1995-CA-001057 - Kentucky Supreme Court Opinions

advertisement

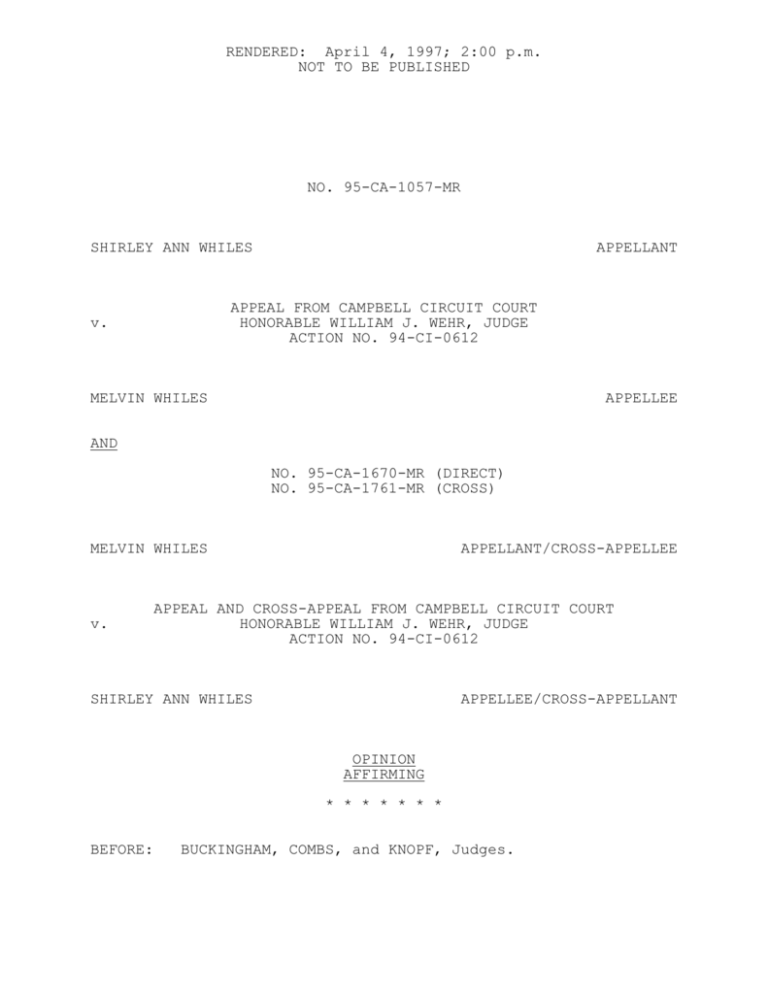

RENDERED: April 4, 1997; 2:00 p.m. NOT TO BE PUBLISHED NO. 95-CA-1057-MR SHIRLEY ANN WHILES APPELLANT APPEAL FROM CAMPBELL CIRCUIT COURT HONORABLE WILLIAM J. WEHR, JUDGE ACTION NO. 94-CI-0612 v. MELVIN WHILES APPELLEE AND NO. 95-CA-1670-MR (DIRECT) NO. 95-CA-1761-MR (CROSS) MELVIN WHILES v. APPELLANT/CROSS-APPELLEE APPEAL AND CROSS-APPEAL FROM CAMPBELL CIRCUIT COURT HONORABLE WILLIAM J. WEHR, JUDGE ACTION NO. 94-CI-0612 SHIRLEY ANN WHILES APPELLEE/CROSS-APPELLANT OPINION AFFIRMING * * * * * * * BEFORE: BUCKINGHAM, COMBS, and KNOPF, Judges. KNOPF, JUDGE: This appeal has a long and complicated history. It began in an unrelated dissolution of marriage action between the appellee/cross-appellant Shirley Ann Whiles and Thomas Whiles (not a party to this action). During that action, Shirley and Thomas brought a third party complaint against Thomas's parents, Melvin and Marie Whiles. They contended that Melvin and Marie orally agreed to sell to them certain real property located in Campbell County, Kentucky. contract. They sought a judgment enforcing the Melvin and Marie took the position that no enforceable land sale contract existed, and that Shirley and Thomas were merely tenants-at-will on the property. After the master commissioner's hearing in that action, but prior to the entry of the master commissioner's report, Melvin filed a forcible detainer complaint against Shirley in Campbell District Court. Upon being advised of the pending circuit court matter, the district court promptly dismissed the eviction action. Shortly thereafter, the master commissioner issued his report, finding that an enforceable land sale contract existed. The trial court subsequently confirmed the master commissioner's report and ordered Melvin and Marie to convey the property to Shirley and Thomas.1 Ultimately, Shirley received the property as part of the settlement in the dissolution action. 1 This court ruled on one issue involving the same parties and property in a previous appeal. Melvin and Marie Whiles v. Shirley and Thomas Richard Whiles, No. 94-CA-2175 (May 10, 1996). The issue of the enforceability of the land sale contract was not appealed. -2- Shirley then brought a complaint against Melvin, alleging abuse of process and malicious prosecution in the filing of the forcible detainer action. Melvin filed a counterclaim seeking reimbursement for taxes and insurance which he had paid on the property and alleging "intentional infliction of emotional distress based upon abuse of process" in bringing her complaint. The trial court granted both Shirley and Melvin's motions for summary judgment. The court found that Shirley's claim of abuse of process failed because she could not establish that Melvin had an improper ulterior purpose in bringing the forcible detainer action. The court rejected her malicious prosecution claim because Melvin established that he brought the eviction action upon advise of counsel, "which is an absolute defense to a malicious prosecution claim." Furthermore, the court found no evidence that Shirley had any damages from the filing of the forcible detainer action. The trial court rejected Melvin's claim for taxes and insurance on the property as barred under the doctrine of res judicata. Finally, the trial court dismissed Melvin's outrageous conduct and abuse of process claim, finding that the alleged conduct did not support a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress. determinations. Both Shirley and Melvin now appeal these Shirley also appealed the trial court's denial of her discovery motion to obtain information about Melvin's assets. We find that the trial court's conclusions are correct, -3- and we affirm. Abuse of process is the irregular or wrongful use of a judicial proceeding. The essential elements of the tort include: (1) an ulterior purpose; and (2) a willful act in the use of process not proper in the regular conduct of the proceeding. Bonnie Braes Farms, Inc. v. Robinson, Ky. App., 598 S.W.2d 765, 766 (1980). The crucial element of abuse