MARKETINGMMGEMm - American Marketing Association

advertisement

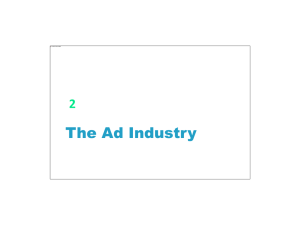

MARKETINGMMGEMm 30 U2J0.2 IMRKETING mMMNl byjakkij. Mohr and George S. Low Escaping the Catch-22 of Trade Promotion Spending It takes discipline and courage, but some packaged-goods marketers are breaking a bad habit. C onsumer-goods manufacturers are caught in a catch-22 situation: They want lo break the costly cycle of trade promotion spending, but find themselves either unwilling or unable lo wealher the resistance from retailers and their own sales managers. For at lea.st 10 years, executives have been questioning whether the benefits gained from trade promotions are worth the increasing costs. The proportion of marketing communication.s budgets allocated to trade promotion was 44.9% in 1992, according to Donnelley Marketing's 15th Annual Survey of Promotional Practices. Trade promotions can help a firm acquire not only short-term sales increases, but also crucial shelf-space and other advantages in merchandising and point-of-purchase activities. But lowmargin sales don't generate incremental profits, and many marketers arc watching sales erode because of trade promotion activity. Their trade promotions expenditures usually shortchange brand- and consumer-franchise building activities such as advertising. The managers we interviewed said that many problems result from heavy reliance on trade promotion, including lower sales in the product category and less favorable consumer percep- tions of product quality, among others (see box on page 33). As two respondents said: • "There comes a poinl of diminishing returns, where you keep throwing dollars at a customer. EXECUTIVE BRIEFING C onsume!--goods manufacturers want to cut their bloated trade promotion budgets, but demanding retailers, volume-hungry sales managers, and shortterm corporate financial targets stand in the way. Some marketers say they are breaking free, however, with tough-minded strategies focused on long-term brand profitability. The authors' research among packaged-goods manufacturers finds them using a variety of techniques to build brand value, customer loyalty, and ttade partnerships. They are proving that even though the trade promotion addiction is formidable, it is not insurmountable. MARKETING MANAGEMENJ and you get fewer and fewer cases in return proportionately." • "You know, it would be one thing if [spending on trade promotions | were working and we were just worried about the long-term impaet on the brand...but it's not even working." Managers face a variety of pressures to increase trade spending. In addition to demands from retailers, eompetition from privale-label and other manufacturers, and less brand-loyal consumers, marketing managers must deal with pressures from within their own firms to meet short-term financial and unit volume targets (see Exhibit I). For example, sales managers lobby for increased trade promotion budgets because they are rewarded for short-term sales, and the reward systems for brand managers encourage near-term volume and profit hits. The managers we interviewed say pressure from within the firm to drive market share with promotions may be greater than the demands of the market. They find it very difficult to withdraw from their addiction to trade promotions. Firms that do attempt to curtail trade spending will experience some pain. According to widespread press reports. Safeway recently retaliated against Procter and Gamble's efforts to cut back on trade discounts by dropping some less-popular P&G sizes and brands. And marketers will have to accept the negative impact such a move will have on revenue—namely decreases or smaller increases in volume and market share. But firms that don't make the attempt will likely experience even more pain in EXHIBIT Pressures on brand managers to increase trade promotion spending Organizational factors greater competition retailer's power media fragmentation more private iabels decreasing bran(J loyalty 32 M2J0.2 Macro environment! L slow population growth economic recession short-term focus reward system pressure from sales force the long run when they see their profitability eroding further. Managing Budgets M anui^ing trade promotion spending, rather than allowing budgets lo mushroom out of control, will set marketers on ihe road back to sanily. It's not so much a question of which firms will bring their trade budgets under control, but rather which ones will do so in a proactive manner. The managers in our study offered novel solutions to some of the common problems. PROBLEM: Adversarial retail relationships. SOLUTIONS: • Establish partnerships/alliances with the trade. • Be creative in promotion planning. • Work on communicating better. • Initiate team selling. • Try an every-day low purchase price strategy. Retailers use their power to convince manufacturers to give them more and deeper discounts, better dating, better case rates, higher slotting allowances, and other concessions for distribution coverage and support. Their demands for payment are more exacting when manufacturers want shelf space for new products. If manufacturers don't pay. many retailers simply refuse to continue