Methods to Improve Success with the GlideScope Video

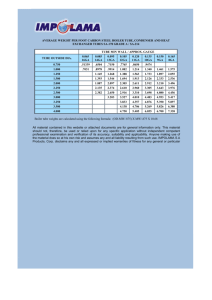

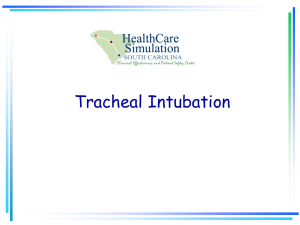

advertisement

Methods to Improve Success With the GlideScope Video Laryngoscope Darrell Nemec, CRNA, DNAP Paul N. Austin, CRNA, PhD Loraine S. Silvestro, PhD Occasionally intubation of patients is difficult using a video laryngoscope (GlideScope, Verathon Medical) because of an inability to guide the endotracheal tube to the glottis or pass the tube into the trachea despite an adequate view of the glottis. We examined methods to improve success when this difficulty occurs. A literature search revealed 253 potential sources, with 25 meeting search criteria: 7 randomized controlled trials, 4 descriptive studies, 8 case series, and 6 case reports. Findings from the randomized controlled trials suggested that using a flexible-tipped endotracheal tube with a rigid stylet (GlideRite, Verathon Medical) improved intubation success, whereas other methods did not, such as using a forceps-guided endotracheal tube exchanger. If a malleable stylet was T he video laryngoscope is used to facilitate endotracheal intubation in cases of a suspected or unanticipated difficult airway.1 The GlideScope video laryngoscope (GSV; Verathon Medical) was introduced in 2001 and provides direct visualization of the larynx in patients with a potentially difficult airway. The GlideRite stylet (GRS; Verathon Medical) is placed into the endotracheal (ET) tube to help direct the ET tube through the glottic opening.2,3 Despite the success of the GSV as an intubation device,4-8 there have been reports of problems, including failure to successfully intubate patients.5 A high-grade Cormack and Lehane9 view due to excessive GSV advancement resulting in the camera being close to the vocal cords can impede directing the ET tube through the glottic opening. Problems due to excessive GSV advancement include little room for the GSV and the ET tube, decreased field of view, and distortion of the anatomy, such as creating a sharp laryngeal angle in relation to the trachea.10 Even when the GSV is not advanced excessively, there can be problems in passing the ET tube into the trachea.5 We examined methods of facilitating the passage of the ET tube into the trachea under these conditions. Materials and Methods •The Clinical Question. The PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) question11 guiding the www.aana.com/aanajournalonline used, a 90° bend above the endotracheal tube cuff was preferable to a 60° bend. Evidence from lower-level sources suggested that several interventions were helpful, including using a controllable stylet, a fiberoptic bronchoscope in conjunction with the GlideScope, or an intubation guide, and twisting the endotracheal tube to facilitate passage into the trachea. Providers must consider the risks and benefits of any technique, particularly if the device manufacturer does not recommend the technique. Further rigorous investigations should be conducted examining methods to increase success. Keywords: Airway, anesthesia, complications, GlideScope, video laryngoscope, video laryngoscopy. search for evidence was as follows: In patients undergoing video laryngoscopy with the GSV where there is adequate visualization of the glottic opening, what additional maneuvers help improve intubation success? •Search Strategy. A search was conducted using the following search engines (2001 to 2014): PubMed, the Cochrane Library, SUMSearch, the GSV operator and service manual from Verathon Medical, and professional and governmental websites. The authors examined the reference lists of obtained sources for other potential sources of evidence. The following keywords and keyword strings were used alone or in combination: difficult intubation, failed intubation, GlideScope video laryngoscope, intubation failures with the GlideScope video laryngoscope, difficult intubation techniques using the GlideScope, Parker Flex-Tip endotracheal tube, GlideScope-assisted fiberoptic intubation, and trauma associated with the use of the GlideScope. The following were the inclusion criteria: systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies, cases series, and case reports involving human subjects published in the English language, in peer-reviewed journals in full-text form or on a professional specialty website addressing the PICO question. Lower-level evidence such as observational studies, case series, and case reports were included because of the nature of the problem. Evidence where a video laryngoscope was used other than the GSV was considered AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 389 because of the similarities between these devices. The evidence was appraised and classified by level according to the method proposed by Melnyk and FineoutOverholt.12 The hierarchy of evidence described in this method ranges from level I (systematic review or metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials) to