Character centered leadership: Muhammad (p) as an ethical role

advertisement

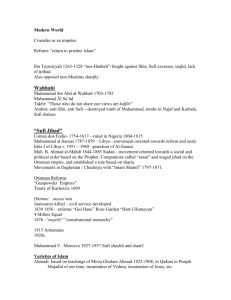

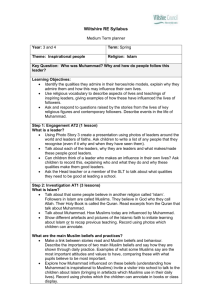

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/0262-1711.htm ACADEMIC CONTRIBUTIONS Character centered leadership: Muhammad (p) as an ethical role model for CEOs Character centered leadership 1003 Rafik I. Beekun Managerial Sciences Department, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, USA Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to examine the leadership style of Muhammad (p) within a character-centric framework as a useful alternative to the transactional, self-centered model and the value-neutral transformational approach that currently permeate business management. The author differentiates such perspectives from the character-centered, moral approach to leadership suggested by the Qur’an and modeled by Muhammad (p), and proposes that this approach may be of practical use to CEOs. Design/methodology/approach – A conceptual, comparative discussion of Muhammad’s leadership style based on the primary Islamic sources is shown to have practical implications for the leadership process in management. Findings – The current malaise in business leadership can be resolved by a new focus on character and on virtues. Practical implications – The character-centered, moral approach of Muhammad provides exemplars of virtues and behaviors that, if emulated by CEOs, may help pre-empt potentially self-serving, individualistic and narcissistic tendencies. Originality/value – The leadership model of Muhammad has been applied to a number of arenas before, but this is the first attempt at explicating the Qur’anic emphasis on the role-modeling aspects of his character (khuluqin azeem). When fully expounded, it is likely to offer a more virtue-centric alternative to transactional and/or transformational approaches to leadership and their associated relativistic values. Keywords Islam, Ethics, Behaviour, Transformational leadership, Character, Virtues, Muhammad, Servant leadership, Practical wisdom Paper type Conceptual paper 1. Introduction The litany of unethical business actions resulting from poor leadership at global companies such as Enron, Arthur Andersen and numerous others in Europe and elsewhere, the enactment of laws such as Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) in the USA and the UK Bribery Act (2010), the potential international bribery blacklisting of British firms (Leigh, 2011) and the renewed global emphasis on anti-bribery and corruption compliance activities (KPMG, 2011) suggest that dominant leadership models, such as the transactional and the transformational approaches to leadership, need to be rethought in spite of the relative “effectiveness” of these approaches (Groves and LaRocca, 2011). Although transformational leadership counterbalances the potentially self-serving nature of transactional leadership, research indicates that it too may be hampered by flaws (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999; Howell and Avolio, 1992). For example, transformational leadership does not ensure behavioral ethicality or an emphasis on moral values (Groves and LaRocca, 2011; Dubrin, 2012). A potential response to these Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Journal of Management Development Vol. 31 No. 10, 2012 pp. 1003-1020 r Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0262-1711 DOI 10.1108/02621711211281799 JMD 31,10 1004 concerns has been the focus on responsible leadership, but that perspective – focussing on a single virtue – has also provided an incomplete resolution to the weaknesses in previous leadership research (Pruzan and Miller, 2006). Exacerbating the above issues is the fact that leaders find it difficult to ensure that their people abide by values and ethics (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 2011). Business leaders still hold to the idea that greed pays as long as they can get by governmental watchdogs. This belief may result partly from the dichotomy between ethical and unethical values, and the frequent conflation of values and virtues – two terms that are not interchangeable (Melé, 2011). To address these deficiencies, my paper examines the virtues underlying Muhammad’s (p)[1] leadership style within a character-centric framework, and aims to provide practical insights for CEOs and other leaders. 2. Why character-centered leadership? Over the past decades, different approaches to leadership have been proposed to improve leaders’ effectiveness (Dubrin, 2012), but have each their own ethical slip-ups. As indicated by Bass and Steidlmeier (1999), transactional leadership emphasizes the idea of social exchange processes based upon contingent reinforcement. Followers perform a task for the leader in return for the rewards that he/she can deliver. Unfortunately, this perspective may engender an exclusive pursuit of one’s own interests and be therefore problematic (Rosenthal and Buchholz, 1995). By contrast, transformational leadership (Burns, 1978; Bass, 1985) focusses on the major, positive changes that leaders bring about. The transformational leader influences his/her followers to look beyond their self-interests and to focus instead on the collective good. Although Burns (1978) had suggested that a transformational leader should be morally uplifting, Bass (1985) initially proposed that transformational leaders could be either “virtuous” or “villainous” depending on their values. He later reversed himself by distinguishing between “authentic transformational leaders” and “pseudo-transformational leaders” (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999). One cannot be sure then whether a transformational leader abides by values that are either moral or immoral. Reflecting on the gaps in transactional and transformational leadership, Maak and Pless (2006) and Groves and LaRocca (2011) have recently emphasized the concept of responsible leadership, suggesting that one element missing from previous models of leadership is the responsibility element. Waldman and Galvin (2008) assert that responsibility is “geared towards the specific concerns of others, an obligation to act on those standards, and some measure of accountability for the consequences of one’s actions.” What if the “others” are members of a gang, terrorists or other types of criminals? What if the standards by which one is to act are criminal standards? Since responsibility is a necessary but not sufficient condition for ethical leadership, there are likely to be other virtues that relate to moral judgments and acts. Indeed, Bass and Steidlmeier (1999, p. 3) contend that the key issue in making moral judgments (and acting morally) depends on the “legitimacy of the grounding worldview, and beliefs that grounds a set of moral values and criteria.” While Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) and Ciulla (2006) have looked at moral character as discussed by Aristotle and Confucius, I contend like Beekun and Badawi (1999) and Kriger and Seng (2005) that there is a character-based model embedded within the Qur’an and the Sunnah or Hadith[2]. The primary purpose of my paper then is to uncover the character-centric model of Muhammad and to outline a core set of leadership education principles within the Supplied by the NIOC Central Library context of practical wisdom. For the purposes of my paper, I will use Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (2011, p. 60) definition of practical wisdom as “tacit knowledge