carrying the product. Threatening manufacturers with loss of distribution can be very effective—particularly when retailers can pit one competitor against another or emphasize private labels. Brand managers, therefore, often build their budgets on the premise that trade dealing is part ofthe cost of doing business. As one brand manager we interviewed said, "There's a certain cost of doing business that the trade demands just to keep your slots. To keep your distribution, you have to run a certain number of trade promotions." Companies have allocated larger and larger amounts to trade promotions and, in doing so, have seen retailers forward-buy, stockpile, divert purchases from areas where discounts are greater, and postpone purchases until deals are available. Escaping the Catch'22 of Trade Promotion Spending Consumers also are affected by increases in trade spending. They have learned to either stockpile or postpone purchases on the basis of dealing activity at the point of purchase. Because of the increased swings in purchase behaviors, stockouts have become more common. And the increasing costs of implementing promotions are being passed along to consumers in the form of higher shelf prices. At the same time, retailers face their own competitive pressures to have promotable prices and low-price images in competitive markets. Some manufacturers recognize this dilemma and are forming closer relationships with trade members. Soliciting retailers' input can create winwin solutions in spending marketing dollars. For example, one manager said his firm was trying to form partnerships by engaging in category management and working more closely with retailers to achieve long-term growth. This manager had succeeded in showing retailers that market segmentation and strong advertising increased sales for the product category in the long term. He complained that "slotting allowances get in the way of thai. Just because a retailer says. 'Hey. I have another principal that is giving me a deal, and unless you do that too, you're not going to get in,' doesn't mean the firm should cave in. That's real short-term thinking." Manufacturers also can differentiate themselves and encourage retailer loyalty through alliances or electronic data interchange (EDI) links with the trade, such as Wal-Mart's celebrated state-of-the-art EDI system. Offering unique advantages to a business partner is a more solid position than simply offering large discounts. Engaging retailers in creative promotion planning will meet both parties" needs. Manufacturers and retailers will get more value out of trade promotion dollars by using techniques such as direct product profitability, compensating retailers for long-term growth, cooperative advertising, and joint promotions. One manager we interviewed told of using joint promotions in which the retailer places high-value coupons in its ads and the manufacturer redeems them just as if they were manufacturer's coupons. He said that the ability to target the promotion was the key advantage; the price point was not that important. And he found he didn't have to trade-deal when he participated in this kind of in-ad program. Manufacturers also are finding that better communication with trade members can make a big difference. By engaging in effective dialogue, manufacturers and retailers can better understand each other's needs and goals. One manager in our study thought that much of the problem in retail relationships was due to the tact that retailers don't understand the constraints of the manufacturing environment, and vice versa. She said firms could build teams to identify problems and come up with solutions. Forming teams to call on retail customers also gives manufacturers an opportunity to cement trade relationships. For example, one manager said: "We started this year with the concept we call team selling. The person responsible for calling on the customer, together with people from our distribution department, our credit department, logistics, and marketing, form a team to go in and work with our customers, addressing all areas of the business. We see how we can do things better to satisfy the customer and, obviously, to satisfy ourselves." Finally, if retailers adopt an every-day-Iowprice policy, the haggling over trade promotion deals will end. Replacing trade promotions— which can cause wild swings in sales and prices—with relatively stable, low prices would ease time and cost pressures of implementing price promotions and reduce the mistrust that exists between manufacturers and retailers and between business and consumers. And it potentially could result in higher profits. The Study T he authors interviewed 21 managers at eight consumer-products finns as part of a larger research project, funded by the Marketing Science Institute, on how these firms allocate monies to advertising and/or sales promotion. The respondents included brand/product, sales, market research, promotion, trade, and category managers who were guaranteed anonymity. In personal interviews of approximately 45 minutes in length, the authors asked these managers about their companies' budget allocation process, the factors that influence the process, and