Transparency Enhancing Technology

Transparency Enhancing

Technology

Computers, Consumers, and Consent

Innis Walker

Master of Laws in Law and Information Technology, Course D Thesis

Stockholm University

Supervisor: Christine Kirchberger

All rights reserved by the author. For use contact: inniswalker-at-googlemail.com.

Version 1. May 2013.

Spring 2013

Contents

Prologue: a picture of the past and a vision for the future ................................................................... 3

Methodology .................................................................................................................................... 4

Setting the scene: App functionality ................................................................................................ 5

Act I: The Need for Transparency – law and principles ...................................................................... 6

1.

Seller liability under English Common Law of contract .............................................................. 6

1.1

The doctrine of notice: are terms brought to consumer’s attention? ....................................... 6

1.2

TED and 21 st

century notice.................................................................................................... 7

2.

Seller liability under consumer legislation .................................................................................... 8

2.1

Unfair Terms (Articles 3, 4 and Annex to UTD) .................................................................... 9

2.2

Transparency of language and contracting environment (Article 5, UTD) .......................... 11

2.3

Misleading act or omission (Articles 6 and 7, UCPD) ......................................................... 12

2.4

Generally unfair commercial practice (Article 5, UCPD) .................................................... 15

2.5

Conclusions regarding seller liability ................................................................................... 16

3.

Arguments of Principle ............................................................................................................... 16

3.1

Promoting party autonomy.................................................................................................... 16

3.2

Economic principles .............................................................................................................. 19

3.3

Access to justice .................................................................................................................... 21

3.4

Conclusions regarding arguments of principle ..................................................................... 23

Act II: Some challenges of implementing a technological solution to a legal problem .................... 25

1.

Retrieval of contract data ............................................................................................................ 25

1.1.

Recognising terms displayed on page .................................................................................. 25

1.2.

Retrieving linked terms ........................................................................................................ 26

1.3.

Websites without obviously linked terms ............................................................................ 26

1.4.

The wider context of term retrieval functionality ................................................................ 26

2.

Identifying “key” terms ............................................................................................................... 28

2.1.

Ranked list prepared in advance by humans ........................................................................ 28

2.2.

Computer-executed ranking: Designing rules for determining rank order .......................... 29

1

2.3.

Harnessing the strength of the machine: Probability, machine learning, and big data ........ 29

2.4.

Knowing when to display “key” terms ................................................................................ 31

3.

Translation .................................................................................................................................. 32

3.1.

The pros: Legal language as a cooperative subject for translation ...................................... 32

3.2.

Contextual meaning: the challenge of automating translation ............................................. 33

3.3.

Further challenges in defining meaning: Fuzzy terms v solid rules .................................... 35

3.4.

Machine learning and statistical prediction as a solution? ................................................... 35

Act III: Final reflections on TED ....................................................................................................... 37

BIBLIOGRAPHY .............................................................................................................................. 39

Books ............................................................................................................................................. 39

Articles ........................................................................................................................................... 39

Cases (EU, UK, USA).................................................................................................................... 42

EU Legislation ............................................................................................................................... 43

UK Legislation ............................................................................................................................... 43

Policy Documents .......................................................................................................................... 43

Online resources ............................................................................................................................. 44

Contract terms ................................................................................................................................ 45

Personal Correspondences ............................................................................................................. 45

Annexed documents ....................................................................................................................... 46

2

Prologue: a picture of the past and a vision for the future

Being a consumer has changed since advent of the Internet. We perhaps frequent virtual storefronts more than physical ones, enter into contracts more than ever before (almost every visit to a website involves a contract of some sort, perhaps unwittingly), and often agree to terms we do not read.

Unfortunately, the default rules that govern contractual relationships have not matched the pace of technological progress. In this thesis I shall demonstrate that these rules lag behind our technological reality, that this faltering harms consumers, sellers, and societies alike, and that a solution is not beyond our grasp. I achieve this by considering (Act I) specific areas of online seller liability partly arising from the gaps between laws and technical reality and how such gaps also curb the achievement of jurisprudential and social objectives. After considering these factors, I will then

(Act II) exemplify one possible solution in which technology bridges the trenches it has dug.

Whereas technology currently enslaves consumers, it can empower them; whereas technology currently disenfranchises consumers, it can emancipate them; whereas technology currently confounds consumers, it can enlighten them; we only need bid it do so. As this thesis demonstrates, our technological past need not be our future.

Consumers face an increasingly difficult task contracting online. A recent study reported that just reading all the privacy policies (not even terms and conditions of sale/use) which consumers are subjected to would take around 201 hours per year at a cost to the average US Internet user of

$3,534 annually

1

. This issue of overwhelming volume is compounded by the complexity of the reading involved – with comparable Flesch-Kincaid scores to that of a scientific journal, comprehendible (broadly) only to those who read at college level or higher

2

. Furthermore, contracts are growing in length

3

, further impeding self-interested consumers.

At the same time, technology has developed from fixed-line dial-up to mobile broadband, from the limited search engines of old to accurate, predictive search engines built on a multitude of sensory inputs which sketch the user’s search profile

4

. We live in the era of big data, where companies and computer programs map user behaviour to offer functionality, services, and adverts adapted to that user. So why is the platform for consumer contracting stuck in the mid-90s? Why is the technology deployed in consumer contracting no more complex than HTML in its simplest form?

1

A McDonald & L Cranor, ‘The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies’, (2008) 4 I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the

Information Society 543; M Masnick, ‘To Read All of the Privacy Policies You Encounter, You ‘d Need to Take a

Month Off From Work Each Year’, TechDirt, http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20120420/10560418585/to-read-allprivacy-policies-you-encounter-youd-need-to-take-month-off-work-each-year.shtml

2

F Marotta-Wurgler & R Taylor, ‘Set in Stone? Change and innovation in consumer standard-form contracts’, (2013)

New York University Law Review 240 at 253

3

Ibid

4

See e.g. E Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you . ( London: Viking: 2011)

3

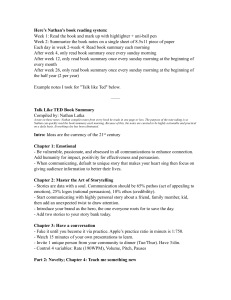

Methodology

Objective of the paper: The aim of this thesis is to demonstrate a need and explore one potential avenue for developing browser-based technology to assist consumers in discovering and understanding seller’s standard terms. For ease, this transparency-enhancing technology shall be called TED. First, legal, economic and normative factors shall be considered in demonstrating a need for such technology, often by comparing current practice to a perfect world and hence how

TED could improve this dissonance. Implementation exploration shall consider information retrieval, ranking of term importance, and knowledge acquisition for translation functions as well as how TED might function in its technical environment.

Limitations on topic: This thesis shall only address online consumer contracts made on standard terms, i.e. pre-drafted contracts prepared by sellers acting in the course of trade and presented to civilians acting outside of their trade in a purely consumptive capacity in transactions made via the

Internet.

Research methodology: Need is explored through exposition of liability for sellers under both classical contract law and contemporary consumer law via standard legal research methods. More academic, principle-based arguments draw from a combination of academic legal sources and author insights. In completing the thesis, implementation was researched through a combination of academic legal informatics sources and also through correspondence with some IT experts.

Target audience: This thesis targets online sellers and regulators as predominant gears of change.

To a large extent, support of both of these parties will determine the fate of such technology.

Consumer credit providers can also play an important role in pressurizing sellers to change habits.

