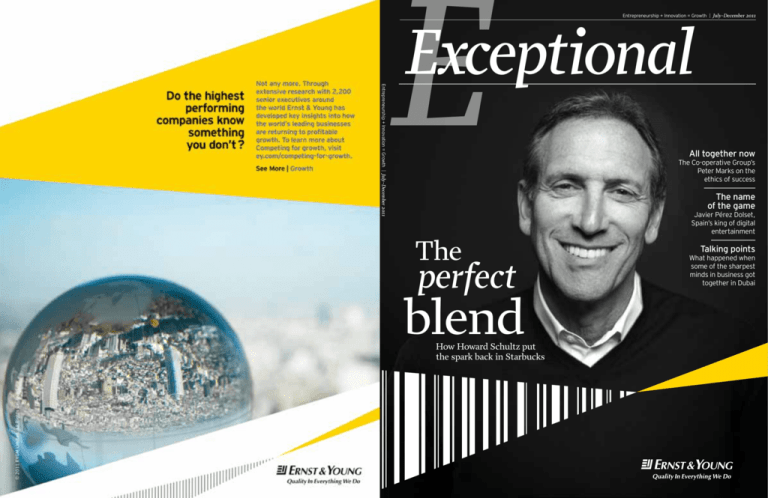

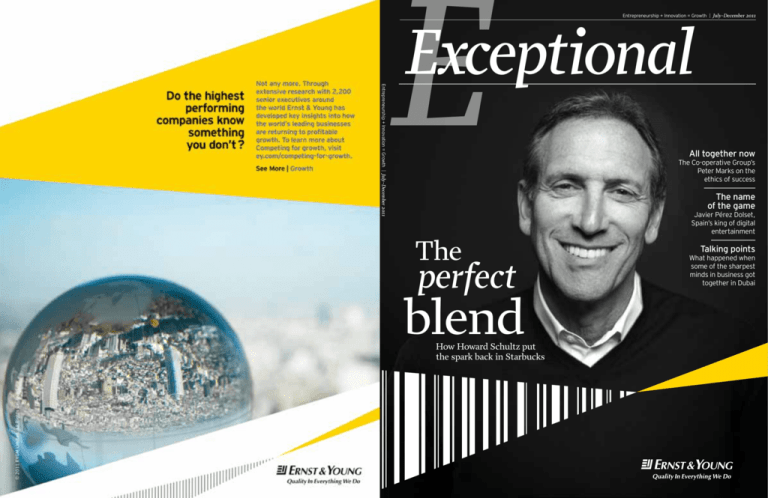

Entrepreneurship + Innovation = Growth | July-December 2011

E

Entrepreneurship + Innovation = Growth | July-December 2011

Exceptional

All together now

The Co-operative Group’s

Peter Marks on the

ethics of success

The name

of the game

The

perfect

Javier Pérez Dolset,

Spain’s king of digital

entertainment

Talking points

What happened when

some of the sharpest

minds in business got

together in Dubai

blend

How Howard Schultz put

the spark back in Starbucks

e

W

Welcome

Editor Molly Bennett

Assistant Editor Laura Evans

Senior Designer Lynn Jones

Art Director Rachel Creane

Picture Editor Johanna Ward

Design Director Ben Barrett

Production Gary Chambers

Account Director Emma King

Production Director John Faulkner

Managing Director Claire Oldfield

CEO Martin MacConnol

For Ernst & Young

Marketing Director, SGM, EMEIA Penny Cooper

Senior Marketing Executive, SGM, EMEIA

Victoria Howell-Richardson

Exceptional is published on behalf of Ernst & Young by

Wardour, Walmar House, 296 Regent Street, London

W1B 3AW, United Kingdom. Tel +44 (0)20 7016

2555 www.wardour.co.uk Exceptional is printed

by Newnorth.

For further information on Exceptional, please

contact Victoria Howell-Richardson at +44 (0)20

7980 0285 or victoria.howell-richardson@uk.ey.com

Ernst & Young

Assurance | Tax | Transactions | Advisory

About Ernst & Young

You’ve probably noticed that Exceptional has a new, livelier look and feel.

We think it reflects the colorful personalities and diverse experiences

featured inside the magazine and hope you agree.

What does it take for a company to have “staying power”? Should we only

apply the term to those that have been around for many decades, or does it

have a broader application? Longevity matters, of course: with age comes

wisdom, and with wisdom comes the ability to take a step back and view the

business in the context of history, using this knowledge to adapt to changing

economic and market dynamics.

But even relatively new companies can have staying power. Perhaps

they’ve spotted a gap in the market that will bear fruit for years to come.

Or maybe they signed up to a company charter that guarantees its values

will be upheld no matter who is at the helm. Businesses with staying power

keep one eye on the spreadsheets and the other on the future. It’s about

continually looking for ways to solidify your base and reach ever higher.

One company that combines all these traits is Starbucks, which has made

the journey from a small Seattle coffee shop to one of the world’s most

Ernst & Young is a global leader in assurance, tax,

transaction and advisory services. Worldwide, our

141,000 people are united by our shared values and

an unwavering commitment to quality. We make a

difference by helping our people, our clients and our

wider communities achieve their potential.

recognizable brands. As the company celebrates its 40th anniversary,

Ernst & Young refers to the global organization of

member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of

which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global

Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not

provide services to clients. For more information about

our organization, please visit ey.com

Marlies van Wijhe takes us on a tour of Van Wijhe Verf, a family business

CEO Howard Schultz tells us how he’s turning the company around.

We also speak to Javier Pérez Dolset, founder of Grupo Zed, who has

taken advantage of the ballooning market for web and mobile apps. And

that has stayed independent in a sector of huge multinationals.

Sustainability is key to having staying power. Wally and Debbie Fry of Fry

Group Foods tell us how their vegetarian products can

© 2011 EYGM Limited. All Rights Reserved.

make a positive impact on the planet, and Henrik Fisker

Cover photography John Keatley/Redux

EYG no. CY0164.

of Fisker Automotive explains why “energy efficient” and

This publication contains information in summary form

and is therefore intended for general guidance only.

It is not intended to be a substitute for detailed research

or the exercise of professional judgment. Neither

EYGM Limited nor any other member of the global

Ernst & Young organization can accept any responsibility

for loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining

from action as a result of any material in this publication.

On any specific matter, reference should be made to the

appropriate advisor.

“luxury” don’t have to be mutually exclusive terms.

We also visit the Ernst & Young EMEIA Entrepreneur

Of The Year Forum in Dubai, where some of the world’s

top business leaders — and a criminal profiler — met to

exchange notes on operating in today’s global marketplace.

This is just a taster of what’s inside. I hope you enjoy

The opinions of third parties set out in this publication are

not necessarily the opinions of the global Ernst & Young

organization or its member firms. Moreover, they should be

viewed in the context of the time they were expressed.

In line with Ernst & Young’s commitment to minimize

its impact on the environment, this document has been

printed on paper with a high recycled content.

your new-look Exceptional.

Julie Teigland

Strategic Growth Markets Leader,

EMEIA,

Ernst & Young

Exceptional July–December 2011

1

C

Contents

04

12

Profiles

Heart and soul

Starbucks’ founder,

Howard Schultz, explains

how he brought the

global chain back from

the brink

Streets ahead

The Co-operative Group

sticks to a strong ethical

code — and, says CEO

Peter Marks, this has

stood it in good stead

during the recession

26

30

The view from here

From Brick Lane to

the heart of the City:

brokerage firm Execution

Noble’s Nick Finegold

explains why he hooked

up with a Portuguese

investment bank

Unguilty pleasure

38

In living color

42

Ethical edibles

The days of slow, boring

electric cars are over.