their evaluation of how effective the allocations are. All interviews were taped, transcribed, and analyzed for key themes that emerged across interviews. This article incorporates the insights of these managers in formulating workable solutions to the problems manufacturers face when trying to curtail trade promotion spending. mRKETING mmOEMENJ 2ZZ Trade promotion spending competitive retaliation. SOLUTIONS: • Focus on advantages to the retailer. • Help retailers sell more of the category. • Convince consumers to buy more product at full price. Relying on trade promotion leads brands to a viciou.s cycle in which competitors match each others' trade allowances, pushing them beyond reasonable levels. Powerful retailers demand that the promotional discounts und slotting allowances continue, threatening manufacturers that do not comply with potential loss of distribution. The managers in our study said that getting out of this bind is difficult, but not impossible. To get retailers to accept smaller trade allowances, even as competitors continue to deal, managers have to focus on advantages to the retailer. One vyay to do this is to help retailers sell more ol' the category. All other things being equal, retailers don't care which manufacturer's brand they sell; what they want to do is increase total sales in the product category. Manufacturers can help retailers accomplish this by balancing consumer advertising and price Incentives. One firm recently decided to take a leadership position in its category by returning to network TV. "We'll grow stronger because we'll bring more people in and increase purchase frequency and use. So it's a win-win situation," said a company brand manager. The trade reaction to the plan was mixed, however. Half of the retailers bought it, accepting lower trade budgets in exchange for stronger advertising: but the other half said. "Well, that's great, but Where's my money?" The firm held its position, refusing to restore allowances to retailers who balked. The manufacturer felt a longer-term outlook ultimately would be better for all the parties involved. In fact, this manufacturer felt more advertising by competitors would help the situation: "Our competitors still haven't figured it out—they keep hammering away at the trade side, hoping that will drive the business...," said the brand manager. "However, when ali three brands advertise, the category does respond." Another way to keep retailers happy is to sell more product at full price, rather than at discounts. becau.se retail margins will be higher. The question then becomes, how do manufacturers (and retailers) get consumers to buy more product at the regular price? Managers in our study indicated that a strong 34 2. No. 2 product position is crucial to convincing consumers to buy products at full price. PROBLEM: Trade dollars steal funds from advertising. SOLUTION: ' Create a powerful position to justify ad spending. Exhibit 2 shows the relative proportion of funds spent on advertising, consumer promotions, and trade promotions over the last 10 years. In 1981, the Donnelley survey found media advertising accounted for 43% of marketing communication budgets, while trade promotions accounted for 34%; by 1992, those figures were reversed, with media advertising accounting for 26.9% and trade promotions 44.9% of marketing communications budgets. A contributing factor to the decline in ad spending is managers' need to make annual profit and volume goals: when such goals arc not being reached, advertising is an easy target at which to aim cuts. Part of the decline is due to the ease with which managers can slice ad budgets to meet profit goals. They are less likely to cut trade promotioEi. which has a more immediate and visible effect on volume. One firm's solution is to focus on the power of the brand with a clear, consistent, and salient positioning strategy—some point of meaningful differentiation that advertising can comrnunicate. justifying a larger advertising budget. As one brand manager noted. "Let's say you had news on a brand. A new type of packaging or something of breakthrough value, like a new fiavor or fat free. That news is always a great reason to advertise. So if you're finally able to bring some news to the category to maximize the value of being first with a product innovation or improvement, you would definitely tend to advertise that." If the message is powerful, consumers will be willing to pay more to acquire a brand, and demand, rather than trade allowances, will ensure the brand's distribution. Also, as we will point out. advertising has a stronger positive effect on brand profit than trade promotion. Heinz is one manufacturer that has been following this strategy. According to press reports, the company's CEO has granted increases in advertising budgets to build brands. PROBLEM: Devalued brand image/los.s of consumer brand franchise. SOLUTIONS: Rc-turgct consumer groups. Use integrated marketing communications. Escaping the Catch-22 of Trade Promotion Spending Ad budget erosion has negative implications for brand image and consumer franchise. As one manager said. "'You can put a lot more money into trade promotion than your competitors, but