Limitations of the analysis: Undertaking a broad, all-inclusive analysis risks superficially addressing some debates worthy of deeper analysis. As an interdisciplinary analysis, it may betray the author’s lack of in-depth technical education. Hence, advice was sought on technological issues from qualified professionals. Lastly, TED pursues legal perfection in e-contracting; rather than legal sufficiency via myths that only perpetuate the legal dissonance. Should courts take a more facilitative view of the law, this might undermine the analysis; however, simply exposing these situations might also be an important function for this thesis.

4

Setting the scene: App functionality

Before addressing the need for TED and some developmental aspects, a brief explanation of its functionality and business environment is required. TED shall offer two separate, equally important functionalities: firstly, TED retrieves and analyses the terms of agreement, highlighting terms likely to be unpleasant, surprising, or influential to the consumer. TED does not seek to narrow the consumer’s judgement in these matters, but rather augments the consumer’s vision, enabling them to fully appreciate the true nature of the bargain – particularly where it diverges from their wishes or expectations. These terms are, with no effort on the consumer’s part, placed in a predominant spot in their web-browser at the appropriate point in the contracting process to offer a bona fide opportunity to examine “key” terms.

But simply highlighting is not enough: consumers are also at a knowledge disadvantage

5

, so TED seeks to augment consumers’ ability to understand the terms of their agreement. In doing so, TED must offer explanations of not just legal words, but also plain language contextualization of whole phrases or terms. This could be facilitated by the homogenizing effect of standard terms usage in consumer contracts, examined in depth later on. However, it should be noted that this standardization may be faltering, and time will tell whether truly standard term contracts continue to be the pervasive norm

6

. Again, translation should be seen as augmented fact-gathering rather than providing any form of legal advice to the consumer. Whilst translation necessarily imbues the definition with some form of the author’s bias at the expense of reader’s autonomy, TED challenges autonomy no more than if the consumer were to consult a legal dictionary, and perhaps TED’s potential for learning and self-development through collection of training data from a wide base of sources offers a less biased platform than that of a standard legal dictionary.

As a business model, TED would be best managed as a non-profit – since its objectives are primarily social and it needs to be seen as seller-neutral. This is not to say that TED could not generate income. In its initial stages, TED could seek government funding as a social initiative.

Alternatively, TED could offer certification of transparency to sellers – i.e. that their contract is readable and translatable by TED, thus enables consumers as regards contractual transparency – in return for a fee and seller cooperation. This would gain traction if heavily supported by government campaigns and demanded by consumer groups and consumer credit providers CCPs, perhaps forcing de facto industry acceptance of TED and TED Certification. CCPs could also be targeted for funding, as the technology clearly benefits them (see later). Costs could be minimized by seeking

5

J Maxeiner, ‘Standard Terms Contracting in the Global Electronic Age: European alternatives’, (2003) 28 Yale

Journal of International Law 109 at 136; B Keirsbilck, ‘The Interaction Between Consumer Protection Rules on Unfair

Contract Terms and Unfair Commercial Practices’, (2013) 50 Common Market Law Review 247 at 252

6

Correspondence with Florencia Marotta-Wurgler of 17/05/2013

5

pro bono advice from UK lawyers, and perhaps gathering click data for the identification of “key” terms and complex translation via a computer game aimed at lawyers. Hence, whilst a non-profit setup enables TED’s impartiality, it need not solely leech off state funding. And over time, as TED increasingly gathers click data – perhaps from new sources such as the game suggested above– the initially high start-up investments in legal advice and programme development will likely decline, as TED becomes increasingly self-sufficient and capable of gathering data through lower cost methods (e.g. through the game). TED is a 21 st

century answer to a 20 th

century legal problem; a technological solution for the constraints of the flesh, which could help propel consumers into a more commercially-aware network society.

Act I: The Need for Transparency – law and principles

The need for transparency shall be considered thusly: (1) Seller liability under contract at Common

Law; (2) Seller liability under consumer law; and (3) Reasons of principle (predominantly academic arguments with a wider social perspective) for supporting development of TED.

1.

Seller liability under English Common Law of contract

1.1

The doctrine of notice: are terms brought to consumer’s attention?

Incorporation of standard terms is usually achieved by sellers in the contracting process via checkbox, or presenting an “I agree” button with a statement. However under English common law, the doctrine of notice requires that particularly onerous or usual terms be brought to the consumer’s attention

7

. Further, notice must be determined for each term independently; the more undesirable or irregular the term, the more a seller must do to bring that specific term into the consumer’s attention

8

. For the most egregious of terms this may even require the term be “printed in red ink with a red hand pointing to it”

9

. Lady Hale confirmed that this continues to represent the position in the 21 st

century, that each term must be weighed individually along a gradated scale of notice

10

.

Thus sellers wishing to incorporate their terms into consumer agreements must be aware that the more detrimental or unexpected the individual term is, the more overt their act of notification must be. Although the modern trend may be to challenge such terms on the grounds of unfairness rather

7

Interfoto Picture Library v Stiletto Visual Programmes Ltd [1989] QB 433 at 436-437, as per Dillon LJ

8

Ibid at 443C, as per Bingham, LJ.

9

Spurling v Bradshaw [1956] 1 WLR 461 at 466, as per Denning, LJ (obiter); cited in Interfoto v Stietto at 436-437

10

O’Brien v MGN [2002] CLC 33 at 39-40 (para 22-23)

6

than non-incorporation

11

, O’Brien confirmed that the doctrine of reasonable notice continues to apply in light of developments in consumer law

12

.

1.2

TED and 21

st

century notice

But does the modern consumer contracting environment match the notice requirements based on an individual assessment of how onerous or surprising each term is to a consumer? Where Facebook would have a consumer agree to licence out all IPRs over their content royalty-free on Facebook’s behalf

13

, how surprising or onerous is this? And is a miniscule link to terms at the foot of the page

“extraordinary” enough highlight that specific term? Does the addition of an “I agree” checkbox before the link really increase this visibility of one term over another? Is it enough even to provide the full terms in a plaintext box on that page for the user to scroll through prior to clicking an “I agree” button, with no term highlighting or red hand pointing to specific terms as envisioned by

Lord Denning

14

? Furthermore, given the earlier statistics about the cost (time and money) of reading all privacy policies alone, can we seriously be surprised if consumers do not read all the terms? And if not, what effect does this have on how surprising such terms ought to be? Perhaps, the test then ought to be what the reasonable consumer might speculate?

Some might argue that under classical contract law, a party’s signature on a contract’s face bound them to terms therein, even if not read

15

. However, (1) is clicking “I accept” really the same as a signature? (2) Is the ‘signature’ really on the ‘face’ of the contract as the terms are likely stored in a different digital location? And (3) how applicable are draconian classical principles in our modern consumer-oriented contract law system

16

? L’Estrange is nearly 100 years old, yet the doctrine of notice was confirmed in 2001

17

. Thus presuming we reject this thread of argument, it is questionable whether online sellers currently do enough to bring terms to the attention of consumers and thus incorporate their terms. Although this online incorporation has not been tested per se in the

11

C Riefa & J Hörnle, ‘The Changing Face of Electronic Consumer Contracts’, in L Edwards & C Waelde (eds.), Law and the Internet , (3. ed.) (Oxford: Hart: 2011) at 111

12

E.g. Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977, Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999, and the Consumer

Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008.

13

See s.2 ‘Sharing Your Content and Information’ in Facebook’s Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, 2012, http://www.facebook.com/legal/terms

14

15

Spurling v Bradshaw

C Riefa & J Hörnle at 109; citing L’Estrange v Graucob Ltd [1934] 2 KB 394.