acquired from experience that enables people to make prudent judgments and take actions based on the actual situation, guided by values and morals.” Thus, practical wisdom emphasizes the importance of flexible and contingent decision making while seeking advice from people with the relevant competencies and moral character. Other important elements of practical wisdom involve the sincere attitude to do what is right, the search of balance between opposing values (Melé, 2011) and the application of ethical principles. Since the implementation of ethics is a function of a leader’s character (Halverson, 2004), and since Aristotle suggests that “the person of good character perceives a situation rightly – that is, take proper account of the salient features” (Hartman, 2006, p. 74), it is not surprising that character is a critical requirement for leadership effectiveness (Mintzberg, 2004). Accordingly, then, in seeking to offer practical advice to CEOs and other leaders based on Muhammad’s (p) leadership model, I will now explore key virtues at the core of his character. For the purposes of my paper, I will use Aristotle’s definition of character as the moral dimension of a person (Melé, 2011). 3. Character-centered leadership To situate the leadership style of Muhammad (p), I must first focus on a key verse in the Qur’an (68:4) where God describes him as follows: And you (Muhammad) stand as an exalted standard of character. This verse describes the very core of Muhammad’s (p) leadership. The Arabic term khuluq used in this verse means “character.” Abu Laylah (1990) states that the word khuluq (plural akhlaq) means “character, natural disposition or innate temper.” In contrast to the word fitrah (Qur’an, 30:30) which describes the nature with which a person is born, khuluq (26:137) connotes an additional meaning, that of an acquired or learned “custom” or “habit.” Over time, a “habit” or “custom” may become second nature to a person. Overall, when juxtaposing fitrah and khuluq, Abu Laylah suggests that while a common core of morality (fitrah) is created in us when we are created, we can acquire morality through education and socialization – by properly emulating the model or behavioral pattern of Muhammad (p). The Qur’an emphasizes the modeling dimension of Muhammad’s character-centric exemplar. In two verses, the Qur’an (68:4) stresses this aspect of the character of Muhammad when it explicitly states (33:21) that he is the “ouswatoun hasana” (excellent model) mankind is to follow, and then reaffirms that mankind is to learn wisdom (hikmah) from him: [y] We have sent among you a Messenger of your own to recite Our revelations to you, purify you and teach you the Scripture, wisdom, and [other] things you did not know (Qur’an, 2:151). One possible definition of hikmah which correlates with Aristotle’s is given by Burhan (2012) as “a total insight and having sound judgment concerning a matter or situation through understanding cause and effect phenomena.” Picking a model and emulating his behavior are clearly an important means of learning, but Islam suggests that mimicry alone does not guarantee wisdom; character and virtue, too, are essential. In describing his character modeling mission, Muhammad (p) repeatedly refers to the concept of akhlaq, and relies on both above-mentioned meanings of the term. In a Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Character centered leadership 1005 JMD 31,10 hadith that reflects the authentic transformational nature of his mission, the Prophet (p) stated: I was not sent except to perfect moral characters[3]. 1006 Thus, the mission of the Prophet (p) as an “exalted standard of character” is to help men and women improve their own moral character with the Qur’an and his traditions as their guide. 4. Muhammad’s (p) character Muhammad’s (p) character was virtue centric, and is consistent with the Qur’an. Indeed, when ‘Aisha (ra) was asked about the character of the Prophet (p), she answered, “Verily the character of the Prophet of God was the Qur’an.[4]” The character-centered model of Muhammad (p) is also consistent with Aristotelian thought where ethics centers around virtues and virtues derive from character. In this paper, I will adopt Alasdair Maclntyre’s (1984) definition of virtue as being “qualities that both enable and predispose a person to live a good life” and lead them to do the “right” thing given any situational context[5]. Known as As-Siddiq (the truthful) and Al-Ameen (the trustworthy) long before he received divine inspiration, Muhammad (p) modeled core virtues that defined his character and his behavior: truthfulness and integrity, trustworthiness, justice, benevolence, humility, kindness and sabr (patience). These will be described briefly here. Truthfulness and integrity Muhammad’s (p) truthfulness was so well known that even after he claimed Prophethood, his enemies would still not accuse him of lying. Modeling the behavior he preached to others, He (p) always encouraged truthfulness and integrity of character. For example, he once declared: Three are the signs of a hypocrite: When he speaks, he lies; when he makes a promise, he breaks it; and when he is trusted, he betrays his trust (Abu Hurairah, in Bukhari and Muslim). The above hadith is interesting in that it defines integrity (the lack of hypocrisy) as a “synthesis of virtues” (Melé, 2011): truthfulness, promise-keeping and trustworthiness. Integrity, in fact, is the number one attribute by which followers of the most effective leaders assess the effectiveness of their leader (Kouzes and Posner, 1995). Since a leader with integrity will be steadfastly upright, his/her followers will trust him/her. Trustworthiness The above hadith also highlights the second core value characterizing Muhammad: amana or trustworthiness. It correlates with Dubrin’s (2012) discussion of the characteristics of effective transformational leaders. In spite of offers of vast wealth and power, Muhammad (p) never compromised his cause, nor did he ever cheat anybody. Amazingly, the very adversaries who were plotting to kill him in Makkah were the same people who had entrusted him with their property. An additional dimension of amana relates to the concept of man’s role of trustee on earth. As such, he must bear responsibility for his actions. The wealth and other resources that man has access to are not his, but have been loaned to him by God as tools to fulfill the responsibilities of the trusteeship. Like any other person, a CEO is accountable for his/her actions, and must devolve the responsibilities associated with his/her position toward other stakeholders (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Justice Justice is described by two words in the Qur’an: ‘adl and qist; ‘adl means “equity, balance” whereas qist refers to the highest level of justice. In the Qur’an, Muslims are encouraged by God to behave justly toward all: “Be just! For justice is nearest to piety” (Qur’an, 5:8). Consistent with Melé’s (2011) definition of justice as “the perpetual and constant will to render to each his or her right,” Muhammad (p) never dealt with anybody in a partial manner. In a famous incident involving a lady thief, he rejected any intercession attempt decrying the selective justice administered prior to him. Benevolence (Ihsan) It describes an action that benefits persons other than those from whom the action proceeds without any obligation, and issues from the recognition and consideration for human dignity (Melé, 2011). In contrasting the concepts of Ihsan (benevolence) and ‘adl ( justice), Al-Qurtubi (1966) expounds on the Qur’anic verse “Lo! God enjoins justice and kindness” (16:90), and suggests that ‘adl ( justice) is mandatory while Ihsan (benevolence) is what is above and beyond the mandatory. Whereas CEOs and their followers sometimes self-destruct because of lingering enmities, Muhammad (p) acted benevolently even with respect to those who had committed grievous and barbaric acts against his family. Humility According to Collins (2005), one of the key attributes of the CEOs of the most effective firms is level 5 leadership which centers on humility. Being humble does not mean that one is submissive and easily swayed. While preparing for the battle of Al Ahzab, the Prophet Muhammad (p) joined his companions in digging the ditch around Madinah and carried bowls of earth on his head. At home, he milked his own goats, mended his own clothing, and slept on the floor on a very thin mat. Kindness A leader’s role is not that of a bully wielding a big stick. Many famous CEOs have acquired notoriety because of their harsh treatment of their subordinates, e.g. Jack Welch[6] (New York Times, 2011), or Steve Jobs[7] (Nocera, 2011). By contrast, the Prophet (p) advised his followers to treat a worker or servant kindly – as he did. As narrated by Amr Ibn Harayth: If you show kindness to your servant while employing him in some task, this will weigh heavily in your favor on the Day of Judgment [y]. Patience As Safi (1995) points out, sabr is the type of endurance leaders need during natural disasters ordained by God. During a three-year long total boycott of the fledgling Muslim community in Makkah, the Prophet strengthened his followers through his exemplary sabr: When we complained to God’s Messenger (p) of hunger and raised our clothes to show we were each carrying a stone over the belly, God’s Messenger (p) raised his clothes and showed that he had two stones on his belly[8]. Overall, Muhammad modeled key moral virtues integral to his character by practicing them tangibly. To demonstrate that Muhammad (p) not only preached virtuous behavior but also practiced it, I will now analyze his character-centric model of Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Character centered leadership 1007 JMD 31,10 leadership in light of the authentic transformational leadership and servant leadership literature. This analysis will then enable me to extract elements of practical wisdom for CEOs and other leaders. 1008 5. Muhammad’s character-centric style of leadership As an authentic transformational leader (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999), Muhammad’s mission was to change the jahiliyyah[9] culture in pre-Islamic Arabia and, on a broader scale, the world across time. The process by which Muhammad (p) was able to bring about this change is described in Figure 1 (adapted from Beekun, 2008 and based on Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999 and Dubrin, 2012). Raising people’s awareness Muhammad (p) increased awareness of what it is right, just and halal (lawful) during a period of jahiliyyah or ignorance. Describing this pre-Islamic state of affairs, Ja’far ibn Abi Talib told the ruler of Abyssinia: “O king! We used to drink blood, eat of carrion, commit fornication, steal, kill one another and plunder. The powerful used to oppress the weak. We used to do many other things shameful and despicable” (Bukhari, Wasa’ya’). Against this backdrop, Muhammad (p) spent his lifetime teaching and mentoring his followers in the core Islamic virtues and values. Help people look beyond their self-interest Muhammad (p) stressed the universal brotherhood of mankind, enjoined benevolence, kindness and justice and argued against the egoism that permeated the times. He posited that practices such as infanticide should not be acceptable simply because they • Principle of intention • Principle of taqwa (awe) • Principle of gratitude • Principle of shura • Principle of accountability Transformational leadership 1. Raise awareness 2. Help people look beyond their self-interests 3. Intellectual stimulation 4. Idealized influence or charisma 5. Individual consideration 6. Inspirational motivation Moral character of muhammad (p) Servant leadership 1. Service before self 2. Listening as a means of affirmation 3. Creating trust 4. Focus on what is feasible to accomplish 5. Lend a hand Figure 1. Muhammad (p) as the Ouswatoun Hasana (excellent model) for leaders Supplied by the NIOC Central Library had been passed down from one’s ancestors. These were not only morally unacceptable, but were also morally unkind and unjust: None of you truly believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself (Hadith #13 in An Nawawi). Challenging their clan-centric parochialism, Muhammad (p) encouraged his followers – the Muhajirin and the Ansar – to look at the “big picture” for the sake of the Ummah. Blood ties were to be superseded by the ties of the brotherhood of faith strengthened by the virtues that the Prophet’s (p) himself lived by. Intellectual stimulation The intellectual stimulation necessary to challenge jahiliyyah was divinely ordained in the first word of revelation: “Iqra” meaning “Read!” This command, coming to an unlettered Prophet (p) implied that believers should use their intellectual and spiritual faculties to reflect about God’s signs present throughout His creation. In the manner of authentic transformational leaders (Avolio and Bass, 1988), Muhammad (p) offered his followers a new worldview. Besides raising their spiritual awareness, he (p) urged them to engage themselves in learning and to excel in whatever field they pursued: He who issues forth in search of knowledge is busy in the cause of God till he returns from his quest (as reported by Anas Ibn Malik in Al Tirmidhi, hadith #420). They were to search for and acquire knowledge not for self-aggrandizement, but rather to get closer to, and to serve their Creator. Taking these injunctions to heart, Muslims developed the first universities and led in many scientific areas for centuries (Said, 1983). Idealized influence or charisma According to Stone et al. (2004), leaders who demonstrate integrity in ethical conduct become role models that followers admire, respect and pattern themselves after. Charisma, however, can have either a positive or a dark side. Ethical charismatic leaders work to develop their followers into leaders, learn from criticism and rely on an internal moral standard. Unethical charismatic leaders are motivated by self-interest, censure critical or opposing views and lack an internal moral compass. As indicated earlier (Qur’an, 68:4), Muhammad (p) was an ethical charismatic leader, and this is validated by the virtuous life he lived. Individual consideration and attention Muhammad (p) paid close attention to the personal differences among his followers (Humphreys, 2005). He understood that each follower had different needs and that those needs changed over time. He reached out to everybody with kindness and benevolence, including his worst detractors. One need only compare the pre-Islamic Umar (who was about to assassinate him) to the Muslim Umar (r)[10] to understand the effect that Muhammad (p) had as a role model and coach on some of his toughest opponents. He treated them fairly, but differently depending on his assessment of their maturity level and readiness – as when he refused to appoint Abu Dhar to an administrative post based on his “inability to manage the affairs of the people” (Muslim, Imara, 16-17). Inspirational motivation This dimension of transformational leadership (Avolio and Bass, 1991) is characterized by the communication of high expectations, the use of symbols to focus efforts and the Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Character centered leadership 1009 JMD 31,10 1010 enunciation of important goals in simple terms. Such behavior increases the selfconfidence of followers. Inspirational leaders often provide encouragement during difficult times and set the group standard as far as work ethic is concerned – as when the Muslims were being harassed and several were being tortured and put to death in the cruelest manner. Muhammad (p) refused to react vindictively and kept his companions focussed on their higher common purpose. 