level VII (expert opinion). Results Two hundred fifty-two sources were found, and after a review of the sources and removal of any duplicates, 25 met the inclusion criteria (Tables 1 and 2).13-37 All the techniques described in Table 2 were reported to be successful. There were 7 RCTs15,17-21,23 with a total of 750 subjects (ranging from 5821 to 19615 per study) and 4 descriptive studies13,14,16,22 totaling more than 1,029 subjects (from 16 to greater than 500 subjects in each study); there also were 8 cases series24-31 (41 subjects, ranging from 429,31 to 1328 per study with the number not specified in 3 articles26,27,30) and 6 case reports.32-37 Five of the RCTs were conducted outside the United States.15,17,18,20,23 All investigators randomly assigned subjects to control or intervention groups,15,17-21,23 and in 2 studies19,21 the authors used a randomized block design to control for potential confounders such as operator experience. There was at least partial blinding of operators and observers in 5 of the studies,15,17,19-21 no blinding in 1 study,23 and the authors of the other RCT18 did not comment on blinding. The sample size in 5 of the studies was determined using a power analysis,15,17,20,21,23 in 1 study the sample size was described as “appeared reasonable”,19 and the other RCT18 did not comment on the method of sample size determination. The subjects in the control and intervention groups overall were comparable.15,17-21,23 All the subjects in 5 RCTs were assessed preoperatively as not being difficult to intubate (normal airway),15,17,18,20,21 and most of the subjects in another study19 were assessed as having a normal airway. A difficult airway was simulated in the final study by placing a semirigid cervical collar on the subject and strapping the subject’s head to the bed.23 Operators were described as experienced,17,19,21 novice,20 and heterogenous,15 but some authors18,23 did not indicate operator experience. All subjects were intubated after induction of general anesthesia and administration of a muscle relaxant.15,17-21,23 Of the 4 descriptive studies,13,14,16,22 most described the respective interventions as being effective.13,14,16 None of the authors discussed blinding, and usually they did not discuss sample size determination13,14,16; however, the authors of 1 study22 performed a power analysis to determine the required sample size. Subject airways were assessed preoperatively as being normal,16 normal and abnormal,13,14 or potentially difficult. Operator’s experience was most often not described.13,14,16 Subjects were 390 AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 intubated after induction of general anesthesia,13,16 or the anesthetic technique was not described.14,22 All but 1 study lacked a control group.22 Of the 8 cases series,24-31 4 reports27-29,31 originated from outside the United States. None of the authors discussed blinding and sample size determination. Subjects’ airways were assessed preoperatively as being normal and abnormal25,26,31 or potentially difficult,28,29 and airway status was not indicated in 3 sources.24,27,30 Operator’s experience was often not described.25,26,28,29 The subjects were intubated after induction of general anesthesia24,26,31 or sedation and administration of topical anesthetic to the airway26,28; in 4 reports, the anesthetic technique was not described.25,27,29,30 The authors of all the case series reported that the interventions were effective, suggesting the possibility of publication bias.24-31 All but 134 of the 6 case reports32-37 were from the United States. Subjects’ airways were assessed preoperatively as normal35 or potentially difficult33,34,36,37 and were not described in 1 source.32 Authors of 5 of the reports33-37 stated they used the described intervention after failure using a standard laryngoscope or GSV or both, and the technique described was successful. Most subjects were intubated after induction of general anesthesia and administration of a muscle relaxant.32,33,35-37 Authors of only 1 study described the operator’s experience.35 Interventions described included using alternatives to the GRS such as an intubation guide,32,37 using a malleable stylet shaped to the GSV blade and rotating the ET tube after passing below the glottic opening,35 GSVassisted fiberoptic bronchoscope intubation (FOBI),33,34 or GSV-assisted FOBI with the ET tube bevel facing posteriorly.36 Discussion •Stronger Evidence. The highest level of evidence was from 7 RCTs.15,17-21,23 Below is a summary of these findings. •Malleable Stylet With 90° Bend Formed 8 cm From the Tip Compared With GlideRite Stylet. Using an ET tube with an acute bend was proposed to improve intubation success by increasing the ability to advance the ET tube through the glottic opening. Authors of 2 studies compared using a malleable stylet with a 90° bend formed 8 cm from the tip with the GRS.17,20 Operators were described as expert17 or