16

R Brownsword & G Howells, ‘When Surfers Start To Shop: Internet commerce and contract law’, (1999) 19 Legal

Studies 287 at 292; J Spencer, ‘Signature, Consent, and the rule in L’Estrange v. Graucob’, [1973] 32(1) Cambridge

Law Journal 104; and recently in E Peden & J Carter, ‘Incorporation of Terms by Signature: L’Estrange rules’ (2006)

21 Journal of Contract Law 96

17

O’Brien v MGN [2001] EWCA Civ 1279

7

UK since Beta v Adobe

18

, sellers should not mistake non-engagement on the part of the court with active endorsement. Courts and regulators, for their part, perhaps also ought to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the conflicting law in this area.

Without legal clarification, sellers should beware of liability in this area and seek to avoid this through risk averse solutions – such as TED – which help avoid liability before it arises. This is achieved by making onerous or unexpected terms particularly visible to consumers at the appropriate point in the contracting process. But perhaps even providing the full text on the page immediately prior to contracting may not be enough to distinguish one particularly onerous term from another. TED can solve this by separating such terms from the body of the contract, making them prominently and separately visible. Sellers then ought to be protected against future claims of non-incorporation due to lack of reasonable notice, satisfying the courts at little comparative expense. Had the automated ticket dispenser in Thornton

19

presented such a notice to the consumer, or the sellers in Interfoto suggested to the consumers that they might wish to check over clauses X,

Y, and Z, the court ought to have found in the seller’s favour instead. And comparatively, these measures would cost little to bona fide companies operating without deceitful intention. Is the lowcost preventive solution surely not a better choice than the expensive remedial one?

2.

Seller liability under consumer legislation

Online sellers might also be open to liability under consumer protection rules regarding unfair contract terms or those prohibiting unfair commercial practices. These two regimes have an interesting interplay, which cannot be fully explored in this thesis. But as Keirsbilck demonstrates, a finding of unfairness under one regime ought not ipso facto mean unfairness under the other; rather that the grounds for such a finding under one regime often involve similar considerations of fact and circumstance as under the other, thus influencing assessment under the latter

20

. A consumer can be widely defined as “a person acting outside of their trade or profession”, thus excluding merchants acting in a personal capacity, but including hobbyists who make a profit from trading in their hobbies

21

. The following seller behaviour may prompt liability: (1) Defining the content of obligations – most obviously influences the relationship; (2) Language choices in contract drafting

– can enable or impede consumer understanding; (3) Contract presentation choices –display and

18

Beta Computers (Europe) Ltd v Adobe Systems (Europe) Ltd 1996 SLT 604

19

Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking Ltd [1971] 2 QB 163

20

B Keirsbilck at 253-254; Case C-453/10, Perenicova and Perenic v SOS Financ spol sr.o

at 42-46

21

J Puplava, ‘Use and Enforceability of Electronic Contracting’ (2007) 16 Michigan State Journal of International Law

153 at 185

8

structure of terms influences their transparency; and (4) Designing of contracting environments – can facilitate or hinder contractual transparency. These may influence the following heads of claim:

1.

Unfairness of contract terms (93/13/EEC

22

, Arts. 3 and 4; UK UTCC

23

Regulations 1999,

Regs. 5 and 6)

2.

Lack of linguistic or contextual transparency (93/13/EEC, Art. 5; UK UTCC Regulations

1999, Reg. 7)

3.

Misleading act or omission (2005/29/EC

24

, Arts. 6 and 7; UK CPUT

25

Regulations 2008,

Reg. 5 and 6)

4.

Generally unfair commercial practice (2005/29/EC, Art. 5; UK CPUT Regulations 2008,

Reg. 3)

2.1

Unfair Terms (Articles 3, 4 and Annex to UTD)

Two sub-heads of claim may be relevant herein: (A) terms deemed unfair on examination; (B) terms presumed unfair unless proven otherwise.

A) Article 3 UTD – Standard terms which imbalance rights and obligations to detriment of the consumer

Terms drafted in advance by sellers

26

which run contrary to “good standards of commercial morality and practice” relating to both the substance and presentation of the terms

27

, and which significantly disadvantage the consumer as regards their rights and obligations vis-à-vis the seller under the contract are likely to be considered unfair terms

28

. The “good faith” and “significant disadvantage” should be considered separately, but overlap again to some degree

29

. Should a term fall outside of this definition, it may still be open to question under the general test for unfairness

30

.

Since consumer contracts are likely to fall within Article 3 by virtue of Article 3(2), the general test need only be raised, not discussed at length.

22

Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993 on unfair terms in consumer contracts (UTD)

23

Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999, No. 2083

24

Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning unfair business-toconsumer practices in the internal market (UCPD)

25

26

Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, No. 1277

27

UTD Art. 3(2), UTCCR Reg. 5(2)

Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank [2001] UKHL 52, at para 13-17; Office of Fair Trading, OFT

311, ‘Unfair Contract Terms Guidance: Guidance for the unfair terms in consumer contracts “regulations 1999’, Sept

2008, available at http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/unfair_contract_terms/oft311.pdf at 9

28

29

UTD Art. 3(1); UTCCR Reg. 5(1)

Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank at para 37

30

Art. 4, UTD; Reg. 6, UTCCR

9

In most online consumer environments, expediency, ease of use, and economy

31

have prompted sellers to draft terms in advance and present consumers with these as a take-it-or-leave-it part of the offer of the product (contract-as-product)

32

. Hence, terms which offer sellers significant benefits at the expense of the consumer (where this contradicts principles of moral business practice) are liable to be struck out by a court. Particularly where these terms limit a seller’s fiscal responsibility, e.g. as regards consequential losses to the consumer or third parties, losing the protection of such clauses could precipitate significant consequential liability for a seller.

TED can certainly play a role in reducing this potential for liability by increasing the transparency of consumer contracting. Sellers who could demonstrate that their website actively supports TED’s transparency-enhancing features – which increase the visibility of terms so consumers become aware and offer alternative explanations so that consumers can become informed – could surely help convince a court that the requirements of commercial morality and practice have, in fact, been met; and thus the seller should not be held liable. Sellers also ought to beware of the danger of viral effects poisoning their terms as a result of their reuse of standard terms. Due to such reuse (of linguistic expressions and whole terms in pursuit of economy and legal stability

33

), a single judgement striking down a single term in a single contract might be clearly felt many miles from its legal epicentre. Should the term be examined by a court under the general rules for unfairness, demonstrating that the seller invested in certification of and cooperation with transparencyenhancing measures could surely go a long way towards demonstrating the circumstances of the contract’s conclusion were fair, and the consumer ought to be bound by their decision, particularly where a market for substitutes exists? Lastly, as shall be discussed later in the “arguments of principle”, forgiving seller liability where consumers are properly informed of the existence of such terms, and then choose to ignore such a warning, is perhaps more appropriate than seller liability, as it more accurately embodies the principle of autonomy which underpins contract law.

B) Annex (i) UTD – Grey-listed practices - Standard terms and irrevocability

The legislation also provides an indicative, non-exhaustive list of types of term which are likely to be considered unfair

34

. In particular, (i) prohibits: “irrevocably binding the consumer to terms with which he had no real opportunity of becoming acquainted before the conclusion of the contract”.