Meet Henrik Fisker, who

is on a mission to make

sustainable driving sexy

We talk to Marlies van

Wijhe, who represents

the fourth generation to

run Dutch paint company

Van Wijhe Verf

From Fry Group Foods’

base near Durban, South

Africa, Wally and Debbie

Fry are raising awareness

of the environmental

impact of meat

“To be an entrepreneur

is to be a gamer. It’s a

challenge. We confront

the unknown every day”

Javier Pérez Dolset, CEO of Spanish video game

company Grupo Zed

Exceptional July–December 2011

30 38

52

Analysis

22

2

12

48

52

60

Northern light

From 2 hotels to 170

(and counting):

Petter Stordalen on

Nordic Choice Hotels’

exponential growth

across northern Europe

A greener cleaner

The L’Arbre Vert

eco-cleaning brand is

going global, says Michel

Leuthy, CEO of its parent

company, Novamex

Banking on change

Kazakhstan’s banking

sector, like many other

nations’, went through

a period of turmoil. The

head of the country’s

National Bank, Grigory

Marchenko, explains how

he solved the problem

18

36

46

56

The difference

defines us

Using Ernst & Young

research, criminal

profiler Thomas

Müller asks whether

entrepreneurs are

a breed apart

Chain reaction

Franchises are eternally

popular, but can they

be considered to be

entrepreneurial?

Leading

the charge

We report from

Ernst & Young’s

Entrepreneur Of The

Year Forum in Dubai

A shifting balance

of power

Regulars

01

Welcome

10

Agenda

62

Doing

business in …

64

Beyond profit

An introduction

to the exceptional

entrepreneurs featured

in this issue

Events, programs

and research from

Ernst & Young that will

help your business grow

Tax, cultural and regional

tips for companies looking

to expand into Africa

Anita Gerhardter of

spinal cord research

foundation Wings

for Life

As Russia becomes more

powerful economically,

what opportunities does

this open for its historical

trading partners?

Exceptional July–December 2011

3

Profile: Starbucks

T

Heart

& soul

here’s a “No U-Turn” sign on the

windowsill of Howard Schultz’s

office. A little battered, it stands out

among the coffee memorabilia and

family pictures. It arrived at Starbucks’ Seattle headquarters,

Schultz explains, when he returned as CEO in January 2008

— a gift from his friend Richard Tait, creator of the board

game Cranium. When asked what it means, Schultz smiles

and says: “There’s no going back.”

Schultz’s return after an eight-year hiatus was a bold move

prompted, he asserts, by an emotional attachment to the

company he had built from a small chain of Seattle coffee

retailers into a global empire of 16,000 stores. In 2008,

national economies stood on the brink of collapse and

there were huge internal problems within the company.

As he explains in his recent book, Onward: How Starbucks

Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul, “I could not be

a bystander as Starbucks slipped toward mediocrity.”

The company had been expanding at great speed and

attention to detail was slipping. “We were,” he admits,

With Starbucks, Howard Schultz convinced

millions of consumers that they needed coffee

and a place to hang out. In 2008, he returned to

the helm of the struggling company to remind

us why we fell in love with the brand

words Roshan McArthur_ photography John Keatley/Redux

Exceptional July–December 2011

5

Profile: Starbucks

Starbucks has gone

from one store in

Seattle to 17,000 in

more than 50 countries

“There isn’t anything I would

not do to enhance and preserve

this company”

“measuring and rewarding the wrong thing for a number

of years, which was speed of service transactions and not

quality.” As a result, sales fell fast, along with the stock price.

“The world did not know how bad it was,” he now says.

The process of saving Starbucks required Schultz to

use one of his greatest assets: his tendency to speak

from the heart. “As men,” he suggests, “we are somehow

imprinted or conditioned to be strong, aggressive, macho

and not emotional. And I think that, in a crisis, whether the

cataclysmic financial crisis or a crisis of our own making,

the most important thing to be is authentic.” So, against

the advice of many colleagues, he spoke frankly to his

employees. In an emotional speech to almost 10,000 store

managers and company leaders in New Orleans at the height

of the economic crisis in October 2008, he talked about love.

“It’s not a word you would expect, either from a man or in

the context of a business environment,” he explains. “I said,

I’ve been asked why I came back as CEO. I came back because

of love, how much I love the company, how deeply I feel about

the responsibility we have to the 200,000 people and their

families who are relying on us as leaders. There isn’t anything

I would not do to enhance and preserve this company. Other

than my family, there is nothing I love more than Starbucks.

“I think it is incumbent upon leaders,” he continues, “to

understand that the responsibility and burden of proof is on

themselves to create trust, sensibility, a sense of purpose

and a shared commitment. I don’t think that 20 years ago I

would have had the self-awareness, or the sense of myself,

to be able to unveil that because I was too insecure.”

This was a situation that called for discipline and process —

as well as perspective. “Growth and success have a tendency

to cover up mistakes,” he explains, “and most entrepreneurs

are always looking forward and never in the rearview mirror.

You never go back and look at what you did wrong, because

there’s so much opportunity and the wind is at your back.

That’s a great time in a company, but it’s not sustainable.”

decisions, such as closing every store in the

US for retraining one evening in February

2008. But it also meant sitting in long

meetings, going through the operational

side of the business with a fine-toothed

comb and asking painful questions. It

meant making tough decisions, closing

stores and losing employees, including replacing the majority

of his top executives. “The key issue,” he says, “was finding

people with like-minded values.”

Ultimately, he believes the main reason for the turnaround

in Starbucks’ fortunes was the resiliency of values in the

Back in charge

It is also unusual for someone who

grew a business from its earliest days

to go on to manage his or her company

through all phases of its evolution,

especially in a turnaround situation.

Creating a brand demands one skill set,

but returning to right a wayward ship

is something founders are not known

for. Yet, there have been exceptions,

such as Steve Jobs of Apple and

businessman Charles Schwab.

For Schultz, returning to lead the

company meant using his ingenuity

as an entrepreneur to make maverick

Forty years of Starbucks

Starbucks opens

its first store in

Seattle’s Pike

Place Market

Schultz convinces Starbucks’ founders to

test the coffeehouse concept in downtown

Seattle and the first Starbucks Caffè

Latte is served

Il Giomale acquires Starbucks’

assets and changes its name

to Starbucks Corporation

1971 1982 1984 1985 1987

Howard Schultz joins Starbucks as

director of retail operations and

marketing. Starbucks begins providing

coffee to fine restaurants and espresso bars

Schultz founds Il Giomale, offering

brewed coffee and espresso beverages

made from Starbucks coffee beans

Starbucks is the first privately owned US

company to offer a stock option program

that includes part-time employees

Establishes the Starbucks

Foundation, benefiting local

literacy programs

Acquires Seattle

Coffee Company

1991 1995 1997 1999 2003

Total stores

116

Begins serving Frappuccino

and Starbucks ice cream

Partners with Conservation

International to promote sustainable

coffee-growing practices

Total stores

7,225

Total stores

677

6

Exceptional July–December 2011

7

Profile: Starbucks

“This circle of doing the right

thing for your people and your

customers will ultimately

produce more profit”

Starbucks’ new

logo, which it

has unveiled

for its 40th

anniversary

company and its guiding principles.

“We had always intended to create a

balance between profitability and social

conscience,” he says, “and underneath

that I recognized, especially in the past

couple of years, that success is best when it’s shared.”

