Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Etiologies and Treatment 2006

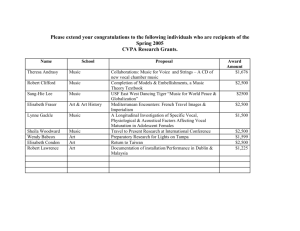

advertisement