31

G Howells & S Weatherill, Consumer Protection Law . (2 nd

ed.) (Aldershot: Ashgate: 2005) at 19

32

M J Radin, ‘Humans, computers, and binding commitment’, (2000) 75 Indiana Law Journal 1125 at 1126; J Nehf,

‘BOOK REVIEW: European Fair Trading Law: The unfair commercial practices directive’ (2007) 35 International

Journal of Legal Information 305 at 306-307

33

M J Radin at 1150; G Howells & S Weatherill at 19

34

Annex; UTCCR 1999, Schedule 2

10

This appears to differ from the sentiment of Article 3 only in so far as the first two words,

“irrevocably binding”. Given the operation of mandatory cooling off periods

35

, can consumer contracts really be said to be “irrevocably binding”, particularly given that many sellers will happily process returns for goods in resale condition – although this lacks a unilateral power of revocation on the seller’s part. But in any case, it may provide another head of claim under which an aggrieved might exploit to force a seller to endure a perhaps costly legal battle. TED offers a quick and simple way to dispatch any lingering doubts, ensuring the consumer is presented with ample opportunity to become acquainted with the terms and their meaning prior to clicking “I agree”; avoiding seller liability thereunder.

2.2

Transparency of language and contracting environment (Article 5, UTD)

Sellers must also draft terms transparently, in plain, intelligible language

36

and giving the consumer the chance to examine all the terms

37

. Doing their best under the circumstances will not be enough

38

. Intelligibility is to be judged as read by a consumer, not a lawyer

39

and need not entail a complete understanding of every word but at least the opportunity to appraise themselves of the terms prior to contracting so they do not come as a surprise

40

.Sellers must ensure both linguistic clarity and wider transparency of the contracting process to avoid liability thereunder

41

.

Many online retailers are likely to be guilty of failing to ensure that, widely defined, their contracting documents and environments attain what is a high standard for transparency under the

UTD. Besides notice-based-arguments regarding visibility of terms, the language of much of standard terms contracting is still dense, verbose ‘legalese’

42

– although there is some indication that this may be changing, at least amongst privacy policies

43

. Despite linguistic changes, policy length may provide arguably as strong a deterrent

44

. Hence, perhaps even if presented with the terms, the consumer does not truly have the opportunity to engage with them on an equal academic footing.

35

Article 9, Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on consumer rights

36

37

Art. 5, UTD; Reg. 7, UTCCR

Recital 20

38

See the language of Article 5 – use of the imperative, “must always be”

39

OFT 311 at 10

40

Ibid at 87 (19.9)

41

Ibid at 86 (19.8); Law Commission/Scottish Law Commission, ‘Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts: Advice to the department of business, innovation and skills’ March 2013 available http://lawcommission.justice.gov.uk/docs/unfair_terms_in_consumer_contracts_advice_summary-web.pdf at ss.33-34

42

43

F Marotta-Wurgler & R Taylor at 253

Correspondence with F Marotta-Wurgler of 17/05/2013 – regarding her forthcoming article on the subject.

44

F Marotta-Wurgler & R Taylor at 253

11

It is precisely these shortcomings that TED seeks to address. Linguistic clarity is addressed by the translation functionality, augmenting the consumer’s own legal knowledge with TED’s ability to translate single words or phrases they do not understand, or even putting the effects of the whole term in context to help the consumer understand how it applies to them. Arguably, the evolution of legal language has preferred legal certainty at the expense of generic readability/comprehensibility; stability over simplicity

45

. Perhaps it is even the case that some level of verbosity and linguistic complexity is required to repel future legal challenge

46

. If this is true, TED may be able to provide a unique bridge between the lawyer’s quest for stability and the regulator’s quest for informed consumption, acting as a legal babel fish and allowing both to coexist. TED also better enables wider transparency by highlighting important terms and providing visible, easy access for consumers to contract terms prior to contracting. Given the decreasing visual real estate in which modern consumer contracting environments operate, ensuring that contract terms are displayed effectively but concisely should surely be of concern for sellers and regulators alike. Ensuring a profitable and consumer-equitable future for electronic contracting is important for all parties involved, and thus TED’s functionalities will perhaps become only more important over time.

2.3

Misleading act or omission (Articles 6 and 7, UCPD)

Despite sharing a similar nexus

47

, the UCPD is perhaps wider than the UTD, including sellers’

(‘traders’) behaviour towards the consumer in the contracting process beyond simply unfairness of the terms. However, its high expectations for a well-informed, reasonably circumspect, average consumer may fail to reflect the reality of consumer behaviour, leaving the UCPD comparatively toothless

48

. A question to be considered throughout this subsection is: What separates an act or an omission? Is the display of a link to contract terms at the foot of the page an act or a failure to act enough (omission)? For completeness, this thesis argues both perspectives in the alternative.

A) Misleading Acts (Article 6, UCPD)

45

C Williams, ‘Legal English and Plain Language: an introduction’, (2004) 1 ESP Across Cultures 111

46

Ibid

47

B Keirsbilck; S Orlando, ‘The Use of Unfair Contractual Terms as an Unfair Commercial Practice’, (2011) 7(1)

European Review of Contract Law 25

48

H Micklitz, ‘The General Clause on Unfair Practices’, in G Howells, H Micklitz, & T Wilhelmsson, European Fair

Trading Law . (Aldershot: Ashgate: 2006) at 111; T Wilhelmsson, ‘Misleading Practices’, in G Howells, Micklitz, & T

Wilhelmsson, European Fair Trading Law . (Aldershot: Ashgate: 2006) at 131-135; J Trzaskowski, ‘User-Generated

Marketing – Legal Implications When Word-of-Mouth Goes Viral’, (2011) 19(4) International Journal of Law and

Information Technology 348 at 375-376

12

A seller who provides information likely to deceive the “average consumer”

49

as to their rights or risks under the contract or as to the rights/obligations of the seller, is likely liable for misleading behaviour where the consumer’s behaviour is altered

50

. Online sellers engage in the act of providing information in various forms: they (vicariously) choose the language for their contract terms, they

(vicariously) choose the content and structure of the contract terms, and importantly they design the environment for contracting, within which information about the bargain is exchanged – each of which may be grounds for liability where it influences consumer behaviour.

As described above, perhaps the choice to use verbose ‘legalese’ is not a choice per se but a requirement for successful contract design. However this does not absolve the seller of their responsibilities under Article 6, UCPD. Thus, they remain liable to the extent that the chosen language deceives the consumer as to the effect of the term and influences their behaviour. As stated before, TED can help facilitate coexistence of the lawyer’s need for term certainty and the regulator’s expectation that the consumer not be misled by term language or its misunderstanding.

This is achieved by offering a translative functionality which the consumer can draw upon to clarify their reading and understanding of a given term. The seller’s choice of term structure and presentation may also mislead a consumer. For example, key information may be “hidden in plain sight” amongst a dense jungle of other terms, or provided only as a sub-clause rather than a standalone term (highlighting its importance). TED counteracts this by analysing the contract and presenting consumers with key terms in a separate, highly visible, easily-digestible window overlaid upon the final agreement page – where the consumer is most likely to engage with the information.

Key terms are highlighted from the noise, rather than hidden within it.

