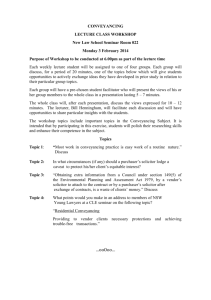

Guide for Solicitors Employed in the Corporate and Public Sectors

advertisement