novice.20 Authors of these studies17,20 reported a difference between the stylets in outcomes, including time to intubation, ease of intubation, Cormack and Lehane grade view, number of attempts, and number of laryngeal manipulations. Some authors reported that operators voiced more dissatisfaction when using the GRS.17 •Endotracheal Tube With a Malleable Tip Compared With GlideRite Stylet. Investigators of 1 study compared an ET tube with a malleable tip shaped into a “J” with www.aana.com/aanajournalonline the GRS.18 Avoiding the use of the GRS was proposed to lessen the risk of airway injury. The only significant difference reported was the mean time to intubation favoring the GRS by 8 seconds. Intubation was unsuccessful in 2 subjects, who subsequently were intubated using the GRS. This study may have been underpowered. •Endotracheal Tube Forward or Reverse Camber Loaded on Malleable Stylet Compared With 60° or 90° Bend. Investigators of 1 study compared an ET tube loaded (forward or reverse camber; Figures 1 and 2) on a malleable stylet with a 60° bend compared with an ET tube loaded (forward or reverse camber) on a malleable stylet with a 90° bend.15 The reverse camber loading was proposed to overcome the problem of the tip of ET tube hitting the anterior tracheal wall and the 90° bend to facilitate directing the ET tube through the glottic opening. The camber had no impact on time to intubation. The mean time to intubation was significantly less with use of the malleable stylet with a 90° bend (47.1 seconds vs 54.4 seconds). The use of a stylet with a 90° bend also resulted in significantly increased ease of intubation and less use of external laryngeal manipulations. Evidence found incidentally suggested using a jaw thrust, but not laryngeal manipulations such as cricoid pressure, may aid in directing the ET tube through the glottis.38 The other authors19 compared using a reverse camber loaded (they termed it “reverse loaded”) ET tube on a malleable stylet with a 60° or 90° bend. Fifty-one of 60 subjects were successfully intubated using the stylet with 90° bend compared with 51 of 60 subjects successfully intubated using the stylet with 60° bend (odds ratio 10.41, P < .05). All subjects in the 60° bend group were subsequently successfully intubated using a stylet with a 90° bend. They reported a greater ability in reaching the glottic opening using the 90° bend. •Flexible-Tip Compared With Standard Endotracheal Tube (Both Loaded on GlideRite Stylet). Investigators21 compared an ET tube with a flexible tip (Parker FlexTip, Parker Medical) with a conventional ET tube with both loaded on a GRS. This tube improved the ease of intubation during suboptimal conditions, likely because it incorporates a 37° bevel facing posteriorly and its tip has the added flexibility to help it glide over the airway structures (Figure 3). Using a randomized block design to help control for operator experience, the authors reported a shorter mean time to intubation (defined as the time from optimal glottic view via the GSV to the ET tube passing through the glottis) with the flexible-tip ET tube (8.2 vs 14.2 seconds, P < .005). Operators also reported significantly greater ease of intubation with the flexibletip ET tube. The flexible tip may allow the ET tube to better follow the contour of the trachea, especially when the ET tube tip passes through the glottic opening but encounters the anterior tracheal wall. •Endotracheal Tube Exchanger Placed Into Trachea www.aana.com/aanajournalonline With the Aid of Vascular Forceps Compared With GlideRite Stylet. There was no significant difference in intubating the subject on the first attempt or the time to intubation between the groups (stylet- or forceps-guided ET tube exchanger).23 There was a higher incidence of postoperative sore throat with use of the GRS.23 •Weaker Evidence. The evidence from descriptive studies13,14,16,22 or case series24-31 is weaker evidence. Interventions examined included using the GSV in combination with a fiberoptic bronchoscope,16,24,28 the GSV22,25,26 or a similar device14 with a malleable stylet rather than the GRS, a controllable stylet,27 or the GSV with an intubation guide rather than the GRS.13,29-31 Case reports32-37 represent even weaker evidence. Authors of case reports employed alternatives to the GRS such as an intubation guide,32,37 a malleable stylet with rotation of the ET tube after passing it below the glottic opening,35 GSV-assisted FOBI,33,34 and GSV-assisted FOBI with ET tube bevel facing posteriorly.36 Below is a summary of these findings. •Controllable Stylet. Authors from Japan reported using a stylet with a controllable tip to help maneuver the ET tube anteriorly to the glottic opening.27 The stylet allowed the operator to direct the ET tube posteriorly to help prevent the ET tube from impacting the anterior airway structures as it passed through the glottic opening into the trachea. •GlideScope-Assisted Fiberoptic