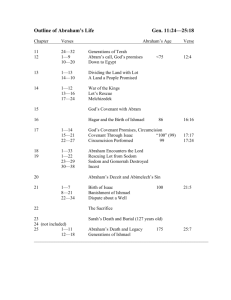

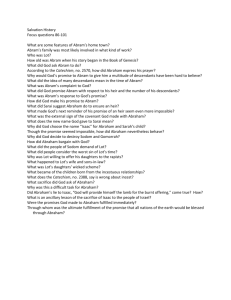

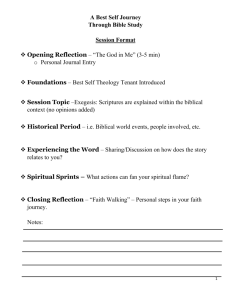

Genesis, Chapter 12, Essays

advertisement