of process is that the defendant acted with an improper purpose. Bourbon County Joint Planning Commission v. Simpson, Ky. App., 799 S.W.2d 42, 45 (1990). The gist of the tort is the abuse of otherwise proper judicial process as a means to secure a collateral advantage over another party. Flynn v. Songer, Ky., 399 S.W.2d 491, 495 (1966). The trial court noted that the purpose of the forcible detainer statute is to allow a landowner to evict a party holding possession and to regain possession of the premises. Melvin's goal in bringing the forcible detainer action against Shirley was precisely the same. Shirley contends that Melvin brought the eviction action in an attempt to gain leverage over her in the pending land contract litigation. However, an action for abuse of process will not lie unless the person actually attempts to misuse legal process to gain a collateral advantage over another person which is not proper in the regular course of the proceeding. (1986). Mullins v. Richards, Ky. App., 705 S.W.2d 951, 952 There is no evidence that Melvin ever sought to use the eviction action as a "club" to force Shirley to abandon her claim -4- to the property. Id. at 494. The tort of "malicious prosecution", more properly known as "wrongful use of civil proceedings", is distinct from abuse of process. (1989). Prewitt v. Sexton, Ky. 777 S.W.2d 891, 894 The six (6) elements necessary to establish a claim for wrongful use of civil proceedings are: (1) the institution or continuation of original judicial proceedings; (2) by, or at the instance of the plaintiff; (3) the termination of such proceedings in the defendant's favor; (4) malice in the institution of the proceedings; (5) lack of probable cause for the proceeding; and (6) the suffering of damage as a result. Raine v. Draisin, Ky., 621 S.W.2d 895, 899 (1981). Since the absence of probable cause is an essential element of the tort, the fact that the plaintiff filed the action upon advice of counsel is a complete defense. 872, 873 (1964). Mayes v. Watt, Ky., 387 S.W.2d The advice of counsel need not be sound. Id. All that is necessary is that the plaintiff acted upon advice of counsel after full disclosure of all material facts. Flynn v. Songer, 399 S.W.2d at 494. Melvin presented the affidavit of his prior counsel, Jan Kipp Kreutzer. Ms. Kreutzer stated that she advised Melvin that he could properly bring a forcible detainer complaint against Shirley, on the theory that only a landlord-tenant relationship existed. Significantly, Ms. Kreutzer was also Melvin's trial counsel in the land contract litigation. -5- Melvin established that he brought the forcible detainer complaint upon advice of counsel after full disclosure of all material facts. Shirley presented no evidence to rebut this inference. Under these circumstances, Melvin had probable cause to bring the eviction action. Furthermore, we agree with the trial court that Shirley failed to allege any physical or mental symptoms which were directly related to the eviction proceedings. 621 S.W.2d at 900. Raine v. Draisin, There was no evidence that the proceedings were made public or that her reputation was tarnished. Shirley's lack of appreciable damages, as well as her failure to establish that Melvin brought the action without probable cause, is fatal to her claim for wrongful use of civil proceedings. Since the trial court properly dismissed both of Shirley's claims, her appeal of the discovery issue regarding punitive damages is now moot. Melvin also argues that the trial court improperly dismissed his claim against Shirley for abuse of process. Yet in the action below, he never couched his claim against Shirley as abuse of process. Rather, he characterized his claim as "tort liability for intentional infliction of emotional distress and for the filing of frivolous claims which is in the nature of an abuse of process cause of action." In his memoranda before the trial court, Melvin never argued abuse of process as an independent cause of action, but only as it related to his -6- outrageous conduct claim. He is precluded from raising it for the first time on appeal. The