These are issues Schultz is passionate about, resulting,

at least in part, from an upbringing in which his parents

taught him “what it means to do the right thing.” Onward

is loaded with references to community, humanity, social

consciousness, responsibility and personal connection, as

well as respect, loyalty, trust and honesty. Community, in

fact, is what he sees as Starbucks’ backbone.

“In terms of our society and the way technology has

evolved, I think there is a growing appetite for human

connection,” he explains.

“I think we’ve been able

to provide the physical

environment and bring

people together.”

Traveling the world over

to visit his stores, Schultz

says: “The Starbucks

experience is as relevant

in Kuwait as it is in Seattle

or Dallas because,

universally, we all have this

desire for human contact.”

This sense of community

Opens first Farmer

Support Center in

San Jose, Costa Rica

also means that he must share his success with his people,

all of whom are called “partners.” In spite of calls from at

least one investor to cut employees’ health care benefits,

he flatly refuses. “The essence and fabric of the company is

linked to those benefits,” he told us. “We would completely

fracture every aspect of the culture we have, which is the

only competitive edge we have.”

More to be done

Financially measured, Schultz has been as successful as a

turnaround CEO as he was as the architect of the Starbucks

phenomenon. But he is quick to say there’s still much to be

done. “We’re as good as we’ve ever been,” he says, “but not

as good as we need to be. There’s no victory lap, there’s no

celebration. If there’s anything we’ve learned from the past

few years, it’s that the hubris and the feeling of invincibility

was a virus at Starbucks. We can’t allow that to ever enter

the building, enter the halls, enter the fabric of the company.

“I’m not good at celebrating anyway,” he adds.

According to Schultz, a seismic change is under way in

the business world, brought about by three factors: the

economic downturn, the development of social and visual

media, and an increased consumer interest in business

ethics. With a massive decline in government spending on

Launches Starbucks VIA Ready Brew Coffee.

Opens East Africa Farmer Support Center

in Kigali, Rwanda

2004 2006 2009 2010

Launches the first paper beverage cup

containing post-consumer recycled fiber,

saving more than 75,000 trees each year

8

Free unlimited Wi-Fi via Starbucks

Digital Network in US stores

Viewpoint

social services, he believes that companies

like Starbucks have to lead the way in terms

of social responsibility, finding unique ways

to provide safety nets in their communities

when governments can no longer afford to.

“There are certain constituents who don’t

like to hear that,” explains Schultz, “because

it could mean less profit for them. But this

circle of doing the right thing for your people

and your customers will ultimately produce

more profit. But you have to believe it and

you have to sustain it.

“We’re not a perfect company,” he adds.

“We can’t do all the things we want to do.

We’re going to make some mistakes. But

the lens through which we’re trying to make

decisions and manage the company is the

lens of humanity, and trying to do the right

thing. We’re willing to take the shots if that’s

the price of admission.”

Tribal knowledge

Being the leader of a public company

has lonely moments, says Howard

Schultz. “You are constantly creating

a road map, a vision, an aspirational

path for people, and there are moments

when you also need to talk to someone

yourself, but there are not a lot of

people you can talk to.”

When he does need to talk, he

calls on organizational consultant

Warren Bennis, a friend and mentor

for 30 years, as well as a small group

of entrepreneurs, including computer

magnate Michael Dell, fellow Seattleite

Jim Sinegal of Costco and Les Wexner

of Limited Brands.

“We’re all in the same position, as

entrepreneurs who built companies

from the ground up,” he says. “We each

have a much different level of personal

commitment and emotional connection

to the enterprise than a hired CEO. It’s

tribal knowledge of what it takes to go

down the road less traveled.”

The making of

an entrepreneur

Bryan Pearce, Americas Director, Entrepreneur Of The Year,

Ernst & Young Boston

Entrepreneurs come in many forms.

There’s the accidental entrepreneur

who stumbles upon a great idea, the

intrapreneur who creates his or her

own company from within a larger

one, and the classic founder, an

innovator who finds a whole new way

of doing business.

But what makes a great

entrepreneur? Perhaps the most

significant quality is the ability

to radically transform a business

model or an industry. Successful

entrepreneurs have great vision and

a passion for creation, a focus that

extends well beyond making money.

They also recognize that plans often

change from their original concept.

They know that the world isn’t static

and they adapt as customer needs and

the competitive environment change.

Innovation is

synonymous with

staying power

Entrepreneurs with “staying

power” have the humility to recognize

that, no matter how impressive their

own skill sets, they need people who

can complement those skills. Smart

entrepreneurs are not afraid to hire

people who are more skilled in certain

areas in order to strengthen the

overall company.

A good understanding of finance is

vital. Successful entrepreneurs know

that finding the right sources and

capital structure for each stage of

the business is critical, as is having a

realistic view of how long it will take

to hit a milestone. Often, a technically

savvy or sales-driven entrepreneur

will benefit from a professional CFO

who can help assess what could go

wrong and ensure that the capital

requirements of the company are

well planned.

Just as every person does not

have all the expertise that a company

needs, few companies have the

complete range of skills they need

to be successful. As a result, forging

partnerships, or even acquiring other

businesses, may be necessary to

realize the entrepreneur’s vision

and strategy.

While every decade brings a new

set of challenges to entrepreneurs,

two stand out today. One is the power

of globalization and the associated

demographic changes, such as the

growth of Asia Pacific or the global

middle class. The second is the way in

which social media is affecting “social

commerce.” Good and bad customer

experiences are now shared instantly.

Successful entrepreneurs know how

to leverage these phenomena to help

build enviable customer relationships.

Most importantly, leading

entrepreneurs know there is no

“finish line,” even when they’ve

reached what appears to be the

pinnacle of their markets. Innovation

and reinvention, fueled by customer

insight, are synonymous with

staying power.

More information

For more on our research into the DNA of an entrepreneur, see page 18. For

a copy of this new report, email victoria.howell-richardson@uk.ey.com. To learn

more about any of the Entrepreneur Of The Year programs in the Americas,

please contact Bryan Pearce, Americas Director, Entrepreneur Of The Year, at

bryan.pearce@ey.com. To find an EOY program near you, visit ey.com/eoy

Exceptional July–December 2011

9

A

Agenda

Essential reading: the latest thought leadership publications from Ernst & Young

How we can help you grow your business: events and activities from Ernst & Young

Investing in new

market leaders:

Ernst & Young’s

services for

fast-growing

companies

Ernst & Young’s

growth markets

network advises some

of the world’s most dynamic public and

private companies. Anchored by more than

300 network leaders across 100 countries,

our teams know what it takes to fast track

a business from inspiration to growing

enterprise to market leader.

Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year

For nearly a quarter of a century, our

prestigious Ernst & Young Entrepreneur

Of The Year (EOY) awards program

recognizes the exceptional men and women

who create the products and services

that keep the global economy moving

forward. Awards are given to entrepreneurs

who have demonstrated excellence and

extraordinary success in areas such as

innovation, financial performance and

personal commitment to their businesses

and communities. EOY gives these fastgrowth businesses an opportunity to join an

influential business network, make contacts

and build new relationships. To learn more

about the program, visit ey.com/eoy

Global IPO

trends 2011

Trends in capital

markets activity can

be difficult to predict,

especially in times

of market volatility.

Learn about the latest

IPO market trends

and issues relevant to companies planning

an IPO in Ernst & Young’s seventh annual

report on the global IPO market.

Wealth under

the spotlight

Tax policy and tax

administration

around the world

are experiencing

unprecedented levels

of change, driven

in large part by the

global financial crisis. This report highlights

some of these global changes and the

subsequent impact being felt by high net

worth individuals.

