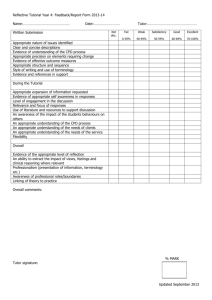

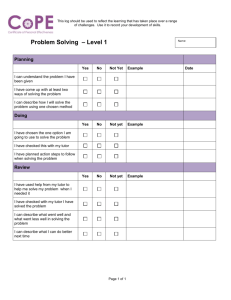

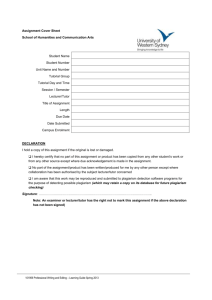

To Problem-Based Learning (PBL) Tutorials In Phase I Curriculum of

advertisement