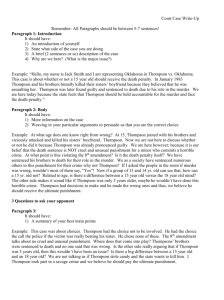

Constructing Text-Based Arguments About Social Issues

advertisement