10

Finance forte

This study provides

insight into the future

requirements of the

group CFO position

and the skills and

capabilities needed

by those in the role,

as well as those who

aspire to the role. It is based on a survey of

more than 530 group CFOs and their direct

reports from across Europe, the Middle

East, India and Africa, as well as a plethora

of in-depth interviews with leading CFOs

and future finance leaders. Please note

that an executive summary for high-growth

companies is available on request.

Competing for

growth: how

business is crossing

boundaries to

succeed

This research seeks to

test and build on the

findings of our first

Competing for growth

report, which showed that high-performing

companies are focused on four drivers

of competitive success: customer reach,

operational agility, cost competitiveness

and stakeholder confidence.

Next-generation

innovation policy

This report

demonstrates that

innovation policy

around the world is

becoming increasingly

complex, and such

complexity is even

more visible in a multi-level government

framework such as the European Union.

An analysis of the emerging trends in

markets and industries shows that a

well-conceived innovation strategy must

use a broader set of tools.

Comparing global

stock exchanges

Business operations

and capital flows are

becoming increasingly

globalized as new

centers of economic

strength and

innovation develop

around the world. Future market-leading

companies are springing up in places such

as China, India and Eastern Europe, in

addition to the mature economies of the US

and Western Europe. While the majority of

companies choose to list on their domestic

stock exchange, business leaders are

increasingly considering accessing public

capital in a foreign market. This report is

designed to be an objective, fact-based

comparative tool for business leaders

weighing up exchange alternatives.

Exceptional goes digital

Want to be able to enjoy the latest

edition of Exceptional on the move?

Now you can. The January–June 2011

edition is ready and available at ey.com

(under the Services/Strategic Growth

Markets section). You will also

soon be able to download it from

EY Insights on your iPad, iPhone or

Android device, through our new

global thought leadership application

(coming soon).

Ernst & Young Entrepreneur

Of The Year Forum 2011

The Ernst & Young Entrepreneur Of The Year

Forum gives EOY alumni the opportunity to

meet and network with other outstanding

EOY winners and finalists from across EMEIA

(Europe, Middle East, India, Africa). The

2011 event took place in Dubai in the Middle

East and focused on exploring new horizons:

new ideas, new markets, new sources of

finance and new technologies.

To learn more about the event, visit

eoy-forum.com

Initial public offerings (IPO)

Ernst & Young has guided thousands of

companies on the journey from start-up

to listed company to major market leader.

While we thrive on helping companies to

deliver successful IPOs, we also recognize

that an IPO is not right for everyone. That’s

why we help you to evaluate the pros and

cons of an IPO, demystify the process,

examine the alternatives and prepare you

for life in the public spotlight. To learn more

about our IPO services, email Penny Cooper

at pcooper2@uk.ey.com

Venture capital and private equity

Ernst & Young’s Venture Capital (VC)

Advisory Group and Private Equity (PE)

teams work with leading VC and PE firms

and their portfolio companies in all global

hotbeds. They offer creative approaches

to issues facing fast-growth companies and

their investors. They provide quarterly and

semi-annual insight, as well as market data

to help VC and PE firms, their partners and

portfolio companies achieve their potential.

Email Tricia O’Shea at toshea@uk.ey.com

Cleantech

As climate change moves up the corporate

agenda, cleantech investment is reaching

record levels. Ernst & Young recently

launched its Global Cleantech Center, which

offers a worldwide team of professionals

who understand the business dynamics

of cleantech. We intend to become the

service provider for emerging cleantech

market leaders around the world and to help

multinational corporations understand the

cleantech landscape and the opportunities

that it brings. For more information on

Ernst & Young’s cleantech capabilities, email

Robert Seiter at robert.seiter@de.ey.com

Family businesses

Family businesses make a significant

contribution to EMEIA’s economies. Our

latest European family business report

concluded that they outstrip non-family

businesses across several key financial

measures. Our research also indicates

that family businesses have a longerterm perspective, flexible and focused

governance, superior talent management and

stronger customer relationships.

Ernst & Young has a history of working

alongside family businesses, providing both

personal and company, as well as domestic

and international, advice and services. For

more information, visit ey.com/familybusiness

Contacts

Ernst & Young has teams throughout the

world dedicated to working alongside

fast-growth businesses. Visit ey.com to

find your local contact, or contact any

of the EMEIA team members below.

Europe

Julie Teigland

+49 621 4208 1151

julie.teigland@de.ey.com

Russia and the CIS

Alexander Ivlev

+7 495 705 9715

alexander.ivlev@ru.ey.com

Middle East

Michael Hasbani

+971 4 312 9141

michael.hasbani@ae.ey.com

India

Farokh Balsara

+91 22 4035 6300

farokh.balsara@in.ey.com

Africa

Zanele Xaba

+27 82 901 0901

zanele.xaba@za.ey.com

Financial Services

Geoffrey Godding

+44 (0)20 7951 1086

ggodding@uk.ey.com

Exceptional July–December 2011

11

Profile: The Co-operative Group

Founded in the 19th

century, the Co-operative

Group’s member-centric

model has stood it in

good stead during the

downturn. Group CEO

Peter Marks explains his

vision for this growing

British business

words Kath Mortimer_ pictures Images courtesy of Cooperative Group

Streets ahead

Manchester’s

Corporation Street in

the 1950s. The building

in the foreground is

the headquarters

of CWS – now the

Co‑operative Group

12

Exceptional July–December 2011

13

Profile: The Co-operative Group

The Co‑operative

grows some of the food

it sells in its shops,

which will be run from

its new 20‑acre site in

Manchester (below)

“I said about five years

ago that we needed

to change or face going

out of business. And

we did change”

P

eter Marks, Group CEO of the Co-operative Group, is a fan

of soccer analogies. “To use one in relation to my career, I’d

say that I’ve played in the second and third division for most

of it,” he says. “But I’ve always wanted to play in the Premier

League. Now we’re back in it.”

Back in it he most definitely is. The Co-operative Group,

based in Manchester, England, currently boasts an annual

turnover of £14b (US$23b), employs 114,000 staff and

operates more than 5,000 retail trading outlets that serve

more than 20 million customers a week. With core interests

in food, financial services, travel, pharmacy, funerals and

farms, the group is one of the few businesses that have

flourished in the credit crunch and come out fighting.

But it has not always been this way. The consumer-owned

Co-operative Movement has, in the past, been fragmented

14

Exceptional July–December 2011

and uncompetitive. Market share in its food retailing

business, historically the Co-operative’s strongest division,

hit a low of 4% at one point. This was a dramatic decline from

the Movement’s halcyon days of the 1970s when one in four

people in the UK shopped in Co-operative stores.

“They called it the Co-operative Movement,” says Marks,

“but it didn’t cooperate and it didn’t move much. Bigger

competitors ate us alive. The likes of Sainsbury’s and Tesco

consolidated and grew, but we stayed where we were. And

we got eaten alive.” He recognized that something needed

to be done. “I was one of the people who said about five

years ago that we needed to change or face going out of

business. And we did change.”

Company man

When Marks speaks, people listen. Indeed, there are few

better placed to comment on the Co-operative’s fortunes

than he is; he joined as a shelf stacker at the age of 17 and

has been with the business ever since. “I have never had

to move to satisfy my career ambitions,” he says. “I have

been fortunate in that the Co-op has given me the business

education, training and opportunities to further my career.”

The Co-operative has always invested heavily in its

employees and in the wider community. Its strong social

conscience has its roots in the Movement’s formation

in 1844, when a group

of 28 workers, tired of

seeing families, friends and

neighbors exploited at work,

decided to form a new kind of

business, and the consumer

cooperative was born.