6. Problems with transformational leadership Howell and Avolio (1992) and Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) have indicated that there are potential ethical problems with transformational leadership. First, transformational leaders may enhance their positives and downplay their weaknesses, and adopt the values which they believe fit the implicit theories of leadership of their followers. However, Muhammad (p) was forthright about his values and never compromised them. Had he been morally corrupt, he would have adopted the corrupt values of the elite in Makkah and accepted their offers of immense wealth and power. He never yielded to their demands. Second, contrary to transactional leadership, there are no checks and balances for transformational leaders, and there may be an unhealthy concentration of power and authority at the top. In rebutting this argument, one notes Muhammad (p) sought shura (consultation with others) about key issues whenever there was no direct revelation from God. Most importantly, there was never an occasion when he sought shura that he did not follow the shura decision even when he may have personally disagreed with it. Third, followers may be manipulated into following their leader’s interests rather than attending to their own personal needs. The fact is that, as enjoined in the Qur’an (Surah 2:256), Muhammad (p) never compelled anyone to embrace Islam against his or her will. He never ordered his companions to give away their possessions to him. He never appointed any of his family as his heir apparent. He never built himself or lived in palaces like other contemporary leaders. Clearly, although Muhammad (p) meets several of the parameters of transformational leadership, his character-centered model was based on virtues and moral values that extend beyond this leadership perspective, and rise above its potential deficiencies. A more recent leadership theory that may help us understand some additional elements of Muhammad’s leadership model is servant leadership. 7. Muhammad (p) as a servant leader According to Greenleaf (1977), the servant leader focusses on the needs of others rather than his or her own needs. McMinn (2001) suggests that servant leaders develop people whereas Farling et al. (1999) indicate that such leaders also provide vision, gain credibility and trust from their followers. I will now discuss several key attributes of servant leaders – as they relate to Muhammad (p) (Humphreys, 2005; Dubrin, 2012). Service before self A servant leader is not interested in obtaining power, status or wealth. He/she wishes to do what is morally right even when it may cost him/her personally. Muhammad (p) stated that “a leader of the nation is their servant” (sayyid al qawn khadimuhum). Benevolent to the core, Muhammad (p) constantly sought his companions’ welfare and labored to guide them toward what is good. Status was unimportant to him. During the writing of the Hudaybiya treaty, the Prophet (p) dictated these words: “This is from Muhammad, the Messenger of God.” When the Quraish’s delegate objected, the Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Prophet (p) promptly requested his scribe to write down “Muhammad, son of Abdullah” instead. This direct attempt to humiliate him did not dent his humility and patience. Neither wealth nor status attracted the Prophet (p). The change in his social status from that of a trader to the head of the state in Madinah did not bring any alteration in his modest living. Anas (r) said that the Prophet would accept an invitation even if he was presented with barley bread and soup whose taste had changed. Anas also reported the Prophet (p) as saying: I am God’s servant, I eat like a servant and sit like a servant. Listening as a means of affirmation Muhammad (p) did not seek to impose himself on others unless it was a matter of divine revelation. He would stay quiet while first listening to the queries from his followers, and then respond appropriately. Creating trust As indicated by Greenleaf (1977), the servant leader is above all honest with others, focussing on their needs and earning their trust. As indicated before, Muhammad (p) was known as “al-ameen,” the trustworthy. He was always a man of his word, never cheated or stole from anybody and spoke the truth at all times – something even his enemies grudgingly acknowledged. Focus on what is feasible to accomplish The servant leader neither seeks to accomplish everything, nor does he take the most difficult route to do it. Aisha (ra) narrated that whenever God’s Apostle was given the choice of one of two matters, he would choose the easier of the two (Bukhari, 4:760). Muhammad (p) also used gradualism: he knew that he could not take his message to the whole of Arabia immediately; rather he first had to proceed covertly until God allowed him to go public. Lending a hand The servant leader is a Good Samaritan – he or she searches for opportunities to do good. Muhammad’s (p) kindness and benevolence were limitless. He was always helping the poor and the needy. ‘Abdullah ibn Abi Awfa reported that the Prophet (p) never disdained to go with a widow to accomplish her tasks. Jabir stated that the Prophet used to slow down his pace for the sake of the weak and also prayed for them. Clearly, then, Muhammad’s (p) character-centered leadership modeled the virtues he preached, and is unique in that he blends elements of authentic (ethical) transformational leadership with servant leadership. I have contrasted in Table AI (see Appendix) these two dominant leadership perspectives with character-centered leadership. This model of leadership is moderated by what five principles critical to Islam – intention, taqwa, gratitude, shura and accountability. These principles are briefly discussed here: . Intention (nyat): in Islam, intentions are critical in judging the behavior of any person including leaders. Muhammad (p) is reported to have said: O people! Behold, the action(s) are but (judged) by intention(s) and every man shall have but that which he intended[11]. Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Character centered leadership 1011 JMD 31,10 The above hadith is important because a major criticism leveled against the transformational leaders is that they engage in impression management, and that their actions are only for show. The character-centric model of Muhammad (p) focusses on intentions, thus negating pseudo-transformational leadership. . 