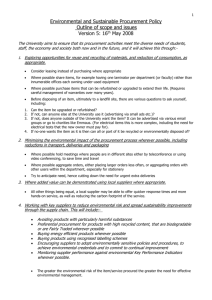

Purchasing Policy and Procedures

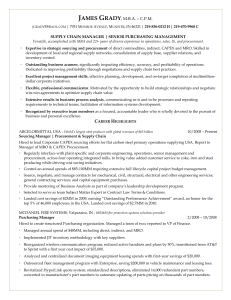

advertisement