Unlike other businesses,

it is owned not by a small

group of shareholders, but

by its customers. “We have

six million members at the

moment,” reveals Marks,

“and we hope to make that

20 million, which is a third of

the population of the UK. Why wouldn’t people want to join

the Co-operative? It’s a great organization to be a member

of and you also get a dividend on what you buy.”

Members have to invest only £1. “That’s how cheap it is,”

says Marks. “And for that, eventually and if they were so

inclined, members could join our board of directors and give

me a hard time every month.”

The Co-operative’s membership is at the heart of its

operations and is just one way in which the organization

differs from a public limited company. “The PLC model is

15

Profile: The Co-operative Group

Co-operative by numbers

3,000

360

53b

800

2002

250

The number of its food stores

and supermarkets

“We are very concerned about

the planet we are working on.

I suppose it sounds pompous in

a way, but it is absolutely true”

The number of its travel agencies,

serving three million people a year

How many prescriptions its pharmacies

dispense each year

The number of its funeral homes

The year in which Co-operative Financial

Services was founded

How many Co-operative Bank branches

are on Britain’s high streets

An illustration of the

planned Co-operative

Group headquarters

in Manchester, due

to open in 2012

16

Exceptional July–December 2011

designed for one thing and one thing only: shareholder

value,” says Marks. “If you buy shares in a PLC, you just want

it to make your shareholding more valuable and that’s what

drives boards of directors in the PLC world.”

It is not what drives Marks. For him, a successful business

is about looking after all three groups of stakeholders: its

shareholders — or, in the Co-operative’s case, its members —

its employees and the communities in which it operates.

A social purpose is also a key component of Marks’

definition of a successful

business. “I don’t just mean

box ticking and providing

fancy, glossy CSR reports;

I’m talking about real social

responsibility — putting

things back into society,”

he asserts. This is where

profit comes in. “Profit

is the lifeblood of any

business. If we concerned

ourselves solely with ethics

and values and principles,

then we would be the most

ethical organization in

the corporate graveyard.

But if you are making a

profit, then you have the

ability to do other things

that you think are socially

responsible — what we call

social goals.

“We think long term. We

are very concerned about

the planet we are working

on. I suppose it sounds pompous in a way,

but it is absolutely true.”

There are two events that contributed

most directly to the turnaround in the

Co‑operative’s fortunes. The first came in

2007 when the Co-operative Group merged

with United Co-operatives. Marks describes

this as “transformational.” It delivered about

£70m (US$114m) of extra profit from

the business synergies of that merger in

year one and gave the group the capital for

much-needed investment in its retail stores.

Further growth

The second event was the 2008 acquisition

of the Somerfield chain and its integration

into the Co-operative’s food retail arm.

Within 12 months, the Britannia Building

Society had also been merged into the

Co-operative’s financial services arm, which

includes the Co-operative Bank and Smile,

the internet bank. “In this world, and in the

markets within which we operate, scale is

of crucial importance,” explains Marks. “We

were subscale in both our banking and food

businesses and we had to put that right.”

The Somerfield deal was a particular

coup, coming as it did at the height of the

credit crunch. “We had to go to the City [of

London] to raise £2.5b (US$4b): £1.6b

(US$2.6b) to buy Somerfield, and the

rest to refinance the business,” he says.

“It was quite an undertaking when the banks

were shutting up shop and not lending any

money. But we never considered not doing

it. We knew it was the right thing to do. And

the fact that we did raise that money in

those circumstances is testament to what

a good deal it was.”

So where next for the Co-operative?

Marks refuses to rule anything out. “We

haven’t got any specific plans to open any

retail food stores outside of the UK; we’ve

got plenty to do here at the moment,” Marks

says. “But we do have relationships with

other co‑operatives internationally and we

do talk to them from time to time about

possible tie-ups, so never say never.

“There are two ways a business can go:

forward or backward. We intend to keep the

momentum going and we are going to carry

on working hard in all of the things we do.”

By this time next year, Marks and co. just

might be in the Champions League.

Viewpoint

Growth options for

private companies

Simon Allport,

Senior Leader, North West, UK, Ernst & Young

There comes a point in every

company’s development when

difficult decisions have to be made.

Regardless of the size of operations,

the nature of the industry or the

extent of a company’s ultimate

ambition, such choices represent a

defining moment in an organization’s

history and will prove central to its

future success. The corner shop

owner pondering whether to take on

an extra member of staff; the SME

CEO presented with the possible

takeover of a rival; the multinational

considering launching operations

in a new jurisdiction — all of these

are examples of businesses at a

crossroads, united by the uncertainty

of which way to go next.

The good news for

private companies

looking to expand

is that there are

many opportunities

for growth

The good news for private

companies looking to expand is

that there are generally numerous

opportunities for growth. The

difficulty is in deciding which to take;

the best choice is almost always to

follow multiple paths simultaneously.

The key for private companies is to

have a clear strategic plan for their

future business development.

Inevitably, growth means access

to fresh capital. However, the banks

may not always have the appetite

to provide the levels required, as

most decisions are based on the risk

profile of a business — especially

in the current climate. Margins are

still tight in the lending market,

so the banks must consider every

application carefully. The full picture

tells a different story, as there is an

increasing number of alternative

funding sources to businesses with

the aspirations to grow.

Alternative funding providers

include institutional investors,

private capital (private placement),

commercial paper, private equity

and capital markets. Private equity

especially has the ability not only to

introduce additional capital through

innovative capital structures but

also to add operational expertise

through industry contacts, external

knowledge and fresh ideas for

growth. Institutional capital also

remains a very active market, with

investors constantly seeking new and

innovative ways to structure.

As the world’s economies move

slowly out of recession, the bottom

line is this: in order to expand

and achieve their full potential,

businesses will require additional

capital. The choices ultimately made

by private companies to grow should

reflect their strategic intent and help

them see, or realize, potential in what

will be a growing market.

More information

Please contact Simon Allport at sallport@uk.ey.com. Managing capital is just one

part of our approach for companies seeking funding: the Ernst & Young Capital

Agenda. To learn more, visit ey.com/transactions or, to request a copy of The

essential guide for fast-growth companies: managing capital or The essential guide

for fast-growth companies: private equity, email susannah.webster@uk.ey.com

17

Analysis: The DNA of the entrepreneur

The

difference

defines us

18

Do successful entrepreneurs share the

same DNA? Based on Ernst & Young

research, leading criminal psychologist

Dr. Thomas Müller is not convinced.

Beyond a shared aptitude for handling

risk and pressure, he believes they are

as individual as the rest of us

D

words Damian Reilly

r. Thomas Müller has made a career

of getting inside the minds of terrible

people. FBI trained, he has spent the

better part of three decades traveling

the world working on some of the

highest-profile criminal cases in modern

history. He was part of the team that

psychoanalyzed serial

killer Ted Bundy in

person and, only a week before he spoke

to Exceptional, he was sitting across a

table from Josef Fritzl, trying

to understand how a man could be

capable of such crimes.

Müller’s abilities are in demand:

governments and police forces around

the world call on him regularly to help

solve cases that have baffled them for

years. But he was happy to accept

Ernst & Young’s invitation to look at recent research into what

sets an entrepreneur apart from the rest of society, and apply

his experiences and expertise to it. He presented his findings

at the EMEIA Entrepreneur Of The Year Forum in Dubai.

“Statistics do not explain human behavior,” he says.

“Human beings are too complex for that.”

Over the course of our conversation, Müller makes clear

his avowed belief that all humans are individuals — that there

is no one-size-fits-all way to understand any group of people,

let alone entrepreneurs. He does, however, believe that there

is one set of circumstances in which entrepreneurs will come

to the fore: in crisis.