if they heavily outspend you in advertising, you still get killed on the shelf. It comes back to equily—you have to have better brand equity." In addition, a high product-quality positioning is incompatible with a lowprice strategy. Managers can build brand equity by focusing on the power of the brand, but they also need to segment consumer markets according to buying behavior. One company carefully evaluated its customer segments on the basis of customer loyalty and frequency-of-purchase/consistency-of-usageover time. In segmenting the market based on these variables, the firm found four discrete groups of customers, two of which the manager detailed for us. The top group—the "'enthusiasts"—consisted ofa small percentage of households that accounted for a reasonable piece of the volume and had the highest profitability. At the bottom of the pyramid was the "price-sensitive" group, a large percentage of households accounting for the largest percentage of volume, but with a commodity orientation. These consumers were one-tenth as profitable as the enthusiasts because they bought more than 50% of the product on deal. Interestingly, the difference in the average price paid between the enthusiast and the price-sensitive consumer was only 13%. But the finn was using 20%, 25%, or 30% deals, when it needed only 13% deals to get these switchers to buy their product. The implication of this firm's segmentation strategy was that the most loyal, most consistent, and most frequent consumers didn't need a price reduction to buy: they needed reminder triggers in the advertising to stimulate purchase. This helped the fuTTi wean itself from price deals. "The marketing plan we presented yesterday, one that we're very proud of, [includedl price pro- EXHIBIT 2 Share of promotional expenditures by packaged goods firms 50- 3 40- 30- Consumer Promotion 20 - 1 I I I I I 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 YEAR Source: Donnelley Marketing's Armual Surveys ot Promotional Practices. UARKHING mNAGEmi 2Z5 motions at only 7% and lower deal frequeticy," said one of the company's managers. "The competition is out there at 20%-25% and higher frequency. We've taken tremendous hunks of the [trade] budget out, some of which we dropped to the bottom line, others which we've invested back into advertising." By refocusing some of the savings to advertising, the company enhanced its brand image, built its consumer franchise, reinforced consumer loyalty, and maintained overall profit. A segmentation strategy has inevitable implications for promotional practices. A firm cannot be everything to everyone. To succeed in segments it can dominate, a company must make a tradeoff among disparate segments, choosing, for instance, either price-sensitive buyers or price-insensitive brand loyalists, but not both. Many firms are finding that promotions are less likely to devalue brand image if they are part of an integrated marketing communications campaign. For example, trade dollars can be used to stimulate cooperative advertising, or consumer promotions can be tied to advertising themes. Ties between promotions and advertising dollars add synergy to the campaign. One firm reallocated trade dollars from price reductions to merchandising activities such as end-aisle displays, features, and in-store programs that contributed to building brand image and moving more retail volume. " Improve evaluation by computing elasticities. structure of business today doesn't allow for someone to plead the case for powerful advertising ideas. And product managers are not good at it, and agencies are sometimes their own worst enemy. They need to adapt—they need to downplay the brilliance and creativity and make it seem safe, logical, rational...." Brand managers also are not well-trained in advertising issues. According to the same manager: "Brand managers don't understand advertising because they lack the aptitude—advertising is an art form. They can't think conceptually. It's hard to learn, and universities aren't terrific in teaching advertising." Marketers can justify increases in advertising spending in two ways. First, they should measure advertising and promotion elasticities: How much a change in advertising or promotion spending affects sales (i.e., the percentage of change in sales divided by the percentage of change in advertising expenditures). John Philip Jones of Syracuse University suggested this technique in a 1990 Harvard Business Review article, for example. In addition, firms should work on improving managers' understanding of advertising. Agencies can help in this endeavor by changing the way they present advertising to the client. By focusing on advertising testing and research, the case for increased advertising budgets will be more convincing. Changes in MBA programs also would be helpful because future managers need to understand what makes an ad campaign effective. Marketing students today know budgeting techniques, media planning, and other business management aspects of advertising, but are less informed about creativity, emotion, and behavioral science. • Educate managers about advertising. PROBLEM: PROBLEM: Lack of solid measures of advertising