Theology of Former Prophets 1 Deut Hist

advertisement

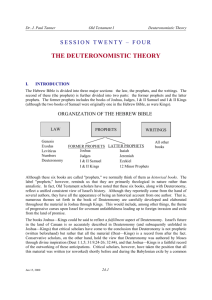

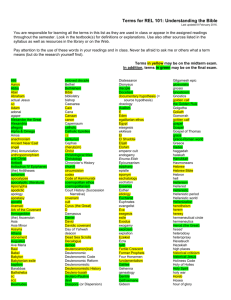

1 The Theology of the Former Prophets (Joshua to 2 Kings) 1. Deuteronomistic History Definition The Deuteronomistic History is the historical work comprised of the books from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings. Origin of the Term In 1670 Spinoza recognized distinctive connections between Deuteronomy and Joshua2 Kings. De Wette saw Joshua as “Deuteronomic” in style and theology and saw Deuteronomy as more closely linked with Joshua than with the Tetrateuch. In the late 19th century critical scholars, recognizing this link, began to speak of the Hexateuch. In 1943 Martin Noth coined the term Deuteronomistic History, proposing that Deuteronomy-2 Kings was a single literary complex. He sees great historical collections in the Hebrew Bible: the Pentateuch, the Deuteronomistic History and the Chronicler’s History. The Rationale Behind the Term Noth argued that Deuteronomy-2 Kings was composed by an editor or writer, the Deuteronomistic Historian (often denoted by the abbreviation Dtr), who drew upon and moulded an extensive collection of older source material to produce a work that had a particular theology and purpose. Noth rejected the hypothesis that each of the books from Joshua to 2 Kings originated as individual units that were brought to their present state by multiple Deuteronomic redactions. He maintained that the history involved in Deuteronomy-2 Kings was so unified and the transitions so smooth that the work as a totality had to be composed by a single editor or author. Why had this editor/author subdivided this history into individual books? Noth believed it was because this editor/author saw this history as made up of five eras: 1. The Review and Reiteration of the Moses era. 2. The Occupation of Canaan under Joshua. 3. The Period of the Judges. 4. The Rise of the Monarchy under Samuel. 5. The Era of the Monarchy. Distinguishing Terms Richter discriminates between terms that concern Deuteronomy and the proposed “Dsource” of the Pentateuch – Deuteronomic and Deuteronomist – and the term used for the historical material influenced by Deuteronomy – Deuteronomistic.1 Approaches to the Deuteronomistic History There are two main lines of approach: 1. Historico-critical exegesis: an approach to the text that seeks to identify sources and redactors. 2. Literary analysis: an approach to the text that views the entirety of the Deuteronomistic History as a literary and theological piece. Usually proponents of this approach regard “the quest for sources and redactors as unproductive Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 2 and even deleterious to true interpretation” and sees virtually the entire Deuteronomistic History as the work of one Deuteronomistic Historian. Deuteronomistic History as History Van Seters has compared the work of the Deuteronomistic Historian to the early Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides, along with many other historiographic writings of the ancient Near East. Distinguishing between modern and ancient history-writing, van Seters sees Israel as a unique civilization within the ancient Near East and, extravagantly, regards the Deuteronomistic Historian as not merely the first Israelite historian but indeed the first historian of Western civilization. I say “extravagantly” because he assumes “history” must be nonpragmatic and nondidactic.2 This not only eliminates much others would view as historical but constitutes a reductionist approach to the Deuteronomistic History itself. Van Seters is opposed to the mainstream historico-exegetical approach to identify sources and layers of redaction: A history is not merely the sum of its parts, and to analyse a history by taking it apart in order to discern the original functions of the various elements will never yield the meaning of the whole.3 Halpern, however, while also emphasizing the form and function of the Deuteronomistic History as ancient history writing marries this with a fresh endorsement of Noth’s basic approach. The Nature and Content of the Deuteronomistic History Joshua-2 Kings, viewed as a whole, begins and ends in a corresponding manner. That is, Joshua is concerned with Israel’s possession of the land of Canaan and 2 Kings ends with first the land of the Northern Kingdom being lost to the Assyrians and then the land of the Southern Kingdom being lost to the Babylonians. Noth pioneered the view that the Deuteronomistic History was written to explain how Israel’s sins led to the catastrophe of exile and saw this as the ideology which gave coherence of thought to the work. Von Rad found Noth’s portrayal of the unifying note of retribution too unbalanced, failing to factor in the historian’s emphasis on the Davidic covenant and along