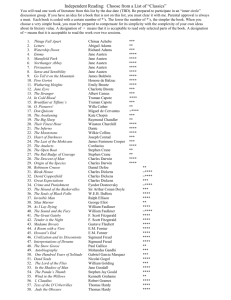

Jane Austen: Emma

advertisement