The Relationship Context of Human Behavior and Development

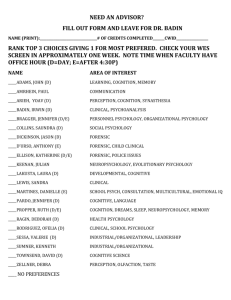

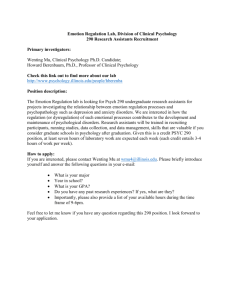

advertisement