Bronchoscopic Intubation. Authors of 3 studies16,24,28 reported success using GSV-assisted FOBI. This technique was described as a teaching tool when the patient is under general anesthesia,24 for awake intubation in difficult-to-intubate situations,28 and in scenarios where the glottic view is adequate but there is difficulty in passing the ET tube into the trachea.16 Authors of 3 case reports reported similar findings.33,34,36 The controllable fiberoptic bronchoscope allows its passage through the glottic opening into the trachea. Unlike a styleted ET tube that can impact the anterior tracheal wall, the fiberoptic bronchoscope can be directed posteriorly, facilitating its placement into the trachea. The ET tube can be passed over the fiberoptic bronchoscope into the trachea. Orienting the ET tube with the bevel facing posteriorly may further faciliate passage of the ET tube.36 Figure 4 demonstrates the GSVassisted FOBI procedure using a manikin. •GlideScope or Similar Device With Malleable Stylet Rather Than GlideRite. Authors of a large retrospective descriptive study suggested a higher success rate using the GRS compared with a malleable stylet in an emergency department setting.22 Other authors reported success using a malleable stylet.14,25 A J-shaped malleable stylet was used in 12 subjects (2 with a suspected difficult airway).25 The investigators reported that this stylet is more effective compared with a stylet with a single 60° bend. The authors also recom- AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 391 392 AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 www.aana.com/aanajournalonline Evidence type/level of evidencea 40 N “C”-shaped intubating guideb Intervention Dupanović et al,19 2010 RCT/level II 120 60 RCT/level II Phua et al,18 2009 16 78 Descriptive study/ level VI Greib et al,16 2007 196 Turkstra et al,17 RCT/level II 2007 RCT/level II Jones et al,15 2007 ETT “reversed-loaded” on MS with 60° bend vs ETT “reversed-loaded” on MS with 90° bend; MS bent just above cuff to the specified angle against the natural concave ETT curve GRS vs ETT with malleable distal tip in “J” shapeg GRS vs MS with 90° bend formed 8 cm from tip Rigid video laryngoscopee-assisted FOI with patient under general anesthesia MS with 60° bend (ETT loaded forward or reverse camber) vs MS with 90° bend (ETT loaded forward or reverse camber) Descriptive study/ > 500 “Hockey stick”-shaped Kramer and MS Osborn,14 2006 level VI Falco-Molmeneu Descriptive study/ et al,13 2006 level VI Evidence source Major findings GSV used as primary intubation method and after failed intubation with DL; twisting the ETT helps navigation around laryngeal structures Used electively; small diameter and memory allows easier passage of guide into trachea Comments 60° Bend 90° Bend Intubation success 51/60 59/60 (subjects intubated ≤ 62 s) Odds ratio for intubation success 10.41 (P < .03) 7 of 9 failures due to inability of 60° stylet to reach glottic opening (all successfully intubated using 90° stylet), 3 other failures due to TTI > 60 s GRSMS Median 42.7 39.9 (34.1-48.2) TTI,f s (IQR) (38.9-56.7) Median 20 (12.0-33.0) 18 (9.5-29.5) VAS ease of intubation, mm (IQR) Comments expressing 43 13 operator dissatisfaction, % Only significant difference between groups was comments expressing operator dissatisfaction (P = .005) ETT with malleable GRS distal tip Mean TTI,h s (SD) 40 (10) 48 (20) Successful intubations 30 28 > 1 intubation attempt 0 2 Only significant difference between groups was mean TTI (P = .08) Randomized block design attempting to control for experience between operators, some blinding of operator and observer; unknown method of sample size determination; application of external laryngeal maneuvers had an inverse effect on intubation success Random assignment, unknown blinding; method of sample size determination not described; 2 subjects required conversion to GRS Concealed random assignment, partial operator blinding, full observer blinding; Other outcomes measured: CL view, attempts, laryngeal manipulation, ETT advanced from stylet by assistant Operator rated procedure as easy in 15 of 16, fair in 1 Used electively; reported vital signs stable during of 16 subjects procedure Angle of ETT bend had impact on TTI, but camber did not Less use of external laryngeal manipulations with 90° 60° Bend 90° Bend bend Mean TTI,d s (SD) 54.4 (28.2) 47.1 (21.2) Mean VAS score 27.3 (23.5) 16.4 (14.2) ease of intubation, mm (SD) Significant difference in TTI, ease of intubation (P < .05) Combination of techniques resulted in successful intubation TTI < 60 s in 38 of 40 subjects; in remaining 2 subjects, modified guide allowed intubation in < 180 s c www.aana.com/aanajournalonline AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 393 178 GRS vs tube exchangerk with placement assisted using vascular forceps GRS vs MS Conventional ETT vs flexible-tip ETTi vs both with GRS GRS vs MS with 90° bend formed 8 cm from tip ConventionalFlexible-tip