with this the equally powerful messages of hope and grace. Indeed, the historian’s chosen conclusion to the epic work – the release of Jehoiachin from a Babylonian prison (2 Ki 25:27-30) – aims at keeping the Davidic hope alive. Wolff concurred, though seeing this closure not as an explicit hope but allowing for the possibility of hope in repentance, while also noting texts in the Deuteronomistic history which anticipate such a possibility in their concern with Israel’s return and Yahweh’s mercy. These books comprise a theological history, being concerned to explain the development and ultimate failure of Israel as an independent political entity in the land of Canaan as tied up with Israel’s covenant relationship with Yahweh: The history’s overarching agenda is to explain Israel’s covenant relationship with God, and how the failure of this relationship eventually leads to the nation’s demise at the hands of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE (Richter, 220). Cross pointed out that it was Noth’s negative view of the purpose of the Deuteronomistic History that caused him to assume that such positive components as Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 3 Nathan’s prophecy (2 Sam 7:1-7) and David’s speech (2 Sam 7:18-29) were not Deuteronomistic. Clearly Cross is quite right, following McCarthy against Noth, to insist that 2 Samuel 7 be treated not only as a legitimate part of the core materials of the Deuteronomistic History, but, indeed, as essential to it as the transitional speeches of Deuteronomy 31 and Joshua 23. As Cross contended the texts concerning the Davidic covenant emphasise God’s promise of a never-ending kingdom and thereby bring a theme of grace to the Deuteronomistic History. Cross argues that the two great themes of the Deuteronomistic History are: 1. The sin of Jeroboam I and its consequences. 2. The faithfulness of David and its consequences. According to Cross, it is this underlying agenda that explains why the bulls of Bethel and Dan are juxtaposed with the ark and the Jerusalem temple and why the summary speech concerning the removal of Samaria, the Northern Kingdom (2 Ki 17) contrasts with the reform of Josiah (2 Ki 22). Sources for and Redactions of the Deuteronomistic History According to Noth this source material was made up of the following sources: 1. The Deuteronomic Law. Richter (228) strongly supports Noth here.4 2. Joshua 1-12. 3. Two collections of stories, one regarding various tribal heroes, the other regarding “minor” judges. 4. An extensive collection of Saul-David traditions. 5. The historiographic texts cited throughout the books of Kings: a. “The Books of the Chronicles of the Kings of Israel.” b. “The Books of the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah.” c. “The Books of the Acts of Solomon.” Since Noth other scholars have argued that the work of the Deuteronomistic Historian was itself was subjected to further redactions to produce the final form of Deuteronomy-2 Kings. There are two main schools of thought here: 1. The Harvard School hypothesis (initiated by Cross). This proposes a pre- and a postexilic redaction of the Deuteronomistic History. The pre-exilic redaction dates to the days of Josiah and the remainder is adjudged to be an early exilic redaction, updating the main body of the Deuteronomistic History to make it more applicable to an exilic audience. 2. The Göttingen School hypothesis (initiated by Smend Jr.). This proposes three postexilic redactions to the Deuteronomistic History. The Harvard School Cross believed that the first composer of the Deuteronomistic History, Dtr1, had no inkling of the catastrophe that was to befall the Davidic kingdom and so presented Josiah’s reforms as the climax to the initial history. So Dtr1 was designed as a propaganda document for the Josianic reform somewhere between 621 and 609 BCE.5 Favourable to this reading is the disproportionate stress placed on the righteousness of Josiah. Cross next argued that following the exile (c. 550 BCE), another redactor, Dtr2, updated the work and reshaped the history, with minimal reworking, to make it “relevant to exiles for whom the bright expectations of the Josianic era were hopelessly past.”6 In particular, this updated version now attributed the fall of Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 4 Jerusalem to Manasseh’s wickedness which had canceled out the virtues displayed by Josiah in his reforms.7 Cross maintained that Dtr2 was responsible for the subtheme of inevitable rejection interspersed throughout the final form of the Deuteronomistic History. Cross’ demarcation between Dtr1 and Dtr2 presupposes that these redactors had differing assessments of the Davidic covenant: Dtr1 treating it as unconditional and Dtr2 as now conditional. But Nelson and Halpern have rightly pointed out that the preexilic Davidic covenant