effectiveness. SOLUTIONS: Managers said increases in trade promotion dollars are due, in part, to the fact that it is so difficult to measure returns from advertising expenditures. The response from trade promotion is more predictable than the elusive long-range results of a new ad campaign. Because managers are facing pressure to deliver more certain results, advertising is getting squeezed out of the budget. In addition, brand managers and agencies sometimes hurt their own cause by using intuitive rather than quantitative (recall testing, ad tracking studies, and so forth) arguments to justify advertising to tnanagement. As one manager said: "Trade spending brings this high degree of certainty: M paid for this drug. It gets my volume up 20%'...compared to rationalizing, understanding, and selling to senior management the power of advertising ideas. The whole 36 U2JO.2 Difficulty assessing the profitability of trade spending. SOLUTIONS: • Use single-source data and market models. • Measure profitability. • Track retailers' performance and hold them accountable. Although it is fairly easy to assess volume gains from trade promotion spending (via supemiarket scanner data, for example), it is more difficult to measure the profit impact of trade dollars. The use of single-source data linking media exposure to purchase behavior and sophisticated models can help a firm evaluate (1) how responsive sales are to different types of trade promotion spending, (2) the prof- IMRKETINO mmBEMENl Escaping the Catch'22 of Trade Promotion Spending itability of trade proniolions. and (3) ways to cut trade spending without huiling retailers or manufacturers. For example, one firm in our study found that response to a temporary price reduction for a particular product was 15%-20%, whereas response to an in-ad promotion or display was as high as 20()%. Manufacturers can use such results to convince retailers to accept fewer trade dollars and spend them differently. One manager said her firm cut trade spending 25% in the last three years; of that amount, spending on deal decreased 60%. "It wasn't until we were able to demonstrate to them [retailers] over time that it wasn't the price reduction that was moving the volume at retail, it was the merchandising activity, and that difference [in volume] was ten-fold," she said. However, in the absence of single-source data, it is often difficult to track the profitability of trade promotions. According to a 1990 Harvard Business Review article by M.M. Abraham and Leonard Lodish, only 16% of trade promotion events are profitable (based on incremental sales of brands). Managers should evaluate trade sjjending as a percentage of revenue, dollars spent per case, or percase revenue, rather than on a 100-case/volume basis. In addition to using scanner and single-source data and calculating profitability, manufacturers could do a better job of tracking retailers' performance and holding them accountable for effectiveness and results in trade spending. A common complaint from executives is that although they may see temporary increases in trade buying from a price concession to the trade, the spending is wasted because consumer sales volume doesn't change. Retailers frequently "forward buy." and tbey inventory merchandise purchased on deal, subsequently selling to consumers at full price and buying less of the manufacturer's nonpromotional output. These executives bluntly refer to trade promotions as •"retail subsidies" and '"bribes." For example, when allowances are given to retailers, they tnay load up on the prcKluct and sell it at lull price later. In tracking retailer performance, managers should monitor retail pass-through rates—tbe percent of product bought on deal that also is sold to the consumer on deal. For example, one manager in our study found that his competitor shipped 90% of its product on deal, but only 22% was bought on deal by the consumer—the rest was forward-buy. (In a forward-buy, the retailer stockpiles product bought on deal to avoid buying at full price later.) However, the manager's company shipped only 50% of its items on deal, and its pass-through to the consumer was 19%. So this firm was much more efficient on the trade side, selling less product on deal with a comparable pass-through rate. Hence, it either had more money to spend or was more profitable. What managers should be asking is. for every dollar spent, what is gained—dollars in and dollars out. Many managers might be asking this question, but it is clear that the answers are sometimes difficult to obtain or off-limiis politically because of the various reward systems for managers, as we discuss shortly. PROBLEM: Financial pressures create a sliort-temi focus. SOLUTIONS: • Increase the time horizon. • Reduce trade spending gradually. Managers face increased demands to deliver "bottotn line'" perfomiance. particularly in firms involved in mergers and acquisitions. Many brand managers hinted at threats of termination if they did not deliver financial targets. As one manager said: "If you're behind in your numbers...and volume is your objective, it's very easy to trade in the advertising | for trade promotions], just throw another deal out there