“My personal opinion is that a good entrepreneur will

show his or her personality not when the sun is shining and

not when the business is running well,” he says. “They show

their qualities when it is raining. They show their qualities

in a crisis situation. That is the big difference between an

entrepreneur and a traditional CEO or a CFO.”

He adds that three of the successful entrepreneur’s

defining characteristics reveal themselves in crisis: the

ability to withstand pressure beyond the point at which

most people would compromise for the sake of security;

an aptitude for risk; and the ability to adapt quickly to new

circumstances. “It is because the entrepreneur is a little bit

closer to the idea, he is closer to the risk,” he says. “We do

not become wise by always being successful. We become

wise by learning how to solve problems and learning from

situations in which we did not have any success.

“One of the key issues in a crisis situation is the willingness

for development,” he continues. “In a crisis situation, some

“A good entrepreneur will show

his or her personality not when

the business is running well,

but in a crisis situation”

people will just want to get back to how things were before.

They will have a harder time than people who say ‘If we go

one step further, what’s the opportunity to be exploited?’”

In discussion of entrepreneurs, Müller will cite leaders

such as Socrates, Martin Luther King Jr. and Mother Teresa

as people who changed history with what he believes is

the entrepreneurial spirit — that is, that they were unafraid

to work tirelessly toward their objectives, all the while

constantly surmounting the apparently insurmountable.

That said, he is well aware of the pressures of leadership

and believes, too, that entrepreneurs should caution

themselves against the possibility of early burnout. “During

my training at the FBI academy in Quantico in Virginia, we had

a rule: if you were in a leading position — such as guiding a

task force team — for a year or more, you were burned out for

the rest of your life,” he says. “At that time, 17 years ago,

Exceptional July–December 2011

19

Analysis: The DNA of the entrepreneur

as a young police officer I didn’t

understand that law. You have to understand

that a taskforce presides over an outstanding

situation: there is a lot of media attention, a

lot of decisions have to be made, a lot of

personnel changes. There are no weekends,

there are no Sundays, no holidays, no

birthdays. It is always continuing, the

relentless routine, making decisions over and

over again.”

Müller, who worked with FBI task forces

in Canada and throughout Asia and Europe,

uses as an example the last task force with

which he worked. The team comprised 30

married people. By the time the mission was

completed, 28 were divorced. “That is what

In his own words

Managing failure

Dr. Thomas Müller on what sets entrepreneurs apart

In the past four to five years, many institutions have

asked: “Where can I get training to deal with failure?”

We have lost the ability to deal with crisis situations.

If you understand the logistics of a crisis situation,

you can handle it. If you don’t know the rules, then you

can’t. People who suggest a particular course of action

in a crisis situation will be better off than those who don’t

do or say anything. At the 1968 Summer Olympics,

Dick Fosbury created the flop when competing in the

high jump, climbing 22 centimeters higher than his

competitors. Sometimes, you have to create a flop — or

People who are calm in a crisis

know it will come to an end.

It’s about analyzing a situation

and making a decision

something different or unique — to best cope with a

particular scenario or situation.

If you can deal with fear, then you will be successful. If

you didn’t have fear, you wouldn’t bother getting into an

elevator — you’d just jump out of a window. Fear is a part

of our lives. You just have to understand it.

As an entrepreneur, if you know how you react to a

crisis, then you can take control. Honest communication

with people is key to a crisis situation. If a ship captain

tells you about a big storm cloud on the horizon and says

“We’re doing all we can to avoid it,” that’s better than

another who says everything is OK.

Calmness is important. People who are calm in a

crisis know it will come to an end. It’s about analyzing a

situation and making a decision. To train yourself to be

cool, you should think of a fly watching you to see your

reaction when you’re angry. A CEO I worked with would

scream and shout at his employees and then go to his

office and cry like a child. He called me and asked for my

help to address the problem and I taught him the “fly”

technique. He realized how bad he looked and later sent

me a letter thanking me for my help.

It’s not the words you speak but the actions you take

in a crisis that define your character as an entrepreneur.

20

2

9

pressure does,” he says. “One of the biggest

challenges any entrepreneur will ever face

is keeping the balance across the various

aspects of his or her life. It is not easy.”

Müller is very aware that entrepreneurs

are special people — they provide a vital

service to any economy. Because of that,

they are people whom the state should take

care to foster and nurture. But he is insistent

that they are as individual as fingerprints.

“Entrepreneurs are very special people,”

he says. “There are 100 people at this

conference. But look around at them and

you will never see two people wearing the

same shoes and the same glasses. We

are all different.”

15

“One of the biggest challenges any

entrepreneur

will face is keeping the balance

456854

across the various aspects of his or her life”

4

7

300

Crunching the numbers

What Ernst & Young’s DNA of the entrepreneur report uncovered

Earlier this year, Ernst & Young surveyed

more than 700 entrepreneurs to look for

common traits. Here’s an overview:

5. Passing it on: almost three-quarters

of those surveyed said they were involved

in supporting other entrepreneurs.

1. Entrepreneurs start early: more than

50% were in business before the age of

30, and almost 10% before 20.

6. Motivating factors: “Making a

difference” was the most common

response when asked what motivated

them professionally. “Making money”

was the least common.

1076

1

639

5 4130

1000

4

89723

2. Actual work experience: more than half

of surveyed entrepreneurs began their

careers in traditional employment before

going it alone. Most said this period was

vital for gaining experience.

3. Repeat chances: the majority of

respondents said they were serial

entrepreneurs, responsible for launching

at least three companies.

4. Money can hinder: 4 out of 10

respondents said nothing held them back

when it came to starting out, but those

who did face obstacles cited money most

frequently as the chief barrier to progress.

456854

7

The number-one characteristic that

entrepreneurs agree makes a difference

is their passion. This is coupled with

their drive to overcome obstacles —

nearly two-thirds had experienced a

setback in their time as an entrepreneur.

In line with Thomas Müller’s findings,

perhaps it is this attitude to risk and

to failure that sets them apart as

business leaders.

1000

7

To request a copy of the DNA of the

entrepreneur report, please email

victoria.howell-richardson@uk.ey.com

Exceptional July–December 2011

456

21

Profile: Grupo Zed

The game

of his life

Self-proclaimed geek Javier Pérez Dolset

is leading Spanish company Zed to the

forefront of the digital entertainment sector

words Dale Fuchs_ photography Matias Costa/Panos Pictures

“Never lose the passion

for what you do. The

day that it becomes

routine, in this sector,

you’re dead”

22

A

s a child, Javier Pérez Dolset was

a proud video game addict. He

played 1980s classics such as

Laser Blast and Dragster every

chance he got — even if it meant losing sleep.

By age 12, he had set five world records

on his Atari console, a primitive ancestor

of modern game consoles, and even made

headlines in his native Spain when he won a

world Laser Blast championship.

“I’m a total geek,” says Pérez Dolset, now

41, with a boyish grin. But when he was not

blasting flying saucers, this athletic young

Spaniard somehow found time to do his

homework. And that’s not all.

Today, Pérez Dolset does more than play

video games. He controls a digital game and

entertainment empire, Madrid-based Zed,

which has 1,500 employees in 61 countries

and R&D centers on five continents.

Zed is perhaps best known as the parent

company of Pyro Studios, maker of the hit

series Commandos: Behind Enemy Lines,

a World War II strategy game. Designed by

Pérez Dolset’s younger brother, Ignacio, it

sold more than five million copies worldwide.