was itself both conditional and unconditional. The Göttingen School Smend adopts Noth’s Deuteronomistic Historian whom he calls DtrG and later DtrH. DtrH is responsible for the core history which was compiled in the early exilic period. But later on, DtrN (the “N” stands for “nomistic”), being more law-oriented, edited the work to introduce two themes important to him, namely the law and foreign peoples remaining in the land.8 According to Smend, DtrN believed “obedience to the law was crucial to the successful conquest of the land, and… the ongoing presence of foreign peoples within the land demonstrated that the law had not been observed”.9 Later Smend speculated that DtrN may also have been responsible for the insertion of Deuteronomy 4-30 into the Deuteronomistic History. Smend’s student Dietrich, believing DtrN was the last of three redactors, proposed that a second redactor, DtrP (the “P” stands for “prophecy”) augmented the core history with a significant number of prophetic narratives and oracles. Dietrich maintained that the prophecy/fulfillment schema within the Deuteronomistic History was due to DtrP’s hand.10 But the argumentation here is highly dubious especially given that the theology, language and ideology of the supposed DtrH and DtrP contributions are extremely similar. Serving to reinforce the Göttingen School hypothesis Smend’s student Veijola understands the differences between the three redactors as follows: 1. DtrH: pro-David and promonarchy. 2. DtrP: generally antimonarchy. 3. DtrN: pro-David but generally anti-monarchy. McConville (84) dismisses Veijola’s theory as fanciful, and illustrative of an approach that “produces improbabilities at the level of detailed interpretation” and involving a “tendency to produce false distinctions”. He finds both Cross and Smend to have “an inadequate understanding of the subtle ironies of the literature” so that “ideas that seem to be in tension with each other are parcelled out to different propagandists” (84-85). The notion that numerous redactions were involved in producing the Deuteronomistic History has also been argued by scholars such as Weinfeld and Nicholson who speak of a “school” or “circle” of Deuteronomists responsible for such editorial work during the period from Hezekiah to the early exile. They take the view that this Deuteronomistic school was committed to propaganda, promoting the centralization of the cult in Jerusalem. Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 5 Depending on what view of redaction is taken then there will be accompanying hypotheses concerning the place or places of composition. Most still prefer Palestine as the main place of composition, though Nicholson and Soggin argue for Babylonia (Klein, xxix). Of course, all arguments that involve identifying different redactions necessarily must seek their justification in an appeal to textual features. So, for example, Halpern and Vanderhooft make much of the so-called “skeletal formulary” around which the books of Kings have been constructed, namely formulae involving the evaluation of the king, his death and burial, the naming of the queen mother, and so on. They see this as indicating that a shift in the authorship of the Deuteronomistic History took place during Hezekiah’s reign – a Hezekian redaction (first proposed by Weippert). Person comments on the fundamental problem that faces all who seek to discriminate different redactions: The problem lies in the inability of redaction criticism to distinguish one Deuteronomic redactor from another Deuteronomic redactor, since all Deuteronomic redactors use similar Deuteronomic language and themes!11 There has been a growing tendency in recent times, as illustrated by Westermann and McConville12, to treat the Deuteronomistic History as a somewhat loosely edited corpus and to emphasise the distinct books within this corpus as independent works. Since the entire attempt to identify redactions is highly speculative there is seemingly no end to the speculative theories advanced concerning redactional processes. Some recent examples include13: 1. Minimalists: Van Seters contends there were no earlier sources prior to the Deuteronomist and that he invented all his materials.14 2. Knauf: the independent books within the so-called Deuteronomistic History are themselves the result of “fundamentally unrelated exilic and postexilic redactions” (Knoppers). 3. Auld: a Q-type source was shared by both Kings and Chronicles and this influenced the theology of Deuteronomy, not vice versa. 4. The “block model”: larger segments of the so-called Deuteronomistic History, incorporating separately authored books, were redacted late in the editorial process. 