Supreme Court of Kentucky adopted the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress, or "outrage" in Craft v. Rice, Ky., 671 S.W.2d 247 (1984). Craft, and the Restatement (Second) of Torts, § 46, define it as "the intentional or reckless causation of severe emotional distress by outrageous, extreme and intolerable conduct by the defendant upon the plaintiff." Liability is found only where the conduct has been so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency and to be regarded as atrocious and utterly intolerable in a civilized community. Restatement (Second) of Torts, § 46, Comment (d). Even gross negligence is insufficient to support a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress. Humana of Kentucky, Inc. v. Seitz, Ky., 796 S.W.2d 1, 4 (1990). The tort of outrage was adopted as a "gap-filler", providing redress for extreme emotional distress in those instances in which the traditional common law did not apply. [W]here an actor's conduct amounts to the commission of one of the traditional torts such as assault, battery, or negligence for which recovery for emotional distress is allowed, and the conduct was not intended only to cause extreme emotional distress in the victim, the tort of outrage will not lie. Recovery for emotional distress in those instances must be had under the appropriate traditional common law action. The tort of outrage was intended to supplement the existing forms of recovery, not swallow them -7- up. Rigazio v. Archdiocese of Louisville, Ky., 853 S.W.2d 295, 299 (1993). The mere act of filing a lawsuit, even a frivolous one, does not reach the level of "outrageousness" necessary to support a cause of action for intentional infliction of emotional distress. If Melvin had a cause of action arising from Shirley's filing of the complaint, he should have pursued it only as an abuse of process claim. The trial court correctly dismissed his claim. Lastly, Melvin contends that the trial court erred in dismissing his claim for taxes and insurance which he paid on the property. CR 13.01 requires that: A pleading shall state as a counterclaim any claim which at the time of serving the pleading the pleader has against any opposing party, if it arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party's claim and does not require for its adjudication the presence of third parties of whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction. The doctrine of res judicata not only bars subsequent litigation of the same subject matter, but it also bars any claim which properly belonged to the subject of the litigation in the first action and which in the exercise of reasonable diligence might have been brought forward at that time. Egbert v. Curtis, Ky. App., 695 S.W.2d 123, 124 (1985). Melvin first argues that his claim for taxes and insurance which he paid on the property did not belong properly -8- in the divorce litigation. However, the Civil Rules remain applicable in a proceeding for dissolution of marriage. KRS 403.130. Shirley and Thomas brought their claim against Melvin and Marie as a third party complaint pursuant to CR 14.01. Melvin was required to assert any counterclaims arising out of the alleged land sale contract at that time. Melvin next argues that he could not have raised his reimbursement claim in the prior action because no actual controversy existed until the court found that an enforceable land sale contract existed. We disagree. He could have asserted the claim alternatively in his answer to Shirley and Thomas's third party complaint, or he could have filed an amended complaint after the trial court entered its order confirming the master commissioner's report. His claim for taxes and insurance on the property clearly arises out of the subject matter of Shirley and Thomas's complaint and it belonged in that action. He is now barred from bringing it now. Accordingly, the judgments of the Campbell Circuit Court are affirmed. ALL CONCUR. -9- BRIEF FOR APPELLANT: BRIEF FOR APPELLEE: Bernard J. Blau Jolly & Blau Cold Spring, Kentucky N. Jeffrey Blankenship Monohan, Hertz & Blankenship Florence, Kentucky -10-