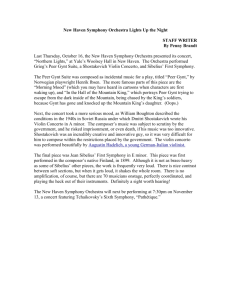

Festive Overture, Op. 96 Dmitri Shostakovich Born

advertisement

Festive Overture, Op. 96 Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906, in St. Petersburg, Russia Died August 9, 1975, in Moscow, Russia In 1954, the year Dmitri Shostakovich received the high government honor as The People’s Artist, he produced his Festive Overture. Here is a light-hearted work filled with bright melodies supported by standard harmonies: a perfect recipe for the Soviet aesthetic that demanded “simple tunes, simple harmony, and simple tales on the good fortune of life in the Soviet idyll.” Brilliant trumpet and horn calls introduce the Overture’s high stepping tunes and energy. Growing in momentum, the Overture unveils a second theme introduced by cellos and horns in a virtuosic presto. A recall of the opening returns at the end, but it is the vivacious presto that steals the show and brings Op. 96 to its jolly conclusion. Jack Everly conducted the orchestra’s last performances of Festive Overture in March 2009. Concerto No. 2 in F Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin Born March 1, 1810, in the village of Zelazowa Wola near Sochaczew, in the Duchy of Warsaw Died October 17, 1849, in Paris, France Frédéric Chopin’s two piano concertos are youthful works: the so-called second (in F Minor) written when he was 19, and the so-called first (in E Minor) when he was 20. Neither marked new developments in concerto format or form; both were written as vehicles for pianistic display and beauty, without significant orchestral writing. For the composer, the orchestra was more or less a master of ceremonies, a lesser partner, but necessary for the concerto format. His live-in, the author George Sand (Aurore Dudevant), wrote, “Invention came to his piano: sudden, complete, and sublime.” The F Minor Piano Concerto premiered to great acclaim in the first public concert of Chopin’s own music on March 17, 1830, in Warsaw. In Paris, on February 26, 1832 (one year after his arrival in 1831), Chopin wowed a distinguished audience including Felix Mendelssohn and Franz Liszt, with another dazzling performance of Op. 21. The incipient love affair between the young Chopin and Parisians reached new intensity. But Parisians were a fickle lot; in about 10 years his star waned, and he was more or less discarded as passé! Op. 21 begins with a double exposition, first by orchestra and then by piano, sharing the two major themes. The first is a maestoso declamation; the second more lyrical, is introduced by the oboe. A relatively small development follows, which leaves out any reference to the second idea, focusing heavily instead on the first. This second idea, however, receives great attention in the recapitulation. Chopin’s wild love for Constantia Gladkowska inspired his tender second movement. In 1829, he had written to a friend, Titus Woyciechowski, “I have – perhaps to my own misfortune – already found my ideal whom I worship faithfully and sincerely; I have not yet exchanged a syllable with her of whom I dream every night. While my thoughts were with her, I composed the Adagio of my concerto.” The piano stars in singing the lyrical theme with orchestral support held to a minimum. Herein is the Chopin of nocturnes, of bel canto for the keyboard. After the premiere, Franz Liszt commented, “Passages of surprising grandeur may be found in the Adagio of the Second Concerto for which he showed a decided preference and which he liked to repeat frequently... . The whole of this piece is of a perfection almost ideal; its expression now radiant with light, now full of tender pathos.” Chopin unleashes the reins for his last movement with jolly, dance-like informal music. Both forces take turns in all the merriment. The music runs unabashed to a coda featuring a horn solo. At age 19, the composer clearly was finding his pianistic voice, but only one other piano concerto would emerge. Emanuel Ax was soloist under the direction of Keri-Lynn Wilson for the orchestra’s last performances of Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in June 2002. Symphony No. 5 in E Minor, Op. 64 Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Born May 7, 1840, Votkinsky, Russia Died November 6, 1893, in St. Petersburg, Russia Ten years separate Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s fourth and fifth symphonies. In August 1888, when he did complete the fifth, he was uncertain about its stature and self-deprecating. He wrote to his patroness, Mme. Von Meck, saying, “It is obvious to me that the ovations I received (for the fifth) were promoted more by my earlier work and that the symphony itself did not really please the audience. Am I really played out, as they say?” He continued in the same mood saying, “I have come to the conclusion that it is a failure. There is something repellent in it, some overexaggerated color, some insincerity of fabrication, which the public instinctively recognizes.” Tchaikovsky had conducted the premiere in St. Petersburg on November 17. Although the audience was enthused, the first critics affirmed his inner doubts. Some did feel that the work was “unworthy” of Tchaikovsky. But later assessments have been far more complimentary and receptive. As the years passed, the beauty and power of the fifth symphony have been heralded and acclaimed by critics and audiences alike. The fifth symphony is built around an obsessive repeating motif (small musical theme or idea), which was identified as the “Fate Motif.” The motif appears in assorted guises in all the movements. Edward Downs observed, “The symphony is unified by a striking theme, which reappears so dramatically in all four movements that a ‘plot’ of some sort is strongly suggested.” At every chance, even at brighter moments, this stern “Fate Motive” intrudes to spoil the fun or temper the optimism. Tchaikovsky’s introspective, despairing nature was a natural fit for the idea of fateful controls and intrusion. For years, Tchaikovsky had been preoccupied with such notions, and he wrote to the Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich during the creation of the fifth symphony, “Introduction. Total submission before Fate – or what is the same thing, the inscrutable designs of Providence. Allegro. 1. Murmurs, doubts, laments reproaches … . 2. Shall I cast myself into the embrace of Faith?” The introduction of the first movement places the foreboding Fate symbol in the low range of clarinets and bassoons over a delicate string accompaniment. After this small introduction, clarinets and bassoons present the first theme, derived from a Polish folksong, in a bright allegro setting. Strings follow with a lyrical melody marked molto cantabile ed espressivo, which comprises the second theme. A long development and recapitulation complete the first movement structure. The slow movement spotlights a beautiful melody sung by the first horn. A second horn eventually joins, enriching and thickening the texture. A subsidiary melody spins from the oboe, and then the “Fate Motif” screams intrusively from the trumpets. Sweet substantive themes return only to be elbowed aside by trombones insisting on the “Fate Motif” statement. The third movement features a luxuriant waltz presented by the first violins. Tchaikovsky had heard the tune in Florence years before and now felt that he had found just the right spot for it. Again, in the midst of this delight, the “Fate Motif” appears, insisting on its controlling presence and power. The finale comes to grips with the “Fate Motif” intruder in its opening, and then proceeds to reach two powerful climaxes. After a slow beginning, the musical mood gives way to exuberance. Winds dance and fall over each other, and the atmosphere is positive. Two other themes emerge, one derived from the first theme of the first movement, and then the symphony concludes with trumpets stating the “Fate Motif” in a triumphant stance. The four concluding chords, however, strongly suggest that defeat is inevitable. As one Russian observed, “If Beethoven’s fifth is Fate knocking at the door, Tchaikovsky’s fifth is Fate trying to get out.” The Orchestra’s last performances of Symphony No. 5 were conducted by Vasily Petrenko in October 2006.