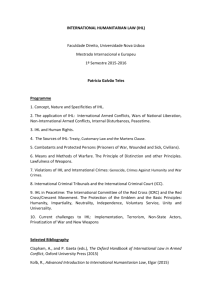

Women Working for Normalization - Women Engaged in Action On

advertisement