1012 . . . Taqwa (awe): Taqwa is the all-encompassing, inner consciousness of one’s duty toward Him and the awareness of one’s accountability toward Him (Beekun and Badawi, 1999). A leader’s awe and fear of God will lead him to remember who he is ultimately accountable to, and avoid any behavior that may be outside the limits prescribed by God (2:2-5). Character-centered leaders know that even if they foil the justice of man, they cannot dodge that of God. Unethical transformational and pseudo-servant leaders behave unethically because they believe they are beyond checks and balances (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999). Taqwa would pre-empt such abuses. Gratitude is a key element of Islam since it reminds one and all of the bounties that God has granted humankind (e.g. 3:103). A leader or follower who does not feel gratitude toward his Creator is likely to trend toward being arrogant (ghabid) like Satan instead of being a sincere servant of God (ghibad). As indicated by Petit and Bollaert (2012) based on the research by Glad (2004) and Woodruff (2005), unethical transformational leaders (e.g. Mao Zedong[12], Hitler[13] [14], Stalin[15] [16] and Saddam Hussein[17] [18] [19]) lack humility because they are convinced that their own views or doctrines are infallible though these may be evil, and they fall victim to the Bethsheba syndrome, namely that they do not have to account for their actions. Shura (consultation): through the Qur’anic phrase amruhum shura baynahum (who conduct their affairs through consultation) (42:38) and the Prophet’s (p) habit of seeking and accepting advice, the limits on the exercise of power have been set both by the Qur’an and the Sunnah (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). As Al Buraey points out, shura plays a critical role in administration and management, specifically with respect to decision making; it provides a restraint on administrative power and authority. Unlike the elitist (majority/minority) approaches to decision making, the concept of shura stresses consensus building – a key ingredient of practical wisdom. In Islam, those who are consulted must be competent (ahl-ar-raie) and trustworthy – one of the virtues underlying Muhammad’s (p) character. Accountability focusses on what a person has done with respect to a particular task. It ensures integrity, justice and trustworthiness because the leader’s actions will be gauged by somebody else. In Islam, everyone will have to account for their actions on the Day of Judgment – leaders notwithstanding. This principle is emphasized by the following hadith narrated by ‘Adi bin ‘Amira al Kindi: I heard the Messenger of God (p) say: “Whoso from you is appointed by us to a position of authorityand he conceals from us a needle or something smaller than that, it would be misappropriation (of public funds), and he will (have to) produce (it) on the Day of Judgment.[20]” 8. Contributions of character-centered leadership to management development Based on the above discussion of character-centered leadership, we can now abstract elements of practical wisdom that can be of use to managers in general and to CEOs in particular. Practical wisdom centers on the concept of phronesis discussed by Aristotle Supplied by the NIOC Central Library (Pakaluk, 2005). Practical wisdom can be viewed as a virtue itself; it combines will with skill since it is the moral will (desire) to do the right thing coupled with the moral skill to figure out what the right thing is, and to do so for the right aims (Schwartz and Sharpe, 2010). Based on the above discussion about the character-centered model of the Prophet (p) and Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (2011) analysis of wise leaders, we now suggest how a phronetic leader can develop these skills: Character centered leadership Wise leaders remain focussed on their higher purpose. This higher purpose is what Aristotle calls telos. The higher purpose of Muhammad was to spread the Message of Islam and to guide them toward the good. His Message was neither to compel people to accept the Message nor to use a scorched earth approach against those who rejected his Message. After Makkah was liberated, the Quraish who had tortured, maimed, killed, starved and forced many Muslims into exile expected no mercy from him. Keeping in mind his mission as a Prophet, he behaved benevolently and magnanimously toward his former enemies, saying to them: 1013 . I speak to you in the same words as Yusuf (Joseph) spoke unto his brothers: He said: “You will hear no reproaches today.” (Al-Qur’an 12:92). Go your way, for you are freed ones. Taking revenge would have been contradictory to his higher purpose and nyat. . Wise leaders courageously tackle the most tough and critical problems facing them. Often leaders are confronted with a flood of problems, but must discern which are the tougher and more critical ones to tackle and the right way to tackle them. Some leaders avoid dealing with tough and/or critical problems because of political expediency or economic self-interest. Muhammad (p) was concerned with neither motivation; he tackled the key problems such as idolatry, infanticide, slavery and alcoholism. His approach to different problems was judicious and timely: with respect to idolatry, he dealt with it head on, but with respect to alcoholism, he dealt with it in a more gradual manner – inspired by God. . Wise leaders seek advice from competent and/or experienced people. In figuring out the right way to do the right thing in a particular circumstance, leaders need to recognize that they are not omniscient and that occasionally they lack experience in particular situations. Except in matters of divine revelation, Muhammad (p) sought advice (shura) in situations such as battle strategy where there were more experienced veterans around him. The source of the advice never mattered to him as long he or she was competent or had more experience. Leading in areas where one lacks competence shows a lack of humility and recklessness. . Wise leaders welcome feedback and criticism graciously, and act upon them. Leaders, because of their psychological size, sometimes feel offended at the feedback and criticism they receive from their followers and other stakeholders. Alternately, they may accept others’ comments without intending to follow up. Muhammad (p) when dealing with impatient creditors accepted their harsh criticism of him, and magnanimously refunded them with more than they had lent him[21]. Again, after the Muslims had refused to abide by his command at Hudaybiya, he graciously accepted the advice of Umm Salama (ra) that he set the example and did as she suggested. Supplied by the NIOC Central Library JMD 31,10 . 1014 . . Wise leaders create shared experiences to construct a new paradigm. To impart the message of Islam both in words and deeds, and to nurture a common set of virtues in his early companions, Muhammad as an authentic transformational leader selected Al Arqam’s house to conduct intensive coaching and mentoring in virtues, brotherhood, awareness of world affairs and spiritual upliftment. He also used this process to train his replacement, namely, those who would continue spreading the message after he passed. While CEO at GE, Jack Welch used a similar mentoring process at Crotonville. Wise leaders know when to bend the rules. In Islam, lying is generally forbidden and a major sin. However, in a very few select cases, the Prophet (p) said it is permissible, e.g. putting things right between people[22]. There may be cases when a leader may have to bend the rules to reconcile two parties or make things right for a customer, a patient or even a lender. Wise leaders are grateful. Often as Dennis Koslowski, the former and now convicted CEO of Tyco International pointed out in an interview on the CBS show 60 Minutes[23], CEOs only care about “keeping score,” i.e. competing with one another over who has the biggest toys, etc. Muhammad (p) never kept score, but rather gave away almost everything he owned or received, living so sparingly that sometimes there was no food to be cooked in his house for three days in a row. And yet he used to recite the following prayer (du’a): [y] O God, make me grateful to You, mindful of You, in awe of You, devoted to your obedience, humble, penitent, and ever turning to You in repentance [y][24]. 