5. There is no such thing as a Deuteronomistic History and no editorial coherence to the work. 6. The “pan-Deuteronomic” trend: “the concept of Deuteronomism has become so amorphous that it no longer has any analytical precision and ought to be abandoned” (R. Wilson). Richter (227) concludes that Deuteronomistic studies are currently characterized by confusion and he attributes this to an overly optimistic opinion of who much redactional activity might be isolated within a finished piece, augmented by the atomistic tendencies that seem to be inherent to the critical methodologies of OT exegesis. This is coupled with a lack of respect for the ancient historian, assuming he “would be incapable of maintaining a complex perspective on the subject matter, or unable to hold conflicting views in tension” (Richter, 227-228). Similarly, McConville observes in Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 6 responding to Smend: “the explanation of the theological poles of the discourse as rival points of view enshrined in successive redactions precludes the recognition of theological profundity” (83). As noted above, the books of Kings explicitly record the use of sources. In principle there can be no objection to the idea that sources were used in the composition of the Deuteronomistic History (cf. Luke 1:1-4), though some like van Seters, have adopted a minimalist view. However, even if we acknowledge the use of such sources it remains a matter of debate whether it is possible to identify retrospectively any of those sources and, if it is possible, whether it is possible to discriminate clearly between them. Such uncertainties have not deterred critical scholars. Take the matter of discriminating between pre-exilic and postexilic material. For example, McConville argues that the stories of Elijah and Elisha (1 Ki 17-2 Ki 9) “do not fit immediately into an exilic purpose to explain theologically the fall of Jerusalem” (68). He believes they fit best with a Sitz im Leben in a period “when prophecy was young in Israel and when the pressing issue was the survival of Yahwish in the face of strong competition from the religion of Baal”. But this attempt to identify this material as pre-exilic relies on questionable and highly subjective assumptions. Do we not also see in the Elijah-Elisha narratives the outworking of the truth that there is “an Israel within Israel”; that God keeps a remnant for himself even with the nation as a whole is apostate? To the extent this is so does this not in fact fit very well with an exilic perspective, sounding a note of hope for the future? Further, even if we can agree that particular textual material is pre-exilic does this necessarily mean that it involves a pre-exilic perspective? The highly subjective nature of assumptions underlying identification of different sources is well illustrated by one of Cross’ major reasons for discriminating between two editions of the Deuteronomistic History. That is, because of his blindness to the use of irony in 2 Kings 23:25-27 Cross drew the conclusion that verse 25, which hails Josiah as the greatest of the Davidic kings, is incompatible with verses 26-27, which justifies God’s removal of Judah and rejection of Jerusalem and the temple as due to the sins of Josiah’s predecessor, Manasseh.15 As Hoffmann has shown, the Manasseh account is of major importance, forming a link backwards with an allusion to Ahab (2 Ki 21:3) and forwards to Josiah, for whom Hezekiah has already served as a prototype, including the ominous visit of the Babylonian emissaries (2 Ki 20). There is throughout the work an “increasing momentum of the ‘pendulum-swings’ from” positive to negative cult reform, signaling that the finale is near, so as to demonstrate that “the ‘success’ of Josiah is part of a story that is ultimately one of failure”.16 Another illustration of the subjectivity involved in source-identification is provided by Provan’s dubious analysis of the treatment of “high places” in the Deuteronomistic History. This leads him to discriminate between texts before Hezekiah, which he thinks are concerned only with the need for centralization, and texts after Hezekiah in which hostility to idolatry is prominent. As McConville (81-82) observes, Provan’s interpretation of individual texts is open to challenge and his attempt to drive a wedge between Hezekiah and Josiah is unconvincing. The Unity of the Deuteronomistic History Noth identified the following features as pointing to Joshua-2 Kings as a unified work: Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 7 1. The repetition of similar phraseology. 2. The prophecy/fulfillment schema of the history. 3. The strategic appearance and function of unifying speeches and narratives by the leading characters. 4. The integrated and stylized chronology. 5. The overarching Deuteronomic ideology. 