car that makes sense. . .and actually

may make a difference.’’

Such support and reflection helped Ethel to solidify her initial

interests in sustainability-oriented values, empowering her to take

additional actions and make commitments. For example, during

her vehicle trial she committed to install solar panels on her roof

and she was excited about one day being able to use the generated

electricity to power a plug-in vehicle. In addition to being an act

motivated by universalism, the development of sustainabilityoriented values was consistent with Ethel’s motives of selfdirection.

4.3.4. Why do the Forts develop sustainability-oriented values?

The Forts sustain a state of lifestyle liminality. Brett, Selena, and

their two children form a tight family unit; their social circles

closely overlap, and they typically consult only one another

regarding vehicle purchases and other issues—potentially resulting

from a lack of proximate extended family. This insular social

arrangement seems to buffer the Forts from external social

pressures.

Self-direction forms one of the Forts’ core values; they

experiment with several alternative and perhaps conflicting

motivations, including hedonism, security and benevolence. The

Forts embody hedonistic values in their ‘‘bigger is better’’ living

and recreational activities; they own and operate three large lightduty trucks and initially dreamt of an even larger one, and

regularly haul and drive dirt bikes and all-terrain vehicles for

recreation. At the same time, the Forts were increasingly shifting

toward sustainability-oriented household behaviors, such as

reducing water use and buying efficient appliances—driven by

benevolent concerns about avoiding local impacts from ‘‘smog’’

77

and ‘‘ozone depleting’’ substances. Selena has recently led their

household to become more environmentally aware in general:

‘‘We use environmentally friendly dish washing soap and laundry

soap. . .turn the shower off halfway. . .we recycle everything. . .[Selena’s] become very green over the years.’’ The Fort’s

perspective on vehicles is also heavily influenced by security

motives. After Selena twice experienced automotive accidents

where she was in a smaller car hit by a larger truck, the Forts

resolved to buy only large vehicles: ‘‘mass always wins.’’ When the

daughter, Julie, received her driver’s license the Forts bought her a

new, powerful pickup truck solely for the purpose of safety.

As a tightly knit household, the Forts explain that their most

influential social experiences occur with close family, and they

typically don’t look beyond each other when considering vehicle

purchases. Indeed, most of their conversations about the plug-in

hybrid vehicle took place with one another. Despite their

generally inward focus, Selena explains they were initially

worried about the Prius being viewed as a ‘‘weenie car’’ in other

social groups. They were surprised to find mostly positive

reinforcement by acquaintances and strangers—in particular a

hybrid-driving family that enthusiastically waved to the Forts on

the highway. The Forts were at first baffled by the experience

(which they rated as being highly influential), and tried to

understand the significance of the event:

Brett: ‘‘the wave on the freeway. . .was actually pretty cool.’’

Julie: ‘‘we don’t get waved at. . .frequently by strangers.’’

Brett: ‘‘you know, [when] you’re driving a truck. . .someone in a

[hybrid car] doesn’t normally wave at you. . .they may flip

something at you. . .but it won’t be a wave.’’

Julie: ‘‘[it was like] we would be part of the family if we had [a

hybrid vehicle].’’

Brett: ‘‘I think [this type of experience] makes you feel good

about doing something good. . .one of those feel good

moments.’’

Similarly, Julie contrasted the positive social support she

received for the plug-in hybrid vehicle, with the ‘‘dirty looks’’

she would get when driving her large pickup truck—like the ‘‘dirty

looks from vegans when you’re wearing leather.’’ When Brett and

Julie drove the plug-in hybrid vehicle, they saw the world from this

other perspective: ‘‘I have found myself looking at trucks, saying,

‘Wow, he’s taking a lot of gas.’’’

By the end of their plug-in hybrid vehicle trial, the Forts made

commitments to purchase a hybrid vehicle to strengthen their

commitment to sustainability-oriented value. The excitement of

this new commitment diminished the importance of motivations

that seemed to be of higher priority in their first interview,

including concerns about security and hedonistic goals of owning

even bigger trucks. Experiences of social support (and lack of

ridicule) served to further legitimize the Forts growing environmental interests and commitment to sustainability-oriented

values. In this validation, the Forts were not so much conforming

to the values of others, but instead finding a lack of the social

resistance they expected.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This paper set out to better understand sustainability-oriented

values and how such values can be developed. We reviewed

literature from psychology and sociology to construct a conceptual

framework to guide our empirical analysis using narratives of

participants in a plug-in hybrid vehicle (plug-in hybrid vehicle)

demonstration project. We frame values as the cohesive force of an

individual’s self-concept, and describe identity and values are

78

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

reflexively linked to behavior. These core values (and self-concept)

are socially negotiated and defined, and more prone to change

when the individual is in a liminal (transitional or open) state.