The company also made headlines with

2009’s Planet 51, a €53m (US$77m)

animated film about little green monsters

living in a picket-fence world similar to

1950s America. The award-winning Englishlanguage film, Spain’s second-biggest box

office smash on record, grossed US$350m

through ticket sales, related games, licenses

and other tie-ins around the world.

But the company is also the world’s leader

in mobile content distribution, with a global

network of 130 wireless operators. It is

currently pointing its joystick in the direction

of social gaming, with new Facebook apps

such as Sports City and TV Studio Boss, a

favorite of Pérez Dolset’s daughter.

Pérez Dolset’s passion for entrepreneurship

grew in parallel with his love for computers.

He started his first business with friends at

age 19 — a desktop publishing service using

1990s software such as QuarkXPress and

Freehand. In those days, he used the profits

to buy sail and surf equipment.

In 1989, he and his brother asked their

father for a loan — “less than €100,000,

completely insufficient” — to start a video

game distribution company. They bought

licenses in the UK for titles such as Tomb

Raider and Titus the Fox and sold them in

Spain. In 1992, they had five staff and sales

of €1m (US$1.45m). Four years later, sales

had climbed to €35m (US$65m).

Exceptional July–December 2011

23

Profile: Grupo Zed

Left: Pérez Dolset

imbues the company

with his personal

passion for gaming.

Below: Figurines from

2009’s animated movie

Planet 51

Viewpoint

The back office’s

pivotal role

Stephane Kherroubi, Financial Accounting Advisory Services Leader,

Ernst & Young EMEIA

“We sold in the mornings, we processed

orders in the afternoon and at night we

packaged and sent them,” Pérez Dolset

recalls. “At Christmas time, we worked from

9:00 a.m. to 5:00 a.m. the next day.”

In their scant free time, he and his team

also launched a pioneering internet service

provider, Teleline, which they eventually

sold to Spanish telecommunications giant

Telefónica. The profit became the seed

capital for Pyro Studios and LaNetro, a

leading interactive entertainment portal.

Pyro Studios, which has developed eight

games and sold 10 million copies, was a

dream come true for Ignacio, a movie fanatic

who peppered the Commandos series with

allusions to classic films such as The Dirty

Dozen. “He watches about two or three films

a day,” Pérez Dolset says.

Since 2002, Pérez Dolset and his brother

have turned the family business into

a multiplatform giant, acquiring mobile

content pioneer Zed from TeliaSonera in

2004, British competitor Monstermob

in 2006 and UK-based Player X in 2009.

Zed — Pérez-Dolset’s company adopted

the name at the time of the acquisition —

is one of the few cutting-edge technology

firms that have managed to sprout on

Spanish soil. In fact, the country’s low-tech

business culture has posed the greatest

obstacle to the company’s growth.

First, it hampered efforts to obtain

financial backing. “For technology projects,

there aren’t any investors in Spain,” Pérez

Dolset recalls. “We had to look for financing

24

simulation, on his PlayStation. But he remains

a gamer at heart. “To be an entrepreneur is

to be a gamer,” he says in his office at Zed

headquarters in Madrid, where legions of

young, jeans-wearing programmers develop

the latest apps at computer stations decked

with action figures and toys. “It’s a challenge.

You confront new situations every week.

Here, we confront the unknown every day.

I am now pretty good at strategy.”

“We sold in the mornings, processed

orders in the afternoon and at night

we packaged and sent them”

abroad.” Once there, he had to overcome

negative stereotypes. For instance, many

investors were surprised to learn that

an international hit like Commandos was

produced in Spain. “The prejudice still exists

today,” he says. “Today, the name of Spain

isn’t the best calling card, but 10 or 15 years

ago, it was much worse.”

Spain’s technological lag also made hiring

creative staffing more difficult. “There’s a

lot of isolated, self-taught talent in Spain,

but they’re not used to working within a

system,” he says. “You have to train them to

work as a team, to structure the work. We

still look back and say, ’This is a miracle.’”

Now, as CEO and Co-President of Zed,

Pérez Dolset does not have much free

time to practice his latest craze, a race-car

Strategy king

Indeed, Pérez Dolset remains immersed

in strategy — but not the type you might

find in a video game. The sort of strategy

that concerns him is how to thrive in a

technology-driven field that innovates,

evolves and moves as quickly as the click of

a mouse. And he is succeeding. Despite the

economic crisis, Zed grew by 26% in 2010.

This year, growth has picked up to as much

as 40%. The secret of his staying power?

“Never lose the illusion or passion for what

you do,” he says. “The day that it becomes

routine, in this sector, you’re dead.”

And so, when he isn’t playing with his

children or practicing his swing on his golf

simulator, Pérez Dolset pores over market

statistics and bets on the future. What does

he see in his crystal ball? Not the exploding

apps market — that’s old news for a strategist

like him. Apps are fine for capturing clients,

he says, but they aren’t huge moneymakers.

In his view, the future belongs to mobile

commerce and marketing. He believes the

industry will really take off in two years’ time

and will eventually be worth trillions. That’s

why Zed has invested tens of millions of euros

in recent years on developing marketing tools

that are “super-targeted in terms of personal

information and geographic location.”

It seems this former Laser Blast champion

isn’t content to live on past glories. His

challenge now is to stay one step ahead in

one of the world’s most dynamic industries.

If you run a high-growth business,

you constantly deal with many

urgent matters, such as hiring new

staff, conquering new markets or

streamlining the corporate culture

of new acquisitions. But as you race

forward at a dizzying pace, it is

important to look over your shoulder

at the back office.

Some firms are so intent on

developing their businesses that they

fail to establish secure and efficient

accounting and finance practices.

They think those dull bookkeeping

or finance issues are secondary

to increasing turnover. And then,

months or years later, they discover

that key accounting or finance

topics have been missed or not well

A sound back-office

function will help

you deal with

external issues

managed — but they were too busy to

notice. You can avoid an unpleasant

surprise by attending to those backoffice issues. They form the backbone

of long-term growth. They are what

give you staying power.

A streamlined accounting and

finance system can help you make

decisions, anticipate changes and

prevent problems more easily —

especially if you are dealing with

a complex group of companies

operating in multiple sectors around

the globe. Can you rely on your

accounting and finance data? How

do you evaluate and benchmark the

performance of your teams in India or

Brazil? How do you know if your R&D

in other far-flung outposts is yielding

the right results?

The first step is to homogenize and

align your information systems for

all segments of your company. Then

you must track the right indicators —

profitability, gross margin, cash flow,

working capital — and calibrate them

regularly. You can then compare the

results with home-office standards

in time to make decisions that will

ensure your future growth. With

the leading accounting and finance

practices in place, it’s also easier

to detect problems early on and

challenge local management.

A sound back-office function will

also help with external issues, such

as the multiple tax requirements

and regulations around the world.

This can avoid, for instance,

reassessments and payouts. Strict

compliance is also important in all

communications with local regulatory

agencies and demanding investors.

While expanding your operations,

it’s right to rely on a secure, aligned

system that keeps you up to date on

regulatory and legal changes both at

home and abroad. These measures

might not be as exciting as a new

acquisition, but they will keep the

engine of growth going.

More information

For more information on IFRS conversions, IPOs, transactions, due diligence,

remediation services and services to support financial executives in

implementing new standards and improving their financial communication,

please contact Stephane Kherroubi at stephane.kherroubi@fr.ey.com (EMEIA)

or Ken Marshall, Financial Accounting and Advisory Services Leader,

at kenneth.marshall@ey.com (Americas).

