Anatomy in practice: the ischiorectal fossae

advertisement

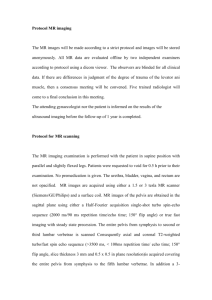

Scholarly Paper: Clinical Perspective Anatomy in practice: the ischiorectal fossae Susan Mercer PhD, FNZCP Senior Lecturer Department of Anatomy & Structural Biology University of Otago. E. Jean Hay-Smith PhD, MNZCP Lecturer Rehabilitation Teaching and Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Wellington School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Otago. ABSTRACT External palpation of the levator ani muscles is based on the premise that these muscles are readily palpable. However, examination of the clinical anatomy of the perineum revealed that the deep, fat filled, ischiorectal fossae lie between the perineal skin and these muscles. The three dimensional anatomy of the perineum is not commonly included in clinical texts. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to present the morphology of the perineum and in particular the ischiorectal fossae and the implications of this morphology for external palpation of the levator ani muscles. Mercer S, Hay-Smith EJ (2005). Anatomy in practice: the ischiorectal fossa. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy 33(2) 61-64. Keywords: palpation, levator ani, perineum INTRODUCTION Increasing numbers of clinicians are interested in the function and dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles. To address dysfunction, clinicians have adapted common assessment and treatment techniques to make them specific to muscles of the pelvic floor. Examples of assessment include perineal, vaginal and rectal palpation, and vaginal and anal surface electromyography, while treatment techniques include pelvic floor muscle training, vaginal and rectal electrical stimulation, and biofeedback. The biological rationale underlying these techniques draws on the topography of the pelvic floor muscles. Levator ani and coccygeus, considered to be the primary supporting and sphincteric muscles of the pelvic floor, are the focus of most anatomical descriptions included in clinical texts concerned with assessment and treatment techniques. Notably, the depictions of these muscles in clinical texts are usually perineal and pelvic views where the associated soft tissues have been removed to reveal the muscles of interest. It is difficult for line drawings to convey the three-dimensional anatomy of the muscles in situ, along with the necessary details of the surrounding soft tissues, including fat, fascia and neurovascular bundles. The problem of using one anatomical description, often only a diagram from a single text, is that clinicians can develop assessment and treatment techniques based on an incomplete understanding of the relevant anatomy. An example of this predicament is illustrated by the ‘pelvic clock exam’, where it is suggested that the levator ani muscle is externally palpable in the anal triangle (Kotarinos, Herman and Wallace, 1997). This assessment NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – July 2005. Vol. 33, 2 technique is based on a perineal approach to the levator ani muscle, with the 4, 5, 7 and 8 o’clock positions representing the levator ani muscles (Figure 1). External palpation is used to assess muscle tone, tenderness or trigger points. Figure 1. A diagram of the ‘Pelvic Clock Exam’, a technique for external palpation of the levator ani (adapted from Kotarinos et al., 1997). Numbers 4, 5, 7 and 8 represent the sites where the levator ani is noted to be readily accessible for external palpation. Review of the ‘pelvic clock exam’ revealed an apparent lack of appreciation of the anatomy of the ischiorectal fossae, which is found between the levator ani muscles and the skin of the perineum. 61 The purpose of this paper is to describe the anatomy of the ischiorectal fossae by presenting the levator ani in situ as they are approached during external palpation. A review of commonly used anatomical texts (Boileau et al 1965; Hall-Craggs 1995; Rosse & Gaddum-Rosse 1997; McMinn 1994; Gardner et al. 1975; Hollinshead 1956; Last 1963; Snell 1995; Woodburne & Burkel,1988) was undertaken and a synopsis of the anatomical descriptions is presented. This is supplemented by images chosen to depict the three dimensional anatomy of the ischiorectal fossae. anal triangles is defined by the posterior edge of the perineal membrane. The external genitalia and the urogenital diaphragm are found within the urogenital triangle, while the anal triangle is composed of the centrally placed anal canal