ETTETT Mean TTI,j s (SE) 14.2 (1.1) 8.2 (1.1) Mean number of 1.3 (1.2) 0.6 (1.2) redirections (SE) Mean VAS ease of 31.0 (4.0) 15.1 (4) intubation, mm (SE) ANCOVA with 2 covariates (CL view and muscle paralysis) Significant difference between groups for TTI (P = .005) and mean VAS ease of intubation (P = .007) GRSMS No. of subjects 322 151 Intubation ultimately 93.5 78.1 successful, % First-attempt success, % 82.9 67.5 Significant difference between groups in intubation success and first-time success (P < .05) Tube exchanger with placement assisted using GRS vascular forceps Intubation on first attempt, %93.2 94.4 Mean TTI, s (SD)l 67.8 (28.7) 66.1 (15.5) No significant difference in intubation on first attempt or mean TTI MS with GRS 90° bend Median TTI,d s (SD) 60 (48-75) 61 (49-75) Ease of intubation 1.5 (1-2) 1.0 (1-2) (1 = easy, 5 = difficult; IQR) No significant difference in TTI, ease of intubation, glottic view, intubation attempts, use of external laryngeal manipulation, or first-attempt success rate Subjects randomized to groups; no blinding; sample size determined using a power analysis; all subjects were successfully intubated using the assigned technique Incidence of oxygen desaturation less with GRS Randomized block design, single-blinded observer; sample size determined using a power analysis Randomized design, operator mostly blinded and observer blinded; sample size determined using a power analysis Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CL, Cormack and Lehane grade; DL, direct laryngoscopy; ETT, endotracheal tube; GRS, GlideRite rigid stylet; GSV, GlideScope video laryngoscope; IQR, interquartile range; MS, malleable stylet, RCT, randomized clinical trial; TTI, time to intubation; VAS, visual analog scale. a Evidence was appraised and classified by level using the method described by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt.12 b Eschmann stylet was modified with a wire core, allowing it to maintain a preset shape. c TTI not defined. d From when GSV passed the lips to when end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) level was ≥ 30 mm Hg. e DCI Video Laryngoscope (Karl Storz). f From when GSV passed the teeth to when end-tidal CO level was ≥ 30 mm Hg. 2 g EndoFlex (Merlyn Associates). h From insertion of GSV to appearance of trace end-tidal CO . 2 i Parker Flex-Tip (Parker Medical). j From optimal glottic view via the GSV to ETT passing through the glottis. k Sheridan T.T.X. (Teleflex). l Insertion of GSV to 3 continuous end-tidal CO curves. 2 Table 1. Randomized Controlled Trials and Descriptive Studies Examining Methods to Increase Intubation Success During Use of the GlideScope Video Laryngoscope RCT/level II 473 Retrospective descriptive study/ level VI Sakles and Kalin,22 2012 Jeon et al,23 2013 58 RCT/level II Radesic et al,21 2012 60 RCT/level II Jones et al,20 2011 Evidence sourceaIntervention Case series Doyle,24 2004 GSV-assisted FOI (8 subjects) Bader et al,25 2006 MS bent into a “J”-shape (12 subjects) Dupanović et al,26 2006 MS bent above cuff to 90° (unable to determine sample size) If intervention failed, coudé-tipped endotracheal introducer was inserted through ETT into the trachea over the introducer Hirabayashi,27 2006 Controllable styletb (unable to determine sample size) 28 Xue et al, 2006 GSV-assisted FOI (13 subjects) Muallem and Baraka,29 2007 Curved pipe stylet and ETT introducerc (4 subjects) Technique used electively ETT can be rotated 90° so bevel faces posteriorly Conklin et al,30 2010 Intubation guide with coudé tip (unable to determine sample size) Ciccozzi et al,31 2013 Intubating introducerd (4 subjects) Case reports Heitz and Mastrando,32 2005 Coudé-tipped, gum elastic bougiee 33 Moore and Wong, 2007 GSV-assisted FOI Vitin and Erdman,34 2007 GSV-assisted FOI Walls et al,35 2010 MS shaped to the GSV blade, 180º clockwise rotation of ETT after passing through glottis Sharma et al,36 2010 GSV-assisted FOI with ETT bevel facing posteriorly O’Mahony and Pagano,37 2013 Straight end of ETT introducerf in a “C” shape Table 2. Case Series and Case Reports Describing Successful Intubation Methods During Use of the GlideScope Video Laryngoscope Abbreviations: ETT, endotracheal tube; FOI, fiberoptic intubation; GSV, GlideScope video laryngoscope; MS, malleable stylet. a Evidence was appraised and classified by level using the method described by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt.12 b StyletScope (Nihon Kohden Corp). c Muallem ET Tube Introducer (VBM Medizintechnik). d Frova Intubating Introducer (Cook Medical). e Eschmann stylet modified with a wire core allowing it to maintain a preset shape. f SunMed Endotracheal Tube Introducer (Azimuth Corp). mended an additional 90° bend to the proximal end of the ET tube because it may prevent the ET tube from impacting the anterior tracheal wall. Authors of a case series reported success using a malleable stylet with a 90° bend promixal to the cuff of the