Exceptional July–December 2011

25

Profile: Execution Noble

“There wasn’t an institution

of our size that did more to

reinvent itself over the past

two years than we did”

The view

from here

Nick Finegold’s

entrepreneurial

approach has taken

brokerage firm

Execution Noble far.

Now, its partnership

with a Portuguese

investment bank is

opening up further

opportunities

words James Gavin_ photography Elke Meitzel

Nick Finegold (left)

chats with colleagues

near the firm’s

Paternoster Square

offices in London

26

Exceptional July–December 2011

B

efore Portuguese investment bank Banco Espirito

Santo de Investimento (BESI) acquired a 50.1%

stake in Finegold’s securities firm Execution Noble

in December 2010, brokerage clients would find

themselves shooting pool in the bar of the firm’s office in the

Truman Brewery building in London’s über-cool Brick Lane.

Now ensconced in his second-floor office in the London

Stock Exchange’s Paternoster Square HQ, Finegold appears

comfortable in his surroundings in the heart of London’s

financial services establishment. Yet the 46-year-old founder

and chairman of Execution Noble boasts a résumé that

is closer to buccaneering entrepreneurs such as Richard

Branson than the pin-striped investment bankers he might

mingle with in the corridors.

Shifting to the sober corporate environment of BESI’s

Paternoster Square offices was no big deal when the time

came, says Finegold. “The old office was a huge area of

competitive advantage when we were very small, but when

we got to a certain size and our pool-playing days were over,

it was easier to do business here — and that’s, after all, really

what we care about.”

BESI’s decision to buy into Execution Noble — a rare recent

deal in the UK brokerage space — speaks volumes about

Finegold’s single-minded vision. The former head of equity

sales at Deutsche Bank had determined early on that he

27

Profile: Execution Noble

Teaming up with

BESI has given Nick

Finegold and Execution

Noble many more

opportunities

Simple, says Finegold: by moving into higher

margin markets — the developing markets

and corporate and advisory services. “I don’t

believe there was an institution of our size

that did more to reinvent itself over the past

two years than we did,” he says. “We sold

asset management, bought Noble, and then

we did the third leg with Espirito so that

we are not entrenched in a UK/European

mature equity market. We leverage off our

core competence rather than rely on it.”

“As a result of this deal, we are

in the markets of today and the

markets of tomorrow”

would set out on his own by his mid-30s, and 10 years

ago established Execution as a pure agency brokerage

servicing large institutional clients.

“Basically, we helped champion the cause of nonproprietary environments,” says Finegold. “We highlighted it

as an issue more than a decade ago and it is again relevant

within the context of today’s City [of London].”

Over time, Finegold broadened Execution’s focus, hiring

a research team, developing a bond-trading capability and

acquiring Noble, a Scottish mid- and small-cap specialist

investment bank. Under his watch, Execution mutated into

an integrated securities, capital markets and advisory firm,

competing with the world’s biggest and most profitable

multinational investment banks.

The decision to team up with BESI reflects the stark

changes wrought by the financial crisis. “If you run your

business prudently and save for a rainy day, and then at the

precise point your competition is brought to its knees, bailed

out and then comes knocking on your door to hire your staff,

it quickly sinks in that life’s not fair,” says Finegold. “You can

28

Exceptional July–December 2011

either complain about it or change things

— or as we think, create competition rather

than complain about it.”

BESI’s investment banking franchise allows

Execution Noble to offer a wider range of

equity and fixed-income products through its distribution

platforms. Finegold points to a cultural and strategic fit

between the two groups: both are entrepreneurial and both

evolved from client-focused cultures.

“What’s fascinating about the strength of the Portuguese

culture is that they just go out and get it,” he says. “They are

everywhere, from Macao to Mozambique to India, and that

entrepreneurial spirit permeates this organization.”

With BESI’s backing, Execution will be able to service

clients in some of the world’s most exciting emerging

economies. Part of the logic for doing the deal was to make

the local businesses relevant globally, and to build on its

existing strengths in large- and mid-cap UK and European

stocks. “As a result of this deal, we are in the markets

of today and markets of tomorrow,” says Finegold. “For

example, we now have 200 men on the ground in Brazil.”

The European large- to mid-cap space has been through

difficult times and is burdened with structural overcapacity.

How can Execution prosper against this gloomy backdrop?

Global footprint

The initial growth under BESI’s ownership

will come from linking Brazilian businesses

with customers in London, New York and

Hong Kong. “There are some simple,

quick-win things,” says Finegold. “It is

about monetizing the geographic spread

of interesting businesses and product lines

that we have.”

As Execution Noble builds a global

footprint with its Portuguese partner,

Finegold will continue to focus on the

essentials that helped him build a successful

investment bank from scratch. Self-effacing

to the last — making light of a degree in

textiles and a false start in his first job at

research and consulting provider Wood

Mackenzie — Finegold stakes his business

success on credibility. Dictum meum pactum

(“My word is my bond”) is at the core of his

investment philosophy.

“In our business, you have to like people

and have an interest in people, and that

is what the best salesmen do,” he says.

“They understand that they aren’t just

selling stocks and shares; they are selling

credibility. It’s all about their ability to be

believed above the competition. And very

often you do that not by telling people what

you’re good at, but by telling people what

you're not so good at.”

Whether it is operating out of Brick Lane

or Paternoster Square, credibility remains

the key to Execution’s success story.

Viewpoint

Preparing

for exit

Gavin Jordan, Financial Services Transaction Advisory Services,

Ernst & Young

To ensure maximum value from a

sale, there’s no escaping the need for

rigorous planning. At the very least,

this means a three-month process

from the point at which you press

“go.” But leading practice suggests

the management team should have

been thinking about it for at least a

year before that. It takes that long

to ensure that you can present the

business in its best light.

Everything has to be demonstrable:

a robust business plan, a track

record of past performance — with

up-to-date financial and operational

information and a consistent set

of KPIs — and a clear strategy and

growth opportunities. To get a good

multiple, it’s crucial to prove that the

Focus on planning

to generate the

highest returns

business hasn’t peaked. It can’t look

like you’ve taken the first steps to a

new market just to make the business

look more appealing for a sale.

In fact, such desperate tactics

won’t get you far at all. The

management team needs to be

honest with themselves and realistic

with potential buyers, communicating

exposures clearly and up front.

People don’t like being hit with

unexpected surprises. Business

fundamentals are what generate

a sustainable profit level — and

that’s what bidders will price off.

The multiple will depend on future

strategy and growth opportunities,

and any competitive tension created

by the bidders can add value on top.

Yet even a well-prepared team

will waste all that effort if they get

the timing wrong. This depends not

just on the health of company itself,

but on macro conditions, too. The

general economic situation will affect

the company’s ability to raise debt,

for example, and industry-specific

factors such as impending regulation

can often lead to uncertainty.

At these times, it’s crucial you

ask questions such as: is the market

saying this is the right time to do it?

If yes, have all exit strategies and

buyers’ needs been identified and

thoroughly explored? What processes

will be used to make it happen? What

support will they need to hit the

timetable and get required sign-offs?

What different structural choices do

you have to effect the disposal? Is

the business currently in the best

condition for such a move?

This may all seem like a lot to

consider — but it’s worth it. Our

research has found that management

teams that put a significant focus

on planning for an exit generate the

highest returns. It’s about gathering

all the data that buyers will require,

giving yourself time to correct things,

and going to market with historical

information and a strong future

business plan that is robust and

will stand up to the scrutiny of

potential bidders.

More information

To learn more about preparing for exit strategies and other aspects of growing

your business, contact Gavin Jordan, a specialist in the financial services industry,

at gjordan@uk.ey.com. Alternatively, contact one of our Transaction Advisory