839 KB - Competition Policy Review

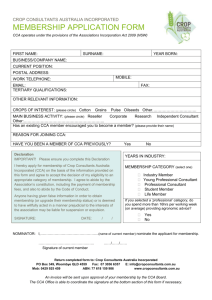

advertisement