Presentation - University of Mississippi

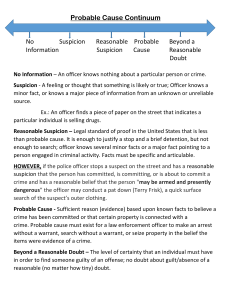

advertisement