identifying and dealing with taxation issues

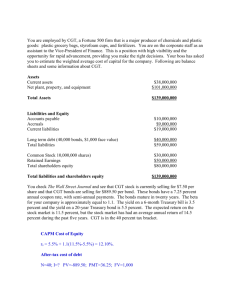

advertisement