winding up and dissolution of entities in troubled times

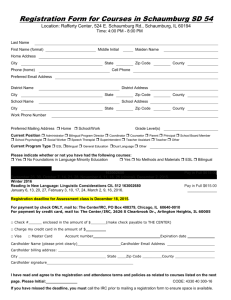

advertisement