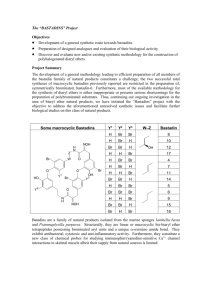

Aziridines and Oxazolines

advertisement