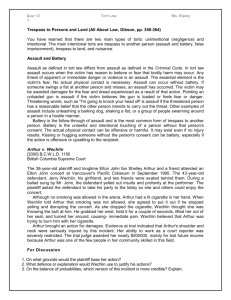

View Article

advertisement