ET tube.26 If this is not successful, they recommended instead using an intubation guide, passing the coudé tip of the guide into the trachea. The ET tube can then be passed over the guide into the trachea. They, too, recommended an additional 90° bend to the proximal end of the ET tube to help avoid impacting the anterior tracheal wall. The exact number of subjects was not reported. Other authors reported using a malleable stylet shaped like a hockey stick to facilitate intubations in more than 500 awake and anesthetized subjects.14 They recommended twisting the ET tube to navigate around laryngeal structures and withdrawing the stylet during passage through the glottic opening. •GlideScope With Intubation Guide Rather Than GlideRite. A malleable C-shaped ET tube introducer was used instead of the GRS.13 The time to intubation was less than 60 seconds in 38 of 40 subjects, and 2 subjects were intubated in 180 seconds after modifying curvature of the guide. A modified intubating guide was described 394 AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 in another case series involving 4 subjects.29 They also oriented the ET tube so the bevel faced posteriorly, aiding passage of the ET tube through the glottis into the trachea. In 4 other subjects, an intubation guide was used after failure using direct laryngoscopy and the GSV with the GRS.31 Two case reports also described succesful use of this technique.32,37 The narrow gauge and malleable yet flexible nature of the intubating guides probably facilitated passage into the trachea, and the ET tube was then passed over the guide. •Rotating Endotracheal Tube After Passing Below Glottic Opening. A subject assessed as having a normal airway was unable to be intubated with use of the GRS. A sharp posterior tracheal angulation in relation to the larynx was noted on GSV inspection. Successful intubation was accomplished by rotating the ET tube 180° clockwise after the ET tube loaded on a malleable stylet was passed through the glottic opening.35 This must be done with extreme care because of the risk of tracheal injury. Conclusion Despite an adequate glottic view, passage of the ET tube into the trachea can be difficult. Reasons for this difficulty include not being able to maneuver the tip of the www.aana.com/aanajournalonline Figure 1. Endotracheal tube loaded onto a malleable stylet forward camber. From top to bottom: stylet and endotracheal tube, endotracheal tube loaded onto stylet, endotracheal tube advanced off stylet. Note how tip of endotracheal tube tends to advance anteriorly. Figure 3. Parker Flex-Tip endotracheal tube. Figure 2. Endotracheal tube loaded onto a malleable style reverse camber, or “reverse loaded.” From top to bottom: stylet and endotracheal tube, endotracheal tube loaded onto stylet, endotracheal tube advanced off stylet. Note how tip of endotracheal tube tends to advance posteriorly. ET tube through the glottic opening or the ET tube tip impinging on airway structures, including the anterior aspects of the larynx or trachea.31 www.aana.com/aanajournalonline Findings from RCTs represent the highest level evidence. Findings from an RCT suggested that using a flexible-tipped ET tube with the GRS may increase intubation success.21 Authors of 2 studies found no benefit of using a malleable stylet with a 90° bend formed proximal to the ET tube cuff.17,20 There was also no benefit of “reverse camber” loading the ET tube onto the stylet.15,19 However, if using a malleable stylet, a 90° bend was preferable to a 60° bend regardless if the ET tube was loaded forward camber or reverse camber.15,19 A malleable stylet with a “J” bend was not found to be superior to the GRS but this study may have been underpowered.18 Using an ET tube exchanger with a vascular forceps did not result in an increase in first attempt intubations or a decrease in the time to intubation compared with the GRS.23 AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 395 than a conventional ET tube with the GRS.18 The generalizability of these findings must be viewed with caution. Like any technique requiring psychomotor skill, an individual provider may be capable with a particular technique because of experience using the technique. Providers must consider the additional time required to use these techniques. The risks and benefits must be considered particularly if using a technique not recommended by the device manufacturer. Cost and personnel requirements must be considered such as the additional expensive equipment and personnel required for the GSV-FOBI technique. Further rigorous investigations should be conducted examining methods to increase success of intubation using the GSV. Until then, providers should be aware of methods that may increase success when encountering problems while using the GSV. These alternatives should be practiced in a controlled setting before being employed in an emergency situation. REFERENCES Figure 4. GlideScope-assisted fiberoptic