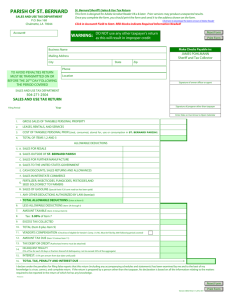

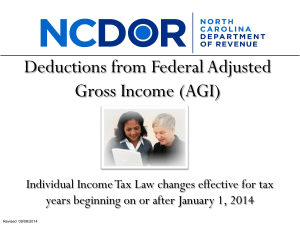

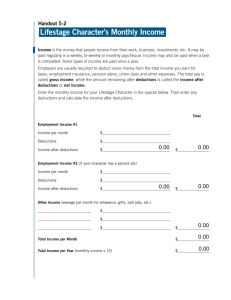

Allowable deductions – essentials

advertisement