Orlando advances an interesting argument regarding the overlap of unfair terms and misleading acts: a seller who includes a term which they know or ought to have known to be unfair engages in a deceptive act since, despite being de jure unenforceable, such terms usually fool unsuspecting, trusting consumers into de facto compliance

51

. To the extent that consumer contracts contain terms like Facebook’s surreptitious attempt to insert the grant of a royalty-free, assignable licence in their favour over users’ media

52

, one is forced to conclude that at least some sellers are knowledgeable and willing participants and ought to be liable based on Orlando’s conceptualization. Although TED is not intended to furnish consumers with legal advice about clause enforceability, by bringing the

“key” clauses to consumers’ attention and offering translation into layman’s terms TED hopefully increases the chances that consumers will become aware of such clauses, triggering a common

49

See Article 2(k) for definition of average consumer; with problems described above

50

Article 6(1), Article 6(1)(c), Article 6(1)(f), Article 6(1)(g), UCPD; Reg. 5(2), Reg. 5(4),CPUTR

51

S Orlando at 261

52

s.2 ‘Sharing Your Content and Information’ in Facebook’s Statement of Rights and Responsibilities

13

sense reaction against such ‘unfair’ terms. Perhaps for sellers, supporting TED might act as an indication of good faith intention not to deceive – thus where such unenforceable terms slip through the gaps, sellers can perhaps avoid Orlando’s argument by disproving constructive knowledge.

Since constructive knowledge is essentially a balancing act, demonstrating a policy of openness and support for a transparent contracting platform could surely help contribute to this end.

Lastly, choices made by sellers when constructing the contracting environment, such as whether to make specific reference to the contract terms with a checkbox signifying assent and whether this box is pre-ticked, may also deceive a consumer by disguising the importance of consumers reading and understanding these terms. Redesigning the entire electronic contracting environment could be a cumbersome task with the potential to upset consumers used to prior shopping habits. Supporting

TED, on the other hand, is a much easier way to help ensure that potentially deceptive website design is tolerated by courts on the grounds that the seller has acted to rectify this, by supporting the implementation of technology which helps make terms more visible and comprehendible to the average consumer, whereas ‘deception’ implies absence of bona fides is required on the part of the seller. Thus, TED can acts to the seller’s benefit by offering mitigating circumstances where sellers might otherwise be liable for providing misleading information; demonstrating that where such misleading information was disclosed, the seller did this unintentionally and in good faith, and therefore damages ought to be mitigated.

B) Misleading Omissions (Article 7, UCPD)

Whereas the above subsection argued that sellers make active choices to provide consumers with misleading information, this subsection considers the flipside of the coin: sellers perhaps do not do enough to positively deceive the consumer, but have omitted, hidden, or provided unintelligibly or ambiguously, material information that the average consumer needs to make an informed decision in context

53

. Online shops for mobile devices might be offered some leeway given their reduced visual real estate in which to convey all the necessary information

54

. “Materiality” includes both that the information is required to make an informed decision

55

(which will vary with product and

53

Article 7, UCPD; Regulation 6, CPUTR

54

Ibid; Office of Fair Trading, OFT 1008, ‘Consumer Protection From Unfair Trading: Guidance on the UK regulations

(May 2008) implementing the unfair commercial practices directive’, (2008) at 35 (7.19)

55

Recital 14, UCPD

14

medium

56

), and materiality in terms of its actual effect on consumer behavior

57

. Similarly to the

ECD, sellers are also required to provide minimum information in invitations to treat

58

.

For our purposes, sellers may omit material information by omitting material content or by failing to appropriately communicate included content. Seller liability for omission of content would include things such as failing to describe important aspects of the product or provide all the terms of agreement, but these are not within the purview of TED’s application as they are perhaps less commonplace issues. Rather, TED primarily addresses the problem of omissions in communication, where the seller provides the consumer with information, but in a non-transparent way which makes it difficult for the consumer to gather and comprehend all the facts upon which their decision will be based. For example, non-transparent drafting of the contract might omit important warnings about the effect of terms required by the average consumer to understand precisely how onerous the clause is, or drown out important terms in amongst a sea of small print. Ambiguous or unintelligible contract language could also trigger seller liability to the extent the consumer cannot understand its meaning. Additionally, failing to display the links to contract information in a clear and transparent manner might also have deleterious effects for seller liability.

TED tackles these communication breakdowns by implementing new channels for transmission of this information. Increased visibility of key terms ensures consumers are aware of “material” terms.

Offering literal and contextual translation compounds this effect by ensuring that data transmitted to the consumer becomes information via its being understood, thus avoiding liability on grounds of lack of linguistic clarity. Particularly where courts have discretion, sellers demonstrating protransparency behaviour, such as supporting TED’s implementation, might be able to tip this balance in their favour.

2.4

Generally unfair commercial practice (Article 5, UCPD)

Given the preceding analysis of seller liability under the specific rules regarding misleading acts and omissions, application of the general prohibition shall not be discussed at length. It suffices for our purposes to note that while courts seem to implicitly accept current click-wrap/browse-wrap as not “contravening the requirements of professional diligence”

59

, technological development might

56

OFT 1008 at Ibid at 33 (7.16), 37 (7.33); H Collins, ‘Harmonization By Example: EU laws on unfair commercial practices’, (2010) 73(1) Modern Law Review 89 at 107

57

58

H Collins at 106

Article 7(4), UCPD; Reg. 6(4), CPUTR

59

Article 5(2), UCPD; Reg. 3(3), CPUTR. See Beta v Adobe

15

be expected to influence these standards, perhaps leaving those who fail to engage with transparency-enhancing technology open to future liability.

2.5

Conclusions regarding seller liability

Sellers must therefore beware of the risk under English common law that their terms will not be incorporated, and also that incorporated terms may be struck down under contemporary consumer law on account of unfairness or lack of transparency. Furthermore, sellers should also be wary of liability under unfair commercial practices legislation as a result of active choices in term, contract, and website design, and also where they fail to provide the consumer with the appropriate information required to make their decision. TED was presented as a potential solution for each.

Whilst the preceding section discussed a need for TED from the practical perspective of seller liability, the proceeding section shall take a more academic perspective, demonstrating how new technology can better reconcile some of the underlying objectives of our legal system.

3.

Arguments of Principle

3.1

Promoting party autonomy

A) TED helps overcome the challenges of classical autonomy

Autonomy, a central pillar of English contract law, classically adhered to strict free market principles, allowing parties to contract with whomever they like, on terms of their own choosing

60

.

Courts would not interfere in contracting beyond determining whether a “meeting of minds” had occurred between the parties

61

. Responsibility for preventing morally reprehensible contract terms was placed on consumer’s shoulders ( caveat emptor ), on the grounds that consumers were better placed to protect their interests than courts on their behalf

62

– similar to contemporary US courts’ position

63

. The essence of classical autonomy was that contracting parties made their own decisions.

As argued above, in the online context it is doubtful whether the classical “meeting of minds” can truly be established: consumers rarely read and are unlikely to understand the terms upon which they are supposedly agreeing. TED may offer a solution to the meeting of minds dilemma: by making the terms of agreement more visible and offering explanations of clause meaning, it

60

Ibid

61

G Howells & R Schultze, Modernising and Harmonising Consumer Contract Law . (Munich: Sellier European Law

Publications: 2009) at 89; P Atiyah, The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract . (Oxford: Oxford University Press:

1979) at 681 in R Brownsword & G Howells at 292

62

63

G Howells & R Schultze at 90; G Howells & S Weatherill at 15

J Winn & B Bix, ‘Diverging Perspectives on Electronic Contracting in the US and EU’ (2006) 54 Cleveland State

Law Review 175 at 184

16

counteracts the forces in modern e-contracting environments which debilitate consumer autonomy.

By putting the parties on more equal informational footing, consumers are given the tools to truly achieve caveat emptor : and, where consumers choose to ignore this opportunity, perhaps they should rightly be bound by the terms of their agreement.

B) Consumer protection as autonomy 2.0?