Through semi-structured data collection and narrative

analysis, we hear processes (or the lack thereof) of the formation

of sustainability-oriented values, in distinction from the formation of attitudes or preferences. Participants do express attitudes

and preferences relating to the plug-in hybrid vehicle; these

attitudes are stated in relation to the specific object, i.e., a

vehicle, and are relatively fluid as participants gain experience

with the technology over periods of four to six weeks. In contrast,

when participants talk about their concepts of sustainability,

they engage broader, relatively stable beliefs and feelings that

guide behavior across a range of situations. Participants tended

to link their concepts of sustainability with a variety of behaviors

beyond the use of the plug-in hybrid vehicle itself, such as

recycling, installing solar panels, and reducing household energy

use. These observations confirm that values are a useful

construct for observing how perceptions of sustainability relate

to behavior.

We find that participants’ expression of sustainability-oriented

values do not align with the egoistic, humanistic altruism and

biospheric altruism categories utilized by many values researchers

(Schultz, 2001; Stern and Dietz, 1994; Stern et al., 1999). Instead,

we find that sustainability-oriented values can be aligned with a

variety of core values. Schwartz’s (1994) ten general motivational

types proves useful for categorizing participant’s core values, and

how they frame sustainability-oriented values (if at all). Although

Table 2 hypothesized potential links to sustainability for each of

the ten motivation types, in this study we only observed links to

three: universalism, benevolence and self-direction. This is a more

diverse set than Schwartz’s (1994) mapping of environmental

concern solely onto universalism and more values were engaged

by our respondents who were open to values change, including

stimulation, conformity, and security. Our finding suggests other

motivational links to sustainability may be possible in other

samples and contexts, and for other sustainability-oriented

behaviors.

These narratives also yield insights into value change. We

highlight three broad conditions that facilitate the development of

sustainability-oriented values among plug-in hybrid vehicle trial

participants. Each condition relates to the reflexive relationship

between values and behavior outlined in our conceptual framework. Here we summarize these conditions with examples

observed in the vehicle demonstration study (Table 5).

First, if the household is not already committed to

sustainability-oriented values, their self-concept must be in a

liminal state to facilitate consideration of new values. Liminality

can be a temporary state of transition: Billy Woods was recently

divorced and seeking new ways to structure his life, and Ed and

Silvia Ranchero were newly married and working to understand

their priorities with a growing family. In time, an individual’s

self-concept may return to a more stable state. In other cases,

liminality can be sustained: Ethel Potter increases liminality

over a period of years as her children move out and her

disposable household income rises, freeing up time and money

to consider sustainability-oriented actions and investments. The

Forts’ sustained liminality results in part from their social

network structure: as a family unit they are tightly connected

through mutual activities and communication while at the same

time having access to a variety of social networks and lifestyles.

The Forts’ maintain a tight central family that facilitates

sustained experimentation with ideas from these diverse

reference points. In this sense, liminality may be sustained as

a core motivation for some individuals, similar to Schwartz’s

(1994) motivations of self-direction and stimulation which both

Table 5

Sub-components of conditions for sustainability-oriented value change.

Conditions for change

Examples observed in this study

1) Lifestyle liminality

2) Alignment with

core values

Sustainability as helping family and friends

(benevolence)

Sustainability as saving the world (universalism)

Sustainability as personal development

(self-direction)

3) Social network

support

Observing similar practices, e.g., HEV ownership

Interpersonal support from influential social

groups

Demonstrated support from strangers

Absence of ridicule from non-sustainabilityoriented social groups

Transition in life, e.g., divorce, new child

Sustained life stage, e.g., retirement

Diverse social network, variety of social groups

Access to resources, e.g., income and time

Lack of routine in daily behavior

score highly on the dimension of openness to change. Although

liminality facilitates the consideration of sustainability-oriented

values, it is not required once sustainability-oriented values are

established. For example, the Rhodes and McAdams have

solidified their self-concepts and behaviors around sustainabilityoriented values.