encircled by the external anal sphincter and flanked laterally and posteriorly by the ischiorectal fossae (Figure 3). Perineum Before considering the detailed anatomy of the ischiorectal fossae one needs an appreciation of the regional anatomy, namely the perineum. The perineum is the external aspect of the pelvic outlet from the levator ani muscles through to the perineal skin, external genitalia and openings of the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts. It is a diamond shaped space bounded by the angles formed by the inferior pubic ligament at the pubic symphysis, the tip of the coccyx and the ischial tuberosities. The sides are created by the right and left pubic arch and the sacrotuberous ligaments (Figure 2). The levator ani muscles form a common roof over both triangles. Because these muscles slope down medially the perineum is relatively deep laterally, becoming shallower as it reaches the midline. Figure 3. A photograph of the perineum from below. Posteriorly the coccyx (C) flanked by gluteus maximus (GM). In the midline is the external anal sphincter (EAS) flanked by the perineal membrane (PM). Lateral and posterior to the anal canal are the ischiorectal fossae where the fat has been removed to reveal rectal nerves and vessels. The levator ani (LA) muscles can be seen sloping downwards towards the midline. Figure 2. An inferior view of a model of the pelvis demonstrating the boundaries of the perineum, urogenital and anal triangles. The borders of the perineum are the pubic symphysis (PS), pubic arch (PA), ischial tuberosities (IT), the sacrotuberous ligaments (ST) and the coccyx (C). The line drawn between the ischial tuberosities (IT) represents the posterior edge of the perineal membrane. It is the dividing line between the anterior, urogenital triangle (UT) and the posterior, anal triangle (AT). A line drawn just anterior to the ischial tuberosities divides the perineum into two areas: an anterior region called the urogenital triangle and a posterior region called the anal triangle (Figure 2). The dividing line between the urogenital and 62 Ischiorectal Fossae The ischiorectal fossae are fascia-lined wedge shaped spaces found on either side of the anal canal and rectum. They are potential spaces lying above the skin of the anal region but below the roof of the perineum, which is formed by the levator ani muscles. Although two fossae are described they communicate posteriorly, behind the anal canal. The anatomy of the fossae relates to their primary function as distensible space fillers while also supplying support to the anal canal. In order to provide structural soundness and support to the anal canal, the fossae are filled with fat rather than air. During defaecation the anal canal, now full of faeces, is able to distend into the fossae. When the rectum is empty the shape of the region is maintained and the anal canal is supported. The ischiorectal fat pad also allows for NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – July 2005. Vol. 33, 2 Figure 4. A transverse section through a male pelvis at the level of the pubic symphysis (PS). In the midline lie the bladder (B) and rectum (R). The lateral walls of the fat filled ischiorectal fossa (IF) are formed by the obturator internus (OI) while the medial walls are formed by the iliococcygeus (IC) and puborectalis (PR) portions of the levator ani. The posterior aspect of the fossa are overlaid by the gluteus maximus muscles (GM). dilation of the vagina during parturition when the foetal head virtually eliminates the space. The essentially vertical lateral wall of an ischiorectal fossa is formed by the ischium with its attached obturator internus and associated fascia (Figure 4). The oblique medial wall is formed by the sloping inferior surface of the levator ani as it descends to surround the anal canal (Figure 3). Because the levator ani arises from the fascia overlying the obturator internus the lateral and medial wall meet superiorly at a sharp angle. This angle is usually considered to comprise the roof of the fossa. However, posterior to the anal canal the levator ani is directed towards the anococcygeal raphe and the coccyx, so here the muscle forms a roof to the fossa, not a medial wall. Posteriorly the ischiorectal fossae extends below the lower edge of gluteus maximus as far as the sacrotuberous ligament (Figure 4). Anteriorly it extends forward above the urogenital diaphragm to fill the triangular space between the urogenital diaphragm and the levator ani as they approach each