On the surface, paternalistic consumer protection legislation would appear to contradict classical contract law, interfering with sanctity of contract and reallocating the responsibility of caveat emptor . But might this change actually represent a redefinition of autonomy

64

, sensitive to modern morality or modern technological environments?

At a minimum [autonomy now requires] a kno wing understanding of what one is doing in a context in which it is actually possible for one to do other wise, and an affirmative action in doing something, rather than a merely passive acquiescence in accepting something. These indicia translate into requirements that terms be understood, that alternatives be available, and probably that bargaining be possible.”65

Although over 10 years old, these comments remain as true today as when first written. Normative shift might offer one explanation for the expansion of “autonomy”

66

; the legal response to the philosophical question, what does making a decision entail? Such an explanation could be supported by following the developments in the doctrine of notice in the 20 th

century; emerging from a narrow rule applicable in only a few cases to a broad rule, generally applicable

67

. As

Savirimuthu acknowledges “traditional ideas like agreement, autonomy, and consent cannot remain unaffected by the increasing interaction between technology, law, and society”

68

. Alternatively, technological changes may have prompted the need for legal development via their effect on the contracting environment. Modern e-commerce has put consumers at a twofold disadvantage: knowledge and leverage (bargaining position)

69

, although perhaps informational deficit leads to lack of leverage rather than acting separately

70

. Terms go unread

71

, are perhaps out of the reader’s

64

One definition could be “free, informed, and undistorted choice”: G Howells & R Schultze at 90

65

M J Radin at 1125-1126

66

J Savirimuthu, ‘Online Contract Formation: Taking technological infrastructure seriously’, (2005) 2 University of

Ottawa Law & Technology Journal 105 at 120

67

Harris v Great Western Railway (1876) 1 QBD 515; Parker v South Eastern Railway (1877) 2 CPD 41; Spurling v

Bradshaw [1956] 1 WLR 461; Thornton v Shoe Lane Parking ; Interfoto Picture Library v Stiletto Visual Programmes

Ltd ; O’Brien v MGN

68

69

G Howells & R Schultze at 116

70

J Maxeiner at 136 citing Ocean Grupo Editorial SA v Rocio Murciano Quintero , 2000 ECR I-4931 at I-4973J

The “lemons equilibrium” reduces bargaining power in markets with uninformed consumers as they must presume all products to be equal and thus their decision is solely dictated by price: M J Radin at 1149 citing G Akerlof, ‘The Market

17

competency

72

or committable time

73

, and are presented in take-it-or-leave-it, contract-as-product form

74

: hardly a platform for autonomy. Consumer law, then, may be the counterbalance in the consumer –seller relationship, equalizing the knowledge disadvantage, creating a more transparent ground from which autonomy can flourish. In both cases, it is submitted that contemporary consumer legislation is not at odds with classical autonomy, but an attempt to locate it in today’s moral and technical environment.

C) TED and 21 st

century autonomy

If contemporary autonomy is founded on moral evolution, we now believe that information is key to autonomy. TED highlights the existence of important terms from the contract, so consumers ought to be aware of at least the key aspects of the bargain. TED also helps less academically able consumers understand the language and effect of the terms, increasing all consumers’ ability to play an active role in their contracting life. TED facilitates a transparent and easy flow of contractual information between seller and consumer in pursuit of a better informed choice.

As regards overcoming the challenges posed by technical change, technology can also assist here.

Arguably, developers even have a moral responsibility to contribute to solving a problem aggravated by their implementations of technical solutions

75

. By presenting key terms in an obvious way, TED helps raise consumer awareness of terms’ existence, hopefully prompting them to be read. It also streamlines the process by highlighting only the most important from a consumer perspective. TED also augments reader competency by offering translation and explanation of words, phrases, and terms. Unfortunately, TED will not force sellers to offer space for term negotiation. However, in a truly transparent market, consumers are perhaps best placed to demand change, taking advantage of their role in the market forces

76

.

Lastly, TED may offer a more autonomy-supportive remedy than consumer protection. Is it not more autonomous to enable the consumer to protect themselves rather than pick up the pieces behind them? If sellers dictating the terms of the contract violates consumer autonomy, surely having courts do so violates the autonomy of both parties, perhaps submitting the consumer to a

For “Lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism’, (1970) 84 Quarterly Journal of Economics 488 at 490-

491

71

Correspondence with Pär Lannerö, founder of Common Terms project, 21/05/2013

72

F Marotta-Wurgler at 253

73

Ibid

74

M J Radin at 1155; J Savirimuthu at 128

75

J Savirimuthu at 127; L Lessig, Code: Version 2.0

. (New York: Basic Books: 2006)

76

See footnote 70

18

double violation

77

. TED acts ex ante , aiding autonomous decision making by consumers by giving them the right informational tools to do the job instead of imposing a fair bargain after the fact.

Furthermore, treating the symptoms (as in ex post facto solutions) simply perpetuates the cycle. Is it not better for autonomy to teach consumers how to fish than feed them for a day? TED not only involves less interference with consumer autonomy than court redress, but it also may be more efficient in the long run if it can solve the problem. TED may also lead to a fairer contracting environment: should consumers who have the awareness and capacity, but not the motivation, to read the terms be protected? Should their laziness be rewarded with their escaping from contractual obligations?

3.2

Economic principles

Under English contract law, economics and contract law are inseparably intertwined. Contract law evolved as an instrument of market planning

78

and as a platform for ensuring secure dealings so that commerce could prosper

79

. Therefore, considering TED and its influence in its market context is an important feature of a complete analysis, and given the increasing power of major commercial actors, demonstrating wider economic benefits might be crucial to TED’s gaining market traction.

A) Cost-effectiveness

Sellers are usually driven by the reduction of losses and the pursuit of gain. Some avenues of potential loss have already been explored in depth: legal liability can prompt significant financial loss in terms of the resources (manpower, infrastructure, and legal advice) needed to field responses to claims as well as the potential cost of unenforceable contract clauses, settlement fees, or damages. Additionally, beyond the immediately dissatisfied customers, bad publicity (as a result of the legal actions require to either enforce or escape rights or obligations towards the consumers) might jeopardize the seller’s brand, and deter future customers. By pursuing the objective of maximum transparency in the contracting process, TED helps sellers meet their obligations under contract and consumer law. Where TED cannot fully avoid seller liability, it can at least demonstrate their good faith and consumer’s disinterest which may influence the court in a seller’s

77

M J Radin at 1158; R Craswell, ‘ Redmedies When Contracts Lack Consent: autonomy and institutional competence’,

(1996) 30 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 209 at 232

78

P Atiyah, The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract . (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1979) at 681; R Brownsword

& G Howells at 292

79

R Brownsword & G Howells at 292-294; G Howells & S Weatherill at 10;

19

favour. This could help develop positive brand recognition: a seller who positively supports transparent contracting ought to be more trustworthy, a trait valued by online consumers

80

.

To regulators, cost effectiveness could have a micro and a macro meaning: firstly, costeffectiveness of government through streamlining bureaucratic public services

81

via increased citizen responsibility; and secondly, reduction of wasteful consumption in an already strained economic environment. Significant amounts of money are invested in organisations which to varying extents act as ex post facto remedial services for aggrieved consumers. This cost could be minimized if consumers played a more active role in their contractual life, rejecting terms or contracts they felt were disingenuous or overly onerous; and as has been advocated, TED may provide consumers with additional tools to inform themselves. Furthermore, by helping consumers to inform themselves, TED also helps reduce wasteful spending on (contract-as-) products which ultimately dissatisfy the consumer and cause a rift between them and the seller. Uninformed consumption solely benefits the exploitative seller, and only in the short term. Good faith sellers, willing to admit their (contract-as-) product’s shortcomings, may be disadvantaged if bad faith sellers can disguise poorer quality products amongst the background noise of e-commerce.