bronchoscopic intubation in a simulated setting. A, GlideScope operator and fiberoptic bronchoscope operator. B, Fiberoptic bronchoscope passed through endotracheal tube and entering the glottic opening. C, Fiberoptic bronchoscope in the trachea, with endotracheal tube passing over the fiberoptic bronchoscope through the glottic opening and into the trachea. Findings from lower-level evidence suggested a number of alternatives to the GRS. Authors of a descriptive study,16 case series,24,28 and case reports33,34,36 suggested using a fiberoptic bronchoscope in conjunction with the GSV increases intubation success. The fiberoptic bronchoscope can be viewed via the GSV monitor and the controls of the fiberoptic bronchoscope used to maneuver it to the glottic opening and into the trachea. This combination of visualization and controllability reduce trauma to delicate airway structures.36 Rotating the ET tube after passing below the glottic opening35 and using a controllable stylet could increase intubation success.27 Use of the fiberoptic bronchoscope with GSV has also been described in a technical report.39 Descriptive studies,13 case series,29-31 and case reports32,37 supported the use of an intubation guide. It may be helpful to orient the ET tube bevel posteriorly when one uses an intubation guide.29 There was no reported benefit of using a malleable tipped ET tube rather 396 AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 1. Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, et al; American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):251-270. 2. Rai MR, Dering A, Verghese C. The Glidescope system: a clinical assessment of performance. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(1):60-64. 3. GlideScope GVL and Cobalt Quick Reference Guide. Bothwell, WA: Verathon Medical Inc; 2009-2011. 4. Cooper RM. Use of a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in the management of a difficult airway. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50(6):611-613. 5. Cooper RM, Pacey JA, Bishop MJ, McCluskey SA. Early clinical experience with a new videolaryngoscope (GlideScope) in 728 patients. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52(2):191-198. 6. Sun DA, Warriner CB, Parsons DG, Klein R, Umedaly HS, Moult M. The GlideScope Video Laryngoscope: randomized clinical trial in 200 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(3):381-384. 7. Marrel J, Blanc C, Frascarolo P, Magnusson L. Videolaryngoscopy improves intubation condition in morbidly obese patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2007;24(12):1045-1049. 8. Kaplan MB, Hagberg CA, Ward DS, et al. Comparison of direct and video-assisted views of the larynx during routine intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18(5):357-362. 9. Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984;39(11):1105-1111. 10. Glick DB, Cooper RM, Ovassiapian A, eds. The Difficult Airway: An Atlas of Tools and Techniques for Clinical Management. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2013. 11. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The wellbuilt clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12-A13. 12. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Health Care: A Guide to Best Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2011. 13.Falco-Molmeneu E, Ramirez-Montero F, Carregui-Tuson R, Santamaria-Arribas N, Gallen-Jaime T, Vila-Sanchez M. The modified Eschmann guide to facilitate tracheal intubation using the GlideScope. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(6):633-634. 14. Kramer DC, Osborn IP. More maneuvers to facilitate tracheal intubation with the GlideScope [letter]. Can J Anesth. 2006;53(7):737-740. 15. Jones PM, Turkstra TP, Armstrong KP, et al. Effect of stylet angula- www.aana.com/aanajournalonline tion and endotracheal tube camber on time to intubation with the GlideScope. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54(1):21-27. 16.Greib N, Stojeba N, Dow WA, Henderson J, Diemunsch PA. A combined rigid videolaryngoscopy-flexible fibrescopy intubation technique under general anesthesia [letter]. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54(6):492-493. 17. Turkstra TP, Harle CC, Armstrong KP, et al. The GlideScope-specific rigid stylet and standard malleable stylet are equally effective for GlideScope use. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54(11):891-896. 18. Phua DSK, Wang CF, Yoong CS. A preliminary evaluation of the Endoflex endotracheal tube as an alternative to a rigid styletted tube for GlideScope intubations [letter]. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37(2):326-327. 19.Dupanović M, Isaacson SA, Borovcanin Z, et al. Clinical comparison of two stylet angles for orotracheal intubation with the GlideScope video laryngoscope. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(5):352-359. 