9. Implications for management development The character-centered model of leadership is virtue centric, and both character and virtues can be taught and can be learned in several ways. First, as Roche (2009) indicates, modeling, a long-standing teaching process since Plato, is a particularly effective way of teaching virtue and thereby teaching character. If you want a follower to learn virtue, have a “virtuous” leader mentor him/her and provide him/her with a moral model. Indeed, Dukerich et al. (1990) found out that followers exhibit higher level of moral reasoning when they emulate leaders who are morally mature. These followers then receive proper acknowledgment and feedback for acting in the right way at the right time. A second approach to learning about character is through “reflective equilibrium,” a process similar to the Aristotelian dialectic. As Hartman (2006) indicates, a well-designed business course can provide students an arena where they can practice in thinking through, reflecting over and discussing different possible scenarios relating to key topics/cases studies so as to obtain a deeper insight into their own moral understanding, and arriving at an “acceptable” set of principles that would allow them to act “out of good character.” One last approach to character (and virtue development) is to use a variant of learning by doing what Japanese style management calls horenso[25]. A Japanese boss asks a young subordinate to take the initiative on a certain project (sometimes a major one), and then proceeds to tell him/her everything he/she did wrong – often without any positive feedback. The subordinate is then asked to fix his/her mistakes and to proceed to the next step. When he/she comes back to his/her boss for feedback, the red pen Supplied by the NIOC Central Library comes out again and this process repeats itself several times until trust is established between the boss and his/her subordinate, and the latter has developed a deep sense of humility. This type of “crucible” event is one of the most effective techniques for character and virtue development. We all have character, but it needs to be developed and nurtured – in the manner Muhammad (p) did with himself and his followers. At the same time, that proponent of practical wisdom, Aristotle, would say that we also need to become virtuous realists. Notes 1. (p) is an abbreviation of “peace be upon him”, an honorific formula that Muslims use when the name of a prophet is mentioned. 2. The Sunnah or Hadith represent “the words, actions, and approvals of the Prophet Muhammad (P)” (Beekun and Badawi, 2005). While Hadiths are not ipsissima verba Dei, they are viewed as “another form of revelation – in meaning – to the Prophet (P).” 3. Al-Albani, Muhammad N. (compiler), Silsilat Al-Ahadeeth Al-Saheehah (in Arabic), Al-Maktab Al-Islaami, Beirut, 1985, Vol. 1, Hadeeth #45, p. 75. Translated by Jamal Badawi. 4. As reported in Sahih Muslim (746). 5. Values, by contrast, are “what an individual wants or desires or ascribes worth to” (Ryan and Bohlin, 1999). 6. The New York Times Editorial (2011) states: “[Jack Welch] earned the nickname ‘Neutron Jack’ for dismissing 100,000 employees in his early days as chief executive. Rather than dwell on the human cost of such downsizing, Mr Welch recalls the challenge with relish in his memoir, Straight From The Gut” (my italics). Jack Welch (2001) in his book, Straight from the Gut, states (pp. 42-3): “I was blunt and candid, and some thought, rude. My language could be coarse and impolitic. [y] During a business discussion, I could get so emotionally involved that I’d stammer out what others might consider outrageous things. [y] I’m the first to admit I could be impulsive in removing people during those early days.” Jack Welch (2001, p. 131) reminisces on the day “in early August 1984 when Fortune magazine put [him] at the top of its list of ‘The Ten Toughest Bosses in America’”. 7. In a New York Times article about Jobs, Nocera (2011) notes, “He could be absolutely brutal in meetings: I watched him eviscerate staff members for their ‘bozo ideas.’” In Leadership in the Media Industry edited by Lucy Kung, Brookey (2006) notes on pp. 107-8, “[Steve Jobs] and his colleague Steve Wozniak were considered the young rebels of the personal computer industry [y], and Jobs was seen as rude, arrogant, and capricious. In 1985, Jobs was driven from the company he helped create.” In Alan Deutschman’s (2001) book, The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, he notes “Steve subjected them to a cruel, quick calculated test. He would [y] ask to see their client list. When they handed it over, he would hardly glance at the printout before he crudely insulted them. ‘This is a lousy client list,’ he would say. [One] accounting partner from Peat Marwick was so incensed by the arrogant, cavalier, cursory treatment that he reacted furiously, looking as though he would throw a knockout punch at Steve.” 8. Narrated by Abu Talhah and reported by Tirmidhi in Mishkat. 9. According to The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, the term jahiliyyah refers to the “pre-Islamic period, or ‘ignorance’ of monotheism and divine law”. 10. (r) means Radhi Allah ‘an, is an acronym used after the names of companions of the Prophet (p), and means “May Allah be pleased with him”; (ra) is the feminine version of that acronym. 11. Umar ibn al Khattab, Sahih al Bukhari, hadith no. 1.1. 12. In Rudolph Rummel’s (1991) book entitled China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900, he states on p. 83 “Mao’s troops executed landlords, ‘local bullies’, Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Character centered leadership 1015 JMD 31,10 1016 usurers, and all sorts of ‘class enemies.’ They often went to excess.” Again on p. 241, Rummel states that, “[lest] there be any doubt on the part of the cadres as to how many of these there were to be eliminated, Mao, in a directive, was very specific: five percent of the members of every organization were ‘elements and should be purged.’ ” Rummer on p. 243 states: “[How] many were killed during this collectivization period? Few estimates are focused on this period alone; most are for the years from 1949 to around 1958, and are in the multi-millions. [y] Based on communist sources, a Hong Kong Study Commission gives a figure of 15,700,000 executed.” 13. Michael Keeley (1995) states on p. 77 that “unless leaders are able to transform everyone and create absolute unanimity of interests (a very special case), transformational leadership produces simply a majority will that represents the interests of the strongest faction. Sometimes this will is on the side of good – as in Gandhi’s case. Sometimes it is on the side of evil – as in Hitler’s.” 14. Gary Beene (2010) states on p. 367 “During the course of the twentieth century, a number of incredibly evil sociopaths rose to power over great nations. Men like Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong [y] and dozens more instigated the democidal slaughter and starvation of 200 million humans.” 