and Oy some more cases into the trade warehouse." In addition to focusing on fmancials, brand managers also see a connection between profit and plant utilization. A firms* desire to keep plants operating at high levels contributes to pressure on managers to increase promotional spending (to gain short-tenn boosts in volume). Tactics such as these often displace a focus on other, more long-term issues, including long-term market development. In addition, focusing on financials in the current period can cause problems in subsequent periixls. For example, one sales manager said her company would offer large trade allowances at the end ofthe year to sell excess product. Even though the company made its numbers for that period, it got off to a slow start in the next period because trade inventories were very high. Increasing managers' time horizons to a two-tofour year planning period is easier said than done. Current financial needs often are more pressing than long-tenn planning needs. However, enduring brand strength requires a iong-temi focus. One manager commented: "1 think the change has to come from top management. The more enlightened ones will set up long-term programs and then stick with them. Long tenn takes courage." One way to ease into a long-tenn focus is to reduce trade spending gradually over the course of several years, rather than take a drastic reduction in '. I No. 2 37 any current period. For example, otie firm's goal was lo get lo the point where factory sales equaled consumer sales in any specific time period. It wanted to eliminate forward-buying and ensure that retailer purchases ended up on consumer rather than warehouse shelves. Rather than biting the bullet in a one-year time period, the company gradually reduced trade spending over a three-year period. "We want to use the minimum dollars necessary to generate retail support and then use the rest of the money to drive consumer advertising," said a manager of the firm. "Our feeling was that we were spending too heavily against the trade over the last four to five years. We were determined to get back into the branding of the business and get the message out to the consumer," Another manager said its firm started cutting the depth of its allowances and reducing the number of protnotions each year. Once that was accomplished, it repealed the process over a two-to-three Additional Reading year time period. Managers, salespeople, and retailers won't balk at such reductions if their compensation systems are adjusted accordingly. For exatnple, sales quotas should be gradually reduced in proportion to trade spending. Salespeople are happy to have reduced targets and the tools to make their numbers over a 52-week period, rather than forcing retailers to buy product at the last minute each quarter. And trade custotners don't like to buy excess inventory-—they have lo store it and manage il. Retailers also will be happy with the concept of spreading sales evenly over the year because many are moving toward just-in-time delivery. They wouldn't have to pay inventory bonuses lo their buyers, either. The short-term focus on financial performance also is related to the nature of compensation systems. Managers are responsible for short-term earnings, and it is unlikely that a manager who is evaluated monthly and quarterly will take a longterm perspective. PROBLEM: Abraham, M.M. and L.M, Lodish (1990). "Getting the Most Out of Advertising and Promotion," Harvard ss Review, (May-June), 50-60. Sales pressures to maintain trade protnotion spending. SOLUTIONS: • Modify evaluation and reward systems Buzzell, R,D,, J.A. Quelch. and W.J. Salmon (1990). "The Costly Bargain of Trade Promotion," Harvard Business Review, (March-April), I4t-49, • Include sales managers in the planning process. • Add trade managers. Farris. P,W. and J,A, Quelch (1987), "In Defense of Price Promotion," Sloan Matiai^ement Review, (Fall) 63-9. Jones, John P. (1990), "The Double Jeopardy of Sales Promotions," Harvard Business Review, (SeptemberOctober). 145-52. Low, George S, and Jakki J. Mohr (1992), The Advertisin}>-Sales Pvomoiion Trade-ojf: Theory and Practice, Report #92-127. Cambridge, MA; Marketing Science Institute. Parsons, Andrew J. (1992), "Focus and Squeeze: Consumer Marketing in the '90s," Marketing Management, I (Winter), 50-5. Quelch, John A. (1983), "It's Time to Make Trade Promotion More Productive," Hatvard Business Review, (May-June), 130-36. ., S.A. Neslin, and L.B. Olson (1987), "Opportu•L nities and Risks of Durable Goods Promotion," Sloan Management Review, (Winter). 27-38. 