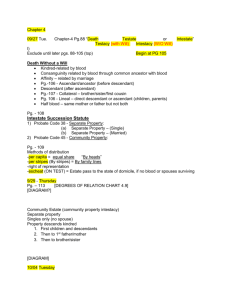

the changing patterns of total intestacy distribution between spouses

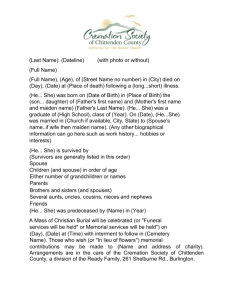

advertisement