Municipal Government in Vietnam

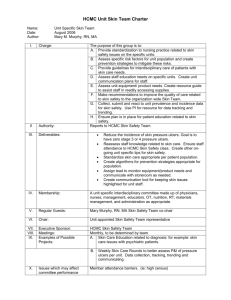

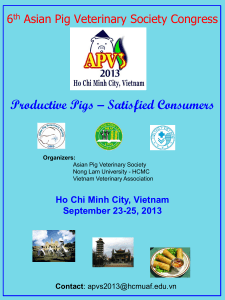

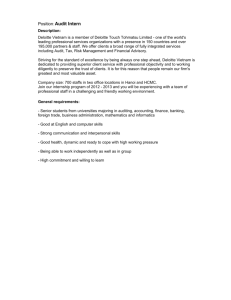

advertisement