Second, households need to be able to align the ideas of

sustainability-oriented values and behaviors with their existing

core values. Relating back to Schwartz’s (1994) ten motivations,

households’ framing of motives for sustainable behavior varies

widely, including the potential for benefits to family and friends

(benevolence), the world (universalism), or personal development (self-direction). Several households demonstrated no

interest or sophistication in understanding of sustainability to

start with. Those that were interested in such values faced a

conflict in some cases. The Rancheros decided to emphasize

motivations for their baby daughter’s short term security (due to

safety fears of recharging at home) rather than longer term

benevolence in the sense of preserving her future environment.

Bill Woods’ conformity to others’ self-enhancement based

values (financial savings) quashed his temporary interest in

reducing his environmental impact. In contrast, Ethel Potter and

the Forts discovered that sustainability-oriented values could

align quite well with their core values of self-direction and

benevolence, respectively, without conflicting with other core

values.

Third is a perception of support for sustainability within the

social network. Among the four sustainability ‘‘explorer’’ households, the presence or absence of such support is associated with

their final acceptance or rejection of sustainability-oriented values.

The two households that eventually rejected sustainabilityoriented values described a lack of social support (or opposition)

for such a transition: Billy Woods conformed to the selfenhancement financial motivations of an influential group of

coworkers, and Ed Ranchero was disappointed by the lack of

environmental interest among his friends and coworkers. In

contrast, the two households concluding with sustainabilityoriented values perceived social support: Ethel Potter described

sustainability-oriented interest among her ‘‘favorite’’ daughters

and a new friend, while the Forts were pleasantly surprised to see

hybrid owners welcome them to ‘‘the family.’’

Within the context of this study, each of these conditions

appears to be necessary but not sufficient to facilitate a transition

to sustainability-oriented values and behaviors. Of course, it is

difficult to infer causality from a limited number of observations

and narratives. We thus consider our exploratory findings to be

J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani / Global Environmental Change 23 (2013) 70–80

insights that can inform future research with additional samples in

different regions and contexts of sustainability-oriented behavior.

We further acknowledge that the present focus on a highly

conspicuous, high-identity, environmental symbol (a plug-in

hybrid vehicle version of a Toyota Prius) may not be indicative

of consumer experience with less overt, less-visible pro-environmental technologies, such as programmable thermostats, home

insulation, or energy efficient appliances.

Future research should explore specific processes and subcomponents of each condition identified here. Research could

assess whether the likeliness and strength of liminality effects

differ by types of liminal self-concept, e.g., transitional versus

sustained, financial, temporal, or social contexts, and across

sustainability-oriented behaviors. Further effort could explore

how consumers think about and frame sustainability-oriented

values according to different motivations, e.g., benevolence,

universalism, self-direction, and perhaps others. Potentially,

some people may cast other new or existing values into

a sustainability-orientation under conditions that differ from

the present research. Other studies could also assess what

types of social support are most important in different networks

and possibly for different sustainability practices, e.g., from

closer friends and family, from coworkers, or from technical

experts.

Our exploratory findings do support the notion that widespread

sustainability-oriented values and behaviors can develop over

time, subject to particular conditions. Policymakers seeking to

achieve ambitious sustainability goals, such as achieving deep

reductions in CO2 emissions, will want to better understand and

utilize these levers and dynamics to attain support (or lack of

resistance) to sustainability-oriented policy, and to facilitate the

widespread adoption of sustainable behaviors and technologies

across a variety of contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the California Air Resources

Board, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of

Canada, and the 18 individuals that took part in this study.

References

Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes 50, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., Fishbein, M., 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Atkinson, P., Hammersley, M., 1994. Ethnography and participant observation. In:

Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y. (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Axsen, J., 2010. Interpersonal Influence within Car Buyers’ Social Networks: Observing Consumer Assessment of Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) and

the Spread of Pro-Societal Values. Institute of Transportation Studies, University

of California, Davis, UCD-ITS-RR-10-15.

Axsen, J., Kurani, K.S., 2009. Early U.S. market for plug-In hybrid electric vehicles:

anticipating consumer recharge potential and design priorities. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2139,

64–72.

Axsen, J., Kurani, K.S., 2011. Interpersonal influence in the early plug-in hybrid

market: observing social interactions with an exploratory multi-method

approach. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 16,

150–159.

