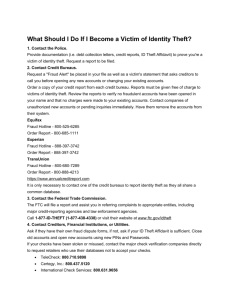

Caselaw on Identity Theft

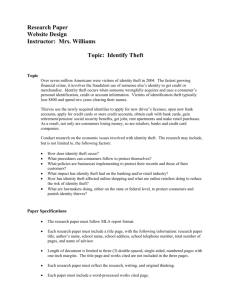

advertisement