other. Here, the perineal body prevents communication between the right and left fossae. The ischiorectal fossae are filled with adipose tissue that is infiltrated with numerous tough, fibrous bands and septa, some of which are derived from the longitudinal muscle of the anal canal (Figure 4). In fact, Hollinshead (1956) states that this fat is notable for its tough and stringy nature. In the lateral wall of each fossa a pudendal canal for the pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels is located about 4cm superior to the lower border of the ischial tuberosity. The fossae are also NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – July 2005. Vol. 33, 2 crossed by the inferior rectal nerves and vessels. Posteriorly the perineal branch of the fourth sacral nerve and the perforating cutaneous nerve passes through the fossa. Anteriorly the perineal and posterior scrotal or labial branches of the perineal nerve and vessels are found (Figure 3). Implications for External Palpation of the Levator ani Review of the anatomy of the perineum reveals that external palpation of the levator ani muscles must occur through the fat filled ischiorectal fossa (Figures Figure 5. A coronal MRI through a male pelvis at the level of the anus. External palpation of the levator ani muscles (LA) must occur through the fat filled ischiorectal fossa (IF). 63 4 and 5). For example, a coronal Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI) in one living adult male revealed that, at the level of the anal ring, the approximate distance from perineal skin to the mid-point of the levator ani was 10cms (Figure 5). Futhermore, this fat is traversed by numerous tough fibrous bands and septa, nerves and blood vessels. It is conceivable that one could detect levator ani muscle contraction because of its effect on the ischiorectal fat pad. However accurate, graded assessment of levator ani muscle contraction, or an evaluation of muscle tone at rest or during a voluntary contraction, would appear to be extremely difficult. External palpation may provoke pain. However, the source of this pain could be any of the structures which lie between the palpating finger and the levator ani muscle, that is. skin, ischiorectal fat, fascia and neurovascular bundles. Therefore, on the basis of the underlying anatomy, diagnosis of a specific trigger point within the posterior levator ani is questionable. Key Points External palpation of the levator ani musculature is confounded by the overlying fat filled ischiorectal fossae. In order to justify a procedure on the basis of anatomy, a necessary consideration is the anatomy of the structure in situ. 64 REFERENCES Boileau Grant JC and Basmajian JV (1965): Grant’s Method of Anatomy. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, pp. 299-302. Hall-Craggs ECB (1995): Anatomy as a basis for clinical medicine. London: Williams & Wilkins, pp. 334-339. Gardner E, Gray DJ and O’Rahilly R. (1975): Anatomy. A regional study of human structure. London: WB Saunders, pp. 500-501. Hollinshead WH (1956): Anatomy for Surgeons: Volume 2. The Thorax, Abdomen, and Pelvis. Hoeber-Harper, pp 849-852. Kotarinos RK, Herman H, Wallace K (1997): Chapter 3 Assessment. In E Wilder (ed), The Gynecological Manual, American Physical Therapy Association Section on Women’s Health. Alexandria: American Physical Therapy Association, pp 51-89. Last RJ (1963): Anatomy regional and Applied. London: J & A Churchill Ltd. McMinn RMH. (1994): Last’s Anatomy. Regional and applied. London: Churchill Livingstone, pp 404-405. Rosse C and Gaddum-Rosse. (1997): Hollinshead’s Textbook of Anatomy. New York: Lippincott – Raven pp 9. Snell RS (1995): Clinical Anatomy for Medical Students. Boston: Little, Brown and Co, pp 348-355. Woodburne RT and Burkel WE (1988): Essentials of Human Anatomy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp 520-522. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors gratefully acknowledge Mr Brynley Crosado, Mrs Shannon O’Neill and Mr Russell Barnett of the Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, University of Otago, Dunedin for preparation of the anatomical material photographed. Joanna Knox, Anthony Chapman and Fiona Duncan dissected a specimen during a student project under our supervision, and this initial work stimulated our continued interest in the area. ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE Dr Susan Mercer, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072. Australia. NZ Journal of Physiotherapy – July 2005. Vol. 33, 2