Axsen, J., Kurani, K.S., 2012a. Interpersonal influence within car buyers’ social

networks: applying five perspectives to plug-in hybrid vehicle drivers. Environment and Planning A 44, 1057–1065.

Axsen, J., Kurani, K.S., 2012b. Social influence, consumer behavior, and low-carbon

energy transitions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 37.

Axsen, J., Mountain, D.C., Jaccard, M., 2009. Combining stated and revealed choice

research to simulate the neighbor effect: the case of hybrid-electric vehicles.

Resource and Energy Economics 31, 221–238.

Axsen, J., TyreeHageman, J., Lentz, A., 2012. Lifestyle practices and pro-environmental

technology. Ecological Economics 82, 64–74.

Bardi, A., Goodwin, R., 2011. The dual route to value change: individual processes

and cultural moderators. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42, 271–287.

79

Bardi, A., Lee, J., Hofmann-Towfigh, N., Soutar, G., 2009. The structure of intraindividual value change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97, 913–929.

Brewer, M.B., Roccas, S., 2001. Individual values, social identity, and optimal

distinctiveness. In: Sedikides, C., Brewer, M.B. (Eds.), Individual Self, Relational

Self, Collective Self. Taylor & Francis, Anne Arbor, MI, pp. 219–237.

Burke, P.J., 2006. Identity change. Social Psychology Quarterly 69, 81–96.

Burke, P.J., Tully, J., 1977. The measurement of role idenity. Social Forces 55,

881–897.

Burnett, R., 1991. Accounts and narratives. In: Montgomery, B., Duck, S. (Eds.),

Studying Interpersonal Interaction. The Guildford Press, New York, pp.

121–140.

Cialdini, R.B., 2003. Crafting normative messages to protect the environment.

Current Directions in Psychological Science 12, 105–109.

Deaux, K., Martin, D., 2003. Interpersonal networks and social categories: specifying

levels of context in identity processes. Social Psychology Quarterly 66, 101–117.

Dietz, T., Fitzgerald, A., Shwom, R., 2005. Environmental values. Annual Review of

Environment and Resources 30, 335–372.

Evans, D., Abrahamse, W., 2009. Beyond rhetoric: the possibilities of and for

‘sustainable lifestyles’. Environmental Politics 18, 486–502.

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior. AddisonWesley, Reading, MA.

Geertz, C., 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, Inc., New York.

Gergen, K., Gergen, J., 1987. Narratives of relationships. In: Burnett, R., McGhee,

P., Clarke, D. (Eds.), Accounting for Relationships: Explanation, Representation and Knowledge. Methuen, London, pp. 269–288.

Giddens, A., 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern

Age. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

Gill, J., Crosby, L., Taylor, J., 1986. Ecological concern, attitudes, and social norms in

voting behavior. Public Opintion Quarterly 50, 537–554.

Heffner, R.R., Kurani, K.S., Turrentine, T.S., 2007. Symbolism in California’s early

market for hybrid electric vehicles. Transportation Research Part D-Transport

and Environment 12, 396–413.

Hitlin, S., 2003. Values as the core of personal identity: drawing links between two

theories of self. Social Psychology Quarterly 66, 118–137.

Hitlin, S., Piliavin, J., 2004. Values: reviving a dormant concept. Annual Review of

Sociology 30, 359–393.

Hogan, B., Carrasco, J.A., Wellman, B., 2007. Visualizing personal networks: working

with participant-aided sociograms. Field Methods 19, 116–144.

Huijts, N., Molin, E., Steg, L., 2012. Psychological factors influencing sustainable

energy technology acceptance: a review-based comprehensive framework.

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16, 525–531.

Jackson, T., January 2005. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change. Sustainable Development Research Network, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, UK.

Kempton, W., Boster, J.S., Hartley, J.A., 1995. Environmental Values in American

Culture. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

McCracken, G., 1988. The Long Interview. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

Norton, B., Costanza, R., Bishop, R., 1998. The evolution of preferences: why

‘sovereign’ preferences may not lead to sustainable policies and what to do

about it. Ecological Economics 24, 193–211.

Oskamp, S., Harrington, M., Edwards, T., Sherwood, D., Okuda, S., Swanson, D., 1991.

Factors influencing household recycling behavior. Environment and Behavior

23, 494–519.