6. The singularity of thesis is “the great unifying factor in the course of events”, namely the historian’s perception of “a just divine retribution in the history of the people”: The meaning which he discovered was that God was recognizably at work in this history, continuously meeting the accelerating moral decline with warnings and punishments and, finally, when these proved fruitless, with total annihilation (Noth, cited by Richter, 222). The unity of the Deuteronomistic History is also obviously indicated by the way Joshua2 Kings reads as a connected story. The Continuing Storyline McConville sees this expressed “at the ‘joints’ between the books” (73): 1. Deuteronomy prepares for the post-Mosaic era by introducing Joshua as the new leader (Deut 31:1-8; 34) and this is recalled at the very commencement of the book of Joshua (1:1-9), including reference to the foundational importance for Joshua of the “Book of the Law”, presumably Deuteronomy (Josh 1:8). Compare also Joshua 8:30-35 with the ceremonies commanded in Deuteronomy 27. Deuteronomy promises and commands Israel to possess the land and Joshua relates how this was realized. 2. Judges opens with an allusion to the death of Joshua and develops further the story of the conquest. The refrain “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as he saw fit” prepares for the story of the origin of kingship in 1 Samuel. 3. David’s lament for Saul and Jonathan at the beginning of 2 Samuel (1:7-27) forges close links with 1 Samuel and 2 Samuel advances the theme of kingship still further, especially with the Davidic covenant of 2 Samuel 7. 4. The book of 1 Kings flows naturally on, culminating the story of David and his sons, with now Solomon placed securely on the throne. 5. The Babylonian exile is anticipated in 1 & 2 Kings (Hoffmann & Hobbs).17 Other Points of Connection Illustrating the Unity of the Work18 This includes the following: 1. The promise-fulfillment schema: a. Deuteronomy’s promise of land fulfilled in Joshua. b. The promise of “rest from enemies” associated with finding the place Yahweh would choose for his worship (Deut 12:5-11) and fulfilled when David completely subdued the land (2 Sam 7:1), when Jerusalem was established as the proper place of worship due to the ark being located there (2 Sam 6) and when Solomon was free to build the temple because of the prosperity and peace granted to him (2 Ki 5-8). 2. Joshua’s covenant with the Gibeonites (Josh 9) is recalled in 2 Samuel 21:1-6, an implicit violation of Deuteronomy 7:2. 3. The covenantal language of the major speeches, identifiably Deuteronomic. 4. Various theological ideas: Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 8 a. Israel’s possession of the land and the conditions on which this can be realized and maintained. i. In Judges “the land is held intermittently and in varying degrees according to the faithfulness of Israel to Yahweh” (McConville, 76). ii. In 2 Kings the land is lost due to idolatry, the most heinous sin (Deut 7:1-5; 13; cf. 1 Ki 11:1-10). b. Leadership. i. The understanding of God as Israel’s king (Deut 33:5) requires that any human king in Israel be subject to God’s law and act as a “brother” (Deut 17:14-20). ii. In Judges Gideon refuses to accept the title of king (Judg 8:2223). iii. The demand for a king in 2 Samuel 8 is met with Samuel’s anger, with warnings about the danger of the kind of royal tyranny spoken against in Deuteronomy. c. Covenant. Kingship becomes incorporated into the covenantal theology of Israel, with 1 Kings 2:2-4 making it clear that the David covenant (2 Samuel 7) is to be understood along Deuteronomic lines. The Deuteronomic History and the Influence of Deuteronomy Noth identified the Deuteronomic Law as the “first large-scale complex of tradition” employed by the Deuteronomistic Historian, namely Deuteronomy 4:44-30:20 (minus additions) and Deuteronomy 1-3, with possibly some parts of Deuteronomy 4. He also saw Deuteronomy 31-34 as an original composition used by the historian to enable the transition to Joshua. Noth believed that it was the theology of Deuteronomy that dictated the historian’s entire treatment of Israel’s history. Noth saw key speeches, at important historical junctions in the Deuteronomistic History, as following the pattern set by Moses’ opening speech in Deuteronomy19: 1. Joshua’s monologues (Josh1:11-15; 23:2-30) initiating and concluding the era of the settlement. 2. Samuel’s speech (1 Sam 12:1-24) effecting the movement from the era of the judges to the monarchy. 3. Solomon’s prayer (1 Ki 8:12-51) summarizing the era of the united monarchy, introducing the temple era and foreshadowing the divided monarchy. Cross made much of the absence of Nathan’s oracle (2 Sam 7:1-17) and David’s speech (2 Sam 7:18-29). Noth attributed these particular speeches to sources other than the Deuteronomistic Historian. For example, he found it inconceivable to think of Nathan’s speech as Deuteronomistic because of the way it prohibited temple-building and stressed so strongly the value of the monarchy. Noth saw the three speeches he had singled out as all concerned with looking forward and backward in an effort to interpret the course of events and to draw relevant practical conclusions about what the people should do. He saw instances of the narrator’s own reflections as accomplishing the same purpose: 1. The summary of the conquest battles (Josh 12). Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 9 2. The discussion of Israel’s sin and its consequences in the era of the judges (Judg 2:11-23). 3. The explanation of the Northern Kingdom’s demise (2 Ki 17:7-18, 20-23). Noth found this historian’s use of such retrospective and anticipatory insertions as unparalleled in the ancient Near East. Later van Seters has found this exact method also used by Herodotus and Thucydides. Richter (226-227) challenges the view that the Deuteronomistic History involves a “near-material presence of the deity”, which serves as the “deuteronomistic correction” to the perspective of the JE source(s), namely of “the anthropomorphic and immanent presence of the deity”. The so-called “Name Theology” that underlies this contested approach posits a three-stage immanence to transcendence evolution concerning the mode of divine presence at the cult site: (1) the JE immanence perspective; (2) the near-material perspective of the Deuteronomistic History; and (3) “the abstract, demythologized, and transcendent presence in the P source”. Richter demonstrates that at the heart of such Name Theology lies a fundamental misreading of the key Deuteronomic phrase lĕšakkēn šĕmô šām which is synonymous with the following expression in the Deuteronomistic History: lāśûm šĕmô šām (1 Ki 9:3; 11:36; 14:21: 2 Ki 21:4, 7). The Deuteronomic phrase is usually rendered “[the place where Yahweh] will cause his name to dwell”. But Richter has demonstrated that this phrase is a loan-adaptation of a cognate Akkadian phrase Akk šuma šakānu, which means to place one’s inscription on a monument or to install an inscribed monument. Consequently, lĕšakkēn šĕmô šām should actually be rendered “[the place where Yahweh] will place his name”, with Yahweh’s “name” being here associated with an inscribed monument, not a semi-hypostatic presence. 1 S.L. Richter, “Deuteronomistic History” in Dictionary of Old Testament Historical Books (eds. Bill T. Arnold & H.G.M. Williamson; Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press; Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press, 2005) 220. 2 Yamauchi observes that van Seters bases much on his definition of history taken from Huizinga: “History is the intellectual form in which a civilization renders account to itself of its past.” As Yamauchi notes, van Seters applies this definition in an arbitrary and narrow way to designate national history, with the assumptions I’ve noted in the main body of the text. See Edwin Yamauchi, “The Current State of Old Testament Historiography” in Faith, Tradition, and History. Old Testament Historiography in Its Near Eastern Context (eds. A.R. Millard, James K. Hoffmeier & David W. Baker; Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1994) 2. 3 Cited by Richter, 226. 4 However, he questionably follows Mendenhall in seeing the literary form of the book of Deuteronomy as reflective of ancient vassal treaties. 5 See Klein, xxix. 6 Cited by Richter, 223. 7 See Klein, xxix. Klein dissents, seeing the critique of Manasseh as not “different in kind from the historian’s use of Jeroboam as a whipping boy in the North.” Klein refers to his Israel in Exile in which he “argued that Rehoboam and Manasseh were singled out for theological critique in the South just as Jeroboam and Ahab were for the North.” 8 Veijola identified DtrN in 1 Samuel 7:2ab; 3-4; 8:6-22a; 10:18abg-19a; 12:1-25; and 13:13-14. 9 As summarized by Richter, 224. 10 Veijola identified DtrP in 1 Samuel 3:11-14; 15:1-35; and 28:17-19a. Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008 10 11 Cited by Richter, 227. However, McConville recognizes that the original fragments from which Joshua-2 Kings was presumably composed “cannot easily be equated with the books into which the material has been divided since ancient times, for while Joshua and 1, 2 Samuel relate to relatively short periods, Judges and 1, 2 Kingsclearly do not”. See J. Gordon McConville, Grace in the End. A Study in Deuteronomic Theology (Studies in Old Testament Biblical Theology; eds. Willem VanGemeren & Tremper Longman III; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1998) 67. 13 Most of these are presented by Richter, 227. 14 See Yamauchi, 5. 15 See McConville, 80. 16 McConville, 86-87. 17 McConville, 85. 18 See especially McConville, 74ff. 19 Richter (228) sees transitional speeches as a major literary device serving to structure the Deuteronomistic History. 12 Michael K. Wilson www.facetofaceintercultural.com.au July 2008