15. Valerie Petit and Helen Bollaert (2012) states on p. 267 that “The rule of a tyrant is reliant on fear. The actions of notorious twentieth century tyrants, such as Hitler, Stalin, and Hussein, were punctuated by episodes of extreme cruelty both towards their so-called allies or supporters and towards large sections of the civilian population (Glad, 2004). The tyrant displays a certain number of typical attitudes which then may lead him or her to engage in specific behaviors. Tyrants are convinced of their uniqueness and consider themselves to be above the normal rule of the law (Woodruff, 2005)” (my italics). 16. Sheila M. Puffer and Daniel J. McCarthy (2011) assert on pp. 27-28 that “Traditional Russian leadership style is strong and authoritative (Kets de Vries, 2011) and deeply embedded in the country’s leadership mythology, which embraces the forceful and authoritarian actions of national leaders such as [y] Joseph Stalin in the 1930s to 1950s Soviet terror period [y]. Such leaders are seen as [y] being exempt from the rules [y]” (my italics). 17. Douglas Hunt (2000) states “Future wars between nations are less likely to result from a clash of giants pursuing national objectives than from adventurism, probably of a mediumsized dictator possessed of the instincts of a gambler. The attack by the Argentine military dictatorship on the Falkland Islands was followed eight years later by the attack of Saddam Hussein on Kuwait. [y] Of course the blindness and bloody-mindedness of Saddam Hussein made it difficult, though not quite impossible, for anyone outside Iraq to argue for compromise” (my italics). 18. Askari et al. (2012) state “For the oil-rich economies the effect of corruption on human development is sometimes disguised by oil windfalls used to subsidize generous social welfare programs. To the extent that the PGOE are able to continue to develop in the areas of health, education, infrastructure and employment guarantees during boom periods of oil-driven development, few question the conspicuous wealth accumulation of those in power and the corrupt practices that they may embrace. [y] In post-invasion Iraq, the number and size of Saddam Hussein’s numerous palaces are well documented.” 19. Kenneth Roth (2005) states on p. 148, “Having devoted extensive time and effort to documenting [Saddam Hussein’s] atrocities, we estimate that in the last twenty-five years of Ba’th Party rule, the Iraqi government murdered or ‘disappeared’ some quarter of a million people, if not more. [y] There were times in the past when the killing was so intense that humanitarian intervention would have been justified – for example, during the 1988 Anfal genocide in which the Iraqi government slaughtered some 100,000 kurds.” Supplied by the NIOC Central Library 20. Sahih Muslim, hadith 4514. 21. Narrated by Abu Huraira in Sahih Al Bukhari, 3.780. 22. Narrated by Asma bint Yazid in Al Tirmidhi, 1303. Character centered leadership 23. “Dennis Kozlowski: Prisoner 05A4820,” March 25, 2007. www.cbsnews.com/2100-18560_ 162-2596123.html 1017 24. Fiqh Us Sunnah, 4.133A. 25. http://japaninsight.wordpress.com/tag/japanese-management/ References Abu Laylah, M. (1990), In Pursuit of Virtue: The Moral Theology and Psychology of Ibn Hazm Al Andalusi, Ta-Ha Publishers, London. Al-Qurtubi, A.A.A.-A. (1966), Al-Jaami’ Le-Ahkaam al-Qur’an, Daar Ihyaa’ Al-Turaath Al-Arabi, Beirut. Askari, H., Rehman, S.S. and Arfaa, N. (2012), “Corruption: a view from the Persian Gulf”, Global Economy Journal, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 1-34. Avolio, B.J. and Bass, B.M. (1988), “Transformational leadership, charisma and beyond”, in Hunt, J.G., Baliga, H.R., Dachler, H.P. and Schriesheim, C.A. (Eds), Emerging Leadership Vistas, Heath, Lexington, MA, pp. 29-49. Avolio, B.J. and Bass, B.M. (1991), The Full Range Leadership Devolopment Programs: Basic and Advanced Mannuals, Bass, Avolio & Associates, Binghamton, NY. Bass, B.M. (1985), Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations, Free Press, New York, NY. Bass, B.M. and Steidlmeier, P. (1999), “Ethics, character and authentic transformational leadership behavior”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 181-217. Beekun, R. (2008), “Is Muhammad (p) a transformational leader?”, keynote address to the Conference on Islamic Management and Leadership Ethics, May 20-21, Kuala Lumpur. Beekun, R. and Badawi, J.A. (1999), Leadership: An Islamic Perspective, Amana Publications, Beltsville, MD. Beekun, R. and Badawi, J.A. (2005), “Balancing ethical responsibility among multiple organizational stakeholders: the Islamic perspective”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 60 No. 2, pp. 131-45. Beene, G. (2010), The Seeds we Sow, Kindness that Fed a Hungry World, Sunstone Press, Santa Fe, NM. Brookey, R.A. (2006), “The magician and the iPod: Steve Jobs as industry hero”, in Kung, L. (Ed.), Leadership in the Media Industry, JIBs Research Report Series No. 2006-1, Jonkoping International Business School, Jonkoping, pp. 107-22. Burhan, F.S. (2012), “Wisdom and Islam”, Institute of Arabic and Islamic Studies, available at: www.islamic-study.org/wisdom_%28al-hikmah%29.htm#Flexibility (accessed September 30, 2012) Burns, J.M. (1978), Leadership, Harper & Row, New York, NY. Ciulla, J. (2006), “Ethics: the heart of leadership”, in Maak, T. and Pless, N. (Eds), Responsible Leadership, Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 17-32. Collins, J. (2005), Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap y And Others Don’t, HarperCollins, New York, NY. Deutschman, A. (2001), The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Broadway Books, New York, NY. Dubrin, A. (2012), Leadership: Research Findings, Practice and Skills, 7th ed., Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA. Supplied by the NIOC Central Library JMD 31,10 1018 Dukerich, J.M., Nichols, M.L., Elm, D.R. and Vollrath, D.A. (1990), “Moral reasoning in groups: leaders make a difference”, Human Relations, Vol. 43 No. 5, pp. 473-93. Farling, M., Stone, A.G. and Winston, B.E. (1999), “Servant leadership: setting the stage for empirical research”, The Journal of Leadership Studies, Vol. 6 Nos 1/2, pp. 49-72. Glad, B. (2004), “Tyrannical leadership”, in Goethals, G.R., Sorenson, G.J. and Burns, J.M. (Eds), Encyclopedia of Leadership, Vol. 4, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 1592-7. Graham, J. (1991), “Servant-leadership in organizations: inspirational and moral”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 105-19. Greenleaf, R.K. (1977), Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness, Paulist Press, Mahwah, NJ. Groves, K.S. and LaRocca, M.S. (2011), “Responsible leadership outcomes via stakeholder CSR values: testing a values-centered model of transformational leadership”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 98, pp. 37-55. Halverson, R. (2004), “Accessing, documenting, and communicating practical wisdom: the phronesis of school leadership practice”, American Journal of Education, Vol. 111 No. 1, pp. 90-120. Hartman, E.M. (2006), “Can we teach character? An Aristotelian answer”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 68-81. Howell, J.M. and Avolio, B.M. (1992), “The ethics of charismatic leadership: submission or liberation?”, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 43-52. Humphreys, J.H. (2005), “Contextual implications for transformational and servant leadership: a historical investigation”, Management Decision, Vol. 43 No. 10, pp. 1410-31. Hunt, D. (2000), “The search for peace: a century of peace