20. Jones PM, Loh FL, Youssef HN, Turkstra TP. A randomized comparison of the GlideRite Rigid Stylet to a malleable stylet for orotracheal intubation by novices using the GlideScope. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(3):256-261. 21.Radesic BP, Winkelman C, Einsporn R, Kless J. Ease of intubation with the Parker Flex-Tip or a standard Mallinckrodt endotracheal tube using a video laryngoscope (GlideScope). AANA J. 2012;80(5):363-372. 22. Sakles JC, Kalin L. The effect of stylet choice on the success rate of intubation using the GlideScope video laryngoscope in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):235-238. 23.Jeon WJ, Shim JH, Cho SY, Baek SJ. Stylet- or forceps-guided tube exchanger to facilitate GlideScope intubation in simulated difficult intubations—a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2013;68(6):585-590. 24. Doyle DJ. GlideScope-assisted fiberoptic intubation: a new airway teaching method [letter]. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(5):1252. 25. Bader SO, Heitz JW, Audu PB. Tracheal intubation with the GlidesScope [sic] videolaryngoscope, using a ‘J’ shaped endotracheal tube. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(6):634-635. 26.Dupanović M, Diachun CA, Isaacson SA, Layer D. Intubation with the GlideScope videolaryngoscope using the ‘gear stick technique’. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(2):213-214. 27. Hirabayashi Y. The StyletScope facilitates tracheal intubation with the GlideScope. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(12):1263-1264. 28. Xue FS, Li CW, Zhang GH, Li XY, Sun HT, Liu KP. GlideScopeassisted awake fibreoptic intubation: initial experience in 13 patients [letter]. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(10):1014-1015. 29. Muallem M, Baraka A. Tracheal intubation using the GlideScope with a combined curved pipe stylet, and endotracheal tube introducer [letter]. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54(1):77-78. 30. Conklin LD, Cox WS, Blank RS. Endotracheal tube introducer-assisted intubation with the GlideScope video laryngoscope. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(4):303-305. 31. Ciccozzi A, Angeletti C, Guetti C, et al. GlideScope and Frova introducer www.aana.com/aanajournalonline for difficult airway management. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2013;2013:717928. 32. Heitz JW, Mastrando D. The use of a gum elastic bougie in combination with a videolaryngoscope. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17(5):408-409. 33. Moore MS, Wong AB. GlideScope intubation assisted by fiberoptic scope [letter]. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(4):885. 34. Vitin AA, Erdman JE. A difficult airway case with GlideScope-assisted fiberoptic intubation [letter]. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(7):564-565. 35. Walls RM, Samuels-Kalow M, Perkins A. A new maneuver for endotracheal tube insertion during difficult GlideScope intubation. J Emerg Med. 2010;39(1):86-88. 36. Sharma D, Kim LJ, Ghodke B. Successful airway management with combined use of Glidescope videolaryngoscope and fiberoptic bronchoscope in a patient with Cowden syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(1):253-255. 37. O’Mahony CJ, Pagano PP. Facilitating GlideScope intubation with the straight end of an endotracheal tube introducer [letter]. J Clin Anesth. 2013;25(7):603-604. 38. Corda DM, Riutort KT, Leone AJ, Qureshi MK, Heckman MG, Brull SJ. Effect of jaw thrust and cricoid pressure maneuvers on glottic visualization during GlideScope videolaryngoscopy. J Anesth. 2012;26(3):362-368. 39.Weissbrod PA, Merati AL. Reducing injury during video-assisted endotracheal intubation: the ‘smart stylet’ concept. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(11):2391-2393. AUTHORS Darrell Nemec, CRNA, DNAP, is a staff nurse anesthetist with the Edward Hines Jr Veterans Affairs Hospital in Hines, Illinois. The author was a student in the Doctorate of Nurse Anesthesia Practice program at Texas Wesleyan University in Fort Worth, Texas, at the time this article was written. Paul N. Austin, CRNA, PhD, is a professor in the Graduate Programs of Nurse Anesthesia at Texas Wesleyan University. Loraine S. Silvestro, PhD, is an associate professor of pharmacology in the Graduate Programs of Nurse Anesthesia at Texas Wesleyan University. DISCLOSURES The authors have declared no financial relationships with any commercial interest related to the content of this activity. The authors did not discuss off-label use within the article. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr Nemec would like the thank the following individuals at Edward Hines Jr Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines, Illinois, for their assistance: Fred Luchetti, MD, Chief, Surgical Services; Usha Kolpe, MD; Molly Vadakara, CRNA; Sabin Oana, MD; Reena Varkey, RN, Simulation Laboratory; Daniel Duverney, Medical Media Service; and the library staff. AANA Journal December 2015 Vol. 83, No. 6 397