38 Vol. 2Jo. 2 Volume movement is still ihc basis of evaluation and compensation for many retailers, as well as for salespeople. Such compensation methods overtook the fact that increases in volume, if attributable to heavy promotional discounts, may add very little to the bottom line. In fact, in some instances, the incremental profit frotn gains in volutTie can be negative. However, brand managers often are accountable for some combination of profit and volume/share goals. The manufacturer's brand/product managers have to show steady gains in revenue from period to period. This inconsistency in compensation systems and the use of differential criteria for brand and sales managers lead to a conflict over the best way to achieve goals. The manufacturer's own employees, therefore, may be hampering each other's efforts to achieve organizational objectives. Sales managers wbo use trade promotions t<» reach their volume goals can thwart the profitability and revenue goals of brand managers. Firms can alleviate the problem by modifying evaluation systems for salespeople to include the UARKETING MANAmm Escaping the Catch-22 of Trade Promotion Spending incremental profits from volume gains; and evaluation criteria must be unifonn for brand and sales managers. For example, some firms evaluate sales managers—and even trade members— on the basis of profitability. One manager commented: "One of the things...we are doing at the moment is...allocating more points to more profitable volume. So that, in essence, the salesperson is getting rewarded on profit, even though he or she doesn't know it. So if we make $4 on one package and $1 on another and they are both one pound, [the salesperson's] points are roughly four to one." The salesperson who is 20% behind forecast for the quarter probably is not interested in the fact that a great, new ad campaign will be rolled out in four months. He or she needs some way to sell more product to retail customers and make the quota. These salespeople often make a compelling and immediate case for increasing trade spending rather than waiting for the uncertain gains from a new ad campaign, in fact, the brand managers with whom we spoke said the sales staff is a huge political force that is a natural factor for increasing promotions. Cuts in Irade spending may mean cuts in commissions and bonuses for salespeople. Some firms are solving the problem by including sales managers in the brand mix planning process, not only to get their input, but also to get their commitment to the resulting allocation. One manager said: "Our chief sales guy and I had a tremendous working relationship; he was part of the thinking and learning process all the way through, and he understood we couldn't keep this incredible level of spending forever. It definitely helped, not only to get his depth of experience, but to get his ownership of the plan." Other firms are adding trade promotion managers, who work with the sales force and regional sales managers to determine the specific needs for trade dollars. Trade managers plan specific trade activities and can help allocate fund.s and spend them. For example, if a firm wants 10 features per year or a certain percentage of display space, it can evaluate the trade manager not only on achieving these goals, but also on the costs required to attain them, volume gains, incremental sales, and the resulting profits. Revamping compensation systems, involving salespeople, and hiring trade managers all can help alleviate sales pressures to maintain unreasonable levels of trade spending. One brand manager in our survey said that two sales managers at his firm were vociferous in their arguments against trade reductions: tbey felt they were being cheated out of making their quota. Howev- er, these same managers came back a year later to apologize because the brand manager's program bad worked—sales based on new advertising were strong, and margins were high. The systemic causes of trade promotion escalation still exist. Even though managers recognize the causes and problems associated with trade spending, they also have not been able lo bring it under control. Marketers of consumer goods may find that, by implementing the solutions proposed here, they may be less subject to the whims, vagaries, and demands of the retail trade. And retailers may see the advantages of working with manufacturers that position themselves on quality products and services. Reduced levels of trade spending will be inevitable in the future. Ultimately, the marketing war will be won on great selling ideas, great products, and strong consumer loyalty—not on spiraling trade spending. |ZQ About the Authors Jakki J. Mohr is an Assistant Professor of Marketing in tbe Graduate School of Business Administration at tbe University of Colorado-Boulder. She has worked in advertising at Hewlett-Packard and other computer firms. She conducts studies on the effect of organizational characteristics on managerial decisions and communication behaviors in organizational relationships. Her research has been funded by the Marketing Science Institute and published in the Journal of Marketing and the Strategic Management Journal. She won tbe Frascona Teaching Excellence Award for younger faculty at her university in 1992, and she does consulting work in the hightechnology/computer industry. George S. Low is a PhD candidate in marketing at the University of Colorado-Boulder. He has worked in advertising as a media planner, and his research interests are in the area of integrated marketing communication management. He has received grants from the Marketing Science Institute and his article. "Brand Management and the Brand Manager System: A Critical-Historical Evaluation," will be published in 1994 in a special issue of the Jotsrnal of Marketing Research on brand management.