Ultimately, money spent here is wasteful consumption, as it leaves the consumer dissatisfied and does not stimulate positive market competition. Then, more money is wasted on remedying the situation via complaint and legal recourse; more fruitless spending to return only to the status quo.

TED can help consumers separate the sellers likely to offer good quality products and service from mendacious sellers likely to deploy exploitative terms or policies, thus helping consumers make smart choices. Hopefully in doing so, TED saves consumers the money which might have been wasted on substandard products and saves both parties time, energy, and money spent pursuing remedial action – economic resources which could be used more effectively elsewhere.

B) Consumer Credit Providers

Under certain circumstances, consumer credit providers (CCPs) such as Visa or Mastercard will be liable to refund aggrieved consumers on behalf of sellers who utilize their services

82

. In distance transactions where sellers may be hard to find, or located outside the consumer’s jurisdiction, CCPs may increasingly stand to foot the bill. TED can help avoid the situation by highlighting important

80

J Savirimuthu at 133 – quoting EC Commission, ‘E-Commerce in Europe: Results of the pilot surveys carried out in

2001 ’, Eurostat 2002, http://europa.eu.int/comm/enterprise/ict/studies/lr-e-comm-in-eur-2011.pdf at 36

81

E.g. courts and large consumer standards and consumer advice bodies such as the Office of Fair Trading, whose net operating cost was £61m for 2011-2012: Office of Fair Trading, ‘Cash flow’, http://www.oft.gov.uk/about-theoft/annual-plan-and-report/annual-report/#.UYdm3bVmiSo

82

Consumer Credit Act 1974, s. 75, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/39/section/75

20

contract features the consumer should read, and offering explanations of meaning. This in turn should reduce situations where (contract-as-) products do not meet consumer expectations, and thus form the basis of a chargeback. Since CCPs make up the fabric of communication between the financial and online retail worlds, their leverage may provide a useful pinch-point through which seller cooperation (with TED’s implementers) can be promoted or even forced

83

, so long as the benefit can be conveyed to CCPs. Thus, in protecting themselves, CCPs could contribute to creating a more stable contracting environment – for the benefit of consumers, bona fide businesses, and regulators alike.

C) Predictability of relations, market stability, and transparency

Perhaps linked to macro cost-effectiveness, one important aim of contract law is predictability of commercial relationships, and ultimately market stability

84

. Latent, undiscovered terms jeopardize market stability; should they come to light, hidden terms may jeopardize performance of the contract, upon which others might be relying

85

. The relationship is no longer predictable as a result of the contract; but rather the contract becomes the site of unpredictability in the relationship.

Furthermore, depending on the pervasiveness of standardization in contract terminology, a single judgement against a single term could have sizeable ripple effects

86

. Whilst TED cannot necessarily guard entirely against judicial intervention, it can significantly alter the current contracting environment to reduce instances where judicial intervention would be justified; concomitantly increasing the prima facie reliability of e-contracts, and thus the stability and predictability of legal relationships. Above all, an informed consumer is usually a happy consumer; and if they have no reason to complain, the relationship remains stable. TED could thus be a useful tool in promoting market stability.

3.3

Access to justice

Simply having rules is unfortunately not enough to ensure consumers are treated fairly, hence the need for judicial enforcers. Both the UTD and the UPCD require “adequate and effective” means of redress to be available

87

, and the concept of “access to justice” will be familiar to many legal

83

Consider how CCPs imposed of certain information security standards upon sellers: R Epstein & T Brown,

‘SYMPOSIUM: SURVEILLANCE: Cybersecurity in the Payment Card Industry’, (2008) 75 University of Chicago

Law Review 203

84

G Howells & S Weatherill at 10; P Atiyah at 681, R Brownsword & G Howells at 292-294

85

Ibid

86

As Bragg v. Linden Research, Inc.

, 487 F. Supp. 2d 593 (E.D.Penn. 2007) prompted further challenges such as

Feldman v Google Inc.

, 513 F. Supp. 2d 229, 231 (E.D. Pa. 2007)

87

Article 7(1), UTD; Article 11(1), UPCD

21

systems. But consumers may be strongly deterred from seeking redress due to: (a) a lack of legal knowledge; or (b) perceived circumstantial barriers which work in the sellers favour.

A) Using TED to bridge the knowledge gap

A legal knowledge gap develops when a consumer does not know: (i) the legal rules, and thus if their rights have been breached; or (ii) how to enforce their breached rights

88

. How many consumers

(or even lawyers) are fully aware of the rules of commerce within their own state? Furthermore, ecommerce aggravates this problem as transactions are potentially transnational, introducing complex issues such as jurisdiction and choice of law, not to mention knowledge of a separate legal system. What does it imply for the adequacy of redress if one is never aware that redress might be appropriate? Even if a consumer knows their rights, do they know how to enforce them? Is the responsibility to inform the public met by a government website posting plain text legislation on or offering simplified explanations regarding the effect of the law or responses to frequently asked questions? Furthermore, it would seem appropriate to consider not only users’ linguistic literacy but also their technical literacy: Is it OK to rely on the Internet as a means of providing access to justice given highly variable rates of computer literacy within a population? And does this prejudice certain classes, age groups, or races?

TED can help mitigate the effects of the knowledge gap by reducing the need for knowledge of the laws and legal system. Consumers who make informed transactional decisions (in a market for substitutes) should hopefully be satisfied with their agreement, as it is based on transparency in bargaining. Where they are satisfied, there is hopefully no need for legal recourse. TED does not so much bridge the knowledge gap as sidestep it, but to a disadvantaged consumer perhaps even this much is progress.

B) Barriers to suit

Even where the knowledge gap is bridged, consumers may be dissuaded from seeking recourse by

(a) a perceived imbalance between the consumer and the seller in terms of finances and legal experience, or (b) a discouraging assessment of the costs and benefits. In both cases, consumer perception of reality is key, as it is this that influences their decision to pursue legal claims.

88

See e.g. E Rubin, ‘The Internet, Consumer Protection and Practical Knowledge’, in J Winn (ed), Consumer

Protection in the Age of the 'Information Economy. (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006)

22

A consumer who has grounds for a claim against a seller might think it futile to pursue a seller who

(the consumer perceives) can throw vast amounts of wealth and manpower at the case, and who has easy access to high-quality legal advice. Particularly in the case of large, powerful, online multinational such as Amazon or Play.com, consumers may believe their own resources to be outmanned and outgunned from the get go, causing an effective barrier to their obtaining justice.

Another barrier which may deter consumers might be that the potential benefits of redress are outweighed by the costs of doing so (widely defined). Given the relatively low transaction sums involved, particularly when compared to the cost of a single hour of legal counsel, the financial rewards are likely to be low. Furthermore, a consumer must invest significant time and energy in this endeavour, in addition to their money. Once they get over the initial vexation, consumers are likely to be quick to value their energy and time over the menial transaction sums. Consumers of online services may also worry that should they seek legal redress, their service shall be suspended: which may be an intolerable consequence for most Facebook users.