diplomacy”, European Business Review, Vol. 12 No. 1. Keeley, M. (1995), “The trouble with transformational leadership: towards a federalist ethic for organizations”, Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 67-96. Kouzes, J. and Posner, B. (1995), The Leadership Challenge: How to Get Extraordinary Things Done in Organizations, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. KPMG (2011), “Global anti-bribery and corruption survey 2011”, available at: kpmg.com (accessed September 30, 2012). Kriger, M. and Seng, Y. (2005), “Leadership with inner meaning: a contingency theory of leadership based on the worldviews of five religions”, The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 16 No. 5, pp. 771-806. Leigh, D. (2011), “British firms face bribery blacklist, warns corruption watchdog”, The Guardian, available at: www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/jan/31/british-firms-facebribery-blacklist (accessed September 30, 2012). McMinn, T.F. (2001), “The conceptualization and perception of biblical servant leadership in the southern Baptist convention”, Digital Dissertations No. 3007038, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville, Kentucky. Maak, T. and Pless, N.M. (2006), Responsible Leadership, Routledge, London. Maclntyre, A. (1984), After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 2nd ed., University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IN. Melé, D. (2011), Management Ethics: Placing Ethics at the Core of Good Management, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY. Mintzberg, H. (2004), Managers, not MBA’s, Berett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA. New York Times (2011), “‘Neutron Jack’ exits”, New York Times Editorial, available at: www.nytimes.com/2001/09/09/opinion/neutron-jack-exits.html (accessed September 9, 2001). Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Nocera, J. (2011), “What makes Steve Jobs great”, New York Times, September 9, available at: www.nytimes.com/2011/08/27/opinion/nocera-what-makes-steve-jobs-great.html (accessed September 30, 2012). Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (2011), “The wise leader”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 89 No. 5, pp. 58-67. Pakaluk, M. (2005), Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Petit, V. and Bollaert, H. (2012), “Flying too close to the sun? Hubris among CEOs and how to prevent it”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 108 No. 3, pp. 265-83. Pruzan, P. and Miller, W.C. (2006), “Spirituality as the basis of responsible leaders and responsible companies”, in Maak, T. and Pless, N. (Eds), Responsible Leadership, Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 68-92. Puffer, S.M. and McCarthy, D.J. (2011), “Two decades of Russian business and management research: an institutional theory perspective”, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 21-36. Roche, M.W. (2009), “Should faculty members teach virtues and values?”, Liberal Education, Vol. 95 No. 3, pp. 32-7. Rosenthal, S.B. and Buchholz, R.A. (1995), “Leadership: toward new philosophical foundations”, Business and Professional Ethics Journal, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 25-41. Roth, K. (2005), “War in Iraq: not a humanitarian intervention”, in Wilson, R.A. (Ed.), Human Rights in the “War on Terror”, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Rummel, R.J. (1991), China’s Bloody Century: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ. Ryan, K. and Bohlin, K. (1999), “Values, views or virtues?”, Education Week, Vol. 18 No. 25, pp. 72-3. Safi, L. (1995), “Leadership and subordination: an Islamic perspective”, American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 204-23. Said, E. (1983), The World, the Text, and the Critic, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Schwartz, B. and Sharpe, K. (2010), Practical Wisdom: The Right Way to Do the Right Thing, Riverhead Books, New York, NY. Stone, A.G., Russel, R.F. and Patterson, K. (2004), “Transformational versus servant leadership: a defference in leader focus”, The Leadership & Organization Devolupment Journal, Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 341-61. Tourish, D. and Pinnington, A. (2002), “Transformational leadership, corporate cultism, and the spirituality paradigm: an unholy trinity in the workplace?”, Human Relations, Vol. 55 No. 2, pp. 147-72. Waldman, D. and Galvin, B. (2008), “Alternative perspectives of responsible leadership”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 37 No. 4, pp. 327-41. Welch, J. (2001), Jack: Straight from the Gut, Warner Business Books, New York, NY. Woodruff, P. (2005), “The shape of freedom: democratic leadership in the ancient world”, in Ciulla, J.B., Price, T.L. and Murphy, S.E. (Eds), The Quest for Moral Leaders: Essays on Leadership Ethics, Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton, MA. Further reading Bass, B.M. and Avolio, B.J. (1993), “Transformational leadership: a response to critiques”, in Chemers, M.M. and Ayman, R. (Eds), Leadership Theory and Research: Perspectives and Directions, Free Press, New York, NY, pp. 49-80. Ross, D. (1925), Aristotle: The Nicomachean Ethics, Translated with an Introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Supplied by the NIOC Central Library Character centered leadership 1019 JMD 31,10 Appendix Transformational leadership 1020 Table AI. A comparison of transformational, servant and character-centered leadership models Source of influence Situational context Leader training and skills Unilateral or hierarchical power Servant leadership Character-centered leadership Humility and altruism Spiritual insight with a moral core. Character-centered virtues Relational power; not Either hierarchical or relational self-serving depending on context; not selfserving Nature of Vision; adept at Vision and practice of a Vision is integrative, and focussed charismatic managing human way of life focussed on on inviting others to be God gift resources service conscious and to be of service to mankind Response of Heightened motivation; Emulation of leader’s Followers become servant leaders followers willingness to adopt servant leadership themselves, and exert extra effort vision and goals of model at virtuous self-development; common moral norms and values leader as their own. adopted Common culture may be adopted Moral and personal development of Consequences Leader and/or larger Autonomy and moral followers. Autonomy and search development of of leader goals met; personal influence development of followers; enhancement for knowledge encouraged. Enhancement of common good of common good followers Sources: Adapted and modified from Graham (1991) and Tourish and Pinnington (2002) About the author Rafik I. Beekun (PhD, the University of Texas at Austin) is Professor of Management and Strategy in the Managerial Sciences Department and Co-Director, Center for Corporate Governance and Business Ethics at the University of Nevada, Reno. His current research focuses on business ethics, leadership, national cultures and the link between management and spirituality. He has published in such journals as the Journal of Applied Psychology, Human Relations, Journal of Management, Journal of Business Ethics and Decision Sciences. This paper is based partly on his forthcoming book, Moral Character: Leadership Lessons from Islam. Rafik I. Beekun can be contacted at: rafikb@unr.edu To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints Supplied by the NIOC Central Library