TED helps sidestep these issues by removing the need for legal recourse. Handing the consumer increased transactional knowledge (and hence power) at the bargaining stage enables consumers to make smart choices, which should hopefully avoid conflicts arising. At this stage, the seller’s size or reputation ought not to influence whether their terms are acceptable to a consumer, offering easier access to contractual justice, widely defined. Furthermore, comparatively little investment is needed (compared to that required to pursue legal action)

89

, therefore TED ought to be preferred to ex post facto remedial solutions.

3.4

Conclusions regarding arguments of principle

In sum, this chapter has argued that regulators ought to take note of technological solutions to attaining the objectives of contract law, party autonomy, and economic predictability. Furthermore, such technology may provide a more effective means of achieving these principles than solely relying on legal enforcement of consumers’ rights or sellers’ obligations, offering a means of resolving the conflict before it has even begun; one which is more easily accessible to consumers and offers less deterrence against its use. Lastly, such technology could have economic benefits for sellers, CCPs, and governments, reducing wasteful consumption which benefits neither party in the long run and drains the resources of governments, CCPs, and private parties alike. In these ways, transparency-enhancing technology (in the form of TED) can be seen to be broadly beneficial, and

89

Although it has been argued that even reading every set of terms a consumer is presented with may be a challenge of its own.

23

offer a potentially complementary function to the legal rules and systems already in place. It offers a 21 st

century solution to a problem which really should be consigned to the 20 th

century.

24

Act II: Some challenges of implementing a technological solution to a legal problem

Whilst the preceding chapter addressed the need for transparency-enhancing technology and the benefits of the suggested implementation (TED), the proceeding chapter discusses some potential challenges in its implementation under these three broad categories: (1) Retrieval of contract data;

(2) Identification of “key” clauses; (3) Translation.

1.

Retrieval of contract data

TED may need to retrieve contract terms in varying circumstances

90

: (1) Terms displayed in full on the acceptance page; (2) Terms linked (via explicit reference, or unreferenced at foot); (3) Terms not displayed or obviously linked.

1.1.

Recognising terms displayed on page

Document markup might be one way a computer could identify if contract terms are displayed on a page

91

. This may include a header name which includes one of certain indicative words (Terms,

Conditions, Policy, etc.) or a large body of similarly, but uniquely, formatted text, perhaps in its own dialogue box. Furthermore, formatting continuity could be supported if a search revealed repeated use of common legal terms like “liability”, “indemnity”, or “contract”. The presence of these factors should be sought to ensure accuracy in identification. A way to improve accuracy in

TED’s infancy could be to employ a moderator to oversee the success of this recognition function, whilst also offering sellers some way to verbalize objections if they feel TED is wrongly flagging content on their site.

A further challenge will be ensuring that all relevant terms are captured, as even if the terms of sale are displayed prominently, other terms, e.g. privacy and cookie policies, may additionally bind consumers, but not be part of those terms immediately displayed. Perhaps the most efficient way to maximize recall in this case is to proceed to search for linked terms as if none were displayed in full on the page (see below), then ignore any resulting retrieved terms which are duplicated. Although this increases the potential for false positives, perhaps completeness to the extent of repetition ought to be preferred over possibly overlooking any key clauses.

90

Correspondence with Jenny Eriksson Lundström, 07/05/2013

91

Correspondence with Pär Lannerö, founder of Common Terms project, 21/05/2013

25

1.2.

Retrieving linked terms

It is perhaps more common in modern e-commerce to provide a link to the terms rather than present them in full on the page

92

. This includes both a situation where they are clearly brought to the consumer’s attention (often via a statement plus checkbox indicating assent

93

) and the situation where it is not (e.g. on Facebook where the links are just placed at the foot of the page). Therefore

TED must be able to recognise and follow such links in order to retrieve the terms for assessment.

To address this, TED could undertake a search of outbound links with internal references on the acceptance page (for retailers; on the signup page for service providers) for those with certain indicative words such as “Terms”, “Conditions”, “Privacy”, and variations on a theme. Once a link was identified as relevant, a script would then have to be developed that would allow TED to follow it and retrieve specific data from the destination. Methods similar to those in the previous subsection could then be deployed to determine what text is relevant (i.e. comprises contract terms) at the destination. Header, footer, sidebar and link text could be identified via document markup and discarded, whilst similarly, uniquely formatted body text could be retrieved as potential contract terms. A moderator could be employed for oversight until it was clear TED could function predominantly error-free.

1.3.

Websites without obviously linked terms

TED may struggle here without significant further development. But perhaps the solution lies in acceptance of shortcomings: the fact that terms cannot be easily identified using standard offline thinking (supplemented with some automated capabilities) may be the mark of an untrustworthy seller. For sincere sellers the resultant threat of brand/reputation harm might encourage website redesign with a more transparent platform, assisting TED in the process, and regarding sellers who do not change, it highlights behaviour of which consumers should be wary

94

.

1.4.

The wider context of term retrieval functionality

TED is intended to operate as an add-on for standard web browsers. Hence, data storage and required processing power are likely to be important considerations. Few consumers will want to wait 30 minutes to download a huge add-on or clog up valuable hard disk space that could be spent

92

C Witner, ‘The Rap on Clickwrap: how procedural unconscionability is threatening the e-commerce marketplace’,

(2008) 18(1) Widener Law Journal 260

93

94

J Savirimuthu at127-133

On consumer trust see e.g. P Beatty, I Reay, D Scott & L Miller, ‘Consumer Trust in E-Commerce Web Sites’,

(2011) 43(3) ACM Computing Surveys1 (036600300)

26

on movies. Nor will they continue to use the application if it leaves insufficient processor power for streaming the newest episode of Drop Dead Diva . Thus designers should try to focus on solutions which sap minimal storage space and processing power from the user.

One solution is to take a centralized approach; centralizing both data storage and term analysis, with the browser add-on acting mainly as a conduit. TED could externally mine data for contract terms in advance, storing and processing these on TED’s servers, and then supply the information to the consumer’s browser upon request from the add-on. The add-on would run in the background at all times, but only be active under certain circumstances (when the agreement page triggers TED’s

“launch”). This avoids clogging the user’s computer with contract data and algorithms for identification and analysis, and also passes processing burden on to TED’s servers. A downside of this approach might be that without effective version control, TED could be providing outdated advice depending on when terms were last retrieved. One solution perhaps could be to compare

“last edited” dates on TED and seller’s files to highlight such instances and prompt re-retrieval.

Alternatively, the TED add-on could scan for contract terms every time a consumer visits a seller’s site and pass the retrieved contract data back to TED’s servers. Although it ensures that the most up to date version of the terms are those being analysed, it might generate unnecessarily high volumes of Internet traffic and processing. Given the potential number of websites which a user might access daily (and which might contain some form of contract terms), this could quickly consume limited mobile data allowances or limited bandwidth, slowing user’s Web surfing to a crawl. Furthermore, it would require a higher level of continuous processing, again to the detriment of less technologically-advanced users or mobile users. Finally, on a macro level, if TED were to become a staple of consumer life implementing this policy, it would likely generate much unnecessary Web traffic. Amazon.co.uk receives around 3 606 558 daily visits

95

, and its terms were last updated

05/09/2012

96

. At the point of writing (05/06/2013) TED’s version would have been updated 984

590 334 times, with no changes made. This is to the detriment of all parties involved. Hence, term retrieval TED-server-side would be preferable, particularly if some form of version control was implemented.

95

Amazon.co.uk website report, HypeStat, http://amazon.co.uk.hypestat.com/

96

Conditions of Use and Sale, Amazon (UK), http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/help/customer/display.html/ref=footer_cou?ie=UTF8&nodeId=1040616

27

2.

Identifying “key” terms