alonso_culpa (dragged) 2

advertisement

12/29/13

Page 4

FACETS OF LIABILITY

IN ANCIENT LEGAL THEORY

AND PRACTICE

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SEMINAR

HELD IN WARSAW 17–19 FEBRUARY 2011

EDITED BY

JAKUB URBANIK

O F

T H E J O U R N A L

Supplement XIX

10:05 PM

CULPA

J

U R I S T I C

P

A P Y R O L O G Y

SUPPL_XVIII_CULPA_str

WARSAW 2012

Culpa. Facets of Liability in Ancient Legal Theory and Practice

Proceedings of the Seminar Held in Warsaw 17–19 February 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cosimo Cascione & Carla Masi Doria

Prefazione . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii

Alessandro Adamo

Di alcune ipotesi di colpa

nella legislazione criminale del Codice Teodosiano . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

José Luis Alonso

Fault, strict liability and risk in the law of the papyri . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Zuzanna Benincasa

Pro portionibus exercitionis conveniuntur.

Sul problema della responsabilità di plures exercitores

qui per se navem exerceant . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

Stanisław Kordasiewicz

La colpa e la responsabilità del tutore . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

Alessandro Manni

Noxae datio del cadavere e responsabilità . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

Giovanna Daniela Merola

Accertamento della responsabilità e mantenimento dell’ordine:

il ruolo del centurione . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

Natale Rampazzo

Note sulla responsabilità del giudice e dell’arbitro nel processo romano . . . 181

VI

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Paulina ŚwiĘcicka

La colpa aquiliana e il ragionamento dei giuristi romani.

Alcune riflessioni sulla struttura dell’argomentazione e delle regole

di preferenza nel discorso dogmatico giurisprudenziale

in tema di danneggiamento . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

Anna Tarwacka

‘Censorial stigma’ and the problem of guilt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

Fabiana Tuccillo

Alcune riflessioni sulla responsabilità del magistrato e dell’adsessor.

Dolus, diligentia, culpa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 257

Jakub Urbanik

Dilligent carpenters in Dioscoros’ papyri and the Justinianic (?)

standard of diligence. On P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158 and 67159 . . . . . . . . . 273

Culpa. Facets of Liability in Ancient Legal Theory and Practice

Proceedings of the Seminar Held in Warsaw 17–19 February 2011, pp. 273–296

Jakub Urbanik

DILIGENT CARPENTERS IN DIOSKOROS’ PAPYRI

AND THE JUSTINIANIC (?) STANDARD OF DILIGENCE*

ON P. CAIRO MASP. II 67158 AND 67159

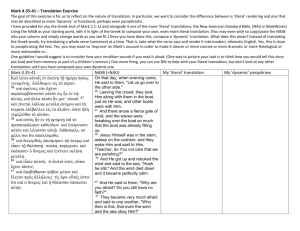

1. CULPA-BASED LIABILITY IN THE LATE PAPYRI

T

he most natural first move before even attempting to discuss the

problem of liability based in negligence in the late Byzantine1 papyri

is to check what Rafał Taubenschlag would have to say in the subject in

his standard reference book. And in fact, the scholar, presenting the

problem of culpa-liability, makes an explicit reference to two papyri

found among the papers of Dioskoros,2 the notorious poet and lawyer

* I owe thanks for all the useful comments to Józef Mélèze Modrzejewski and José

Luis Alonso, who have read the earlier drafts of the paper.

1

I am using the term ‘Byzantine’ as an equivalent of ‘Late antique’, in reference to the

papyri in accordance to the well-established papyrological practice which terms post-Diocletian Egypt as ‘Byzantine’.

2

It would be unnecessary to quote all the literature on Dioscoros, suffice it to recall his

classic biography by Leslie MacCoull, Dioscorus of Aphrodito, Berkeley – Los Angeles –

London 1988 for an overview of his life, and for the most recent update on the scholarship and the literature a collection of studies edited by Jean-Luc Fournet, Les archives de

Dioscore d’Aphrodité cent ans après leur découverte. Histoire et culture dans l’Égypte byzantine

(Études d’archéologie et d’histoire ancienne), Paris 2008.

274

JAKUB URBANIK

from Aphrodite, the man on whose legal oeuvre I have been conducting

my research in the recent years. There are two contracts of partnership

between artisans, P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158 and ii 67159 (= 67160). Taubenschlag states that these ‘[t]wo Byzantine contracts of artisan-partnership

were evidently drawn up under the influence of Justinian’s legislation …

[T]he parties exceed the provisions of Justinian’s legislation establishing

culpa omnis as the standard of ca{s}<r>e’.3 Both documents were executed

during the Antinoopolitan period of our scholastikos, in the course of the

year 568 and bear far-reaching similarities. What I would be mostly interested here is, obviously, the standard of the parties’ liability and its possible origin in the legislative effort of the great codifier. These two specimens, however, are worth a more in-depth look not only because they

seem to portrait rather curious realities of the legal life of the sixth century Antinoopolis. They also constitute examples of extremely rare

occurrences of partnerships in the papyri.4 To neither of them the scholarship has devoted the attention they definitely deserve, to my knowledge neither of them has also been translated to any modern languages.5

3

R. Taubenschlag, The Law of Greco-Roman Egypt in the Light of the Papyri, Warsaw

1955 (2 ed.), p. 393.

4

For the – list of the documents – see Orsolina Montevecchi, La papirologia, Milano

1988 (2 ed.) p. 225.

5

In the earlier literature they have been only briefly described, none of the authors has

devoted an in-depth analysis. See, hastily, H. Lewald, rev. of P. Cairo Masp. i–ii, ZRG RA

33 (1912), pp. 620–628, at p. 622; a more detailed description: R. Taubenschlag, ‘Societas

negotiationis im Rechte der Papyri’, ZRG RA 52 (1932), pp. 64–77, at pp. 76–77 (the author

seems to have drawn a bit too far-reaching conclusions, arguments bulit upon a comparison of all, very scarce, documents registering partnerships in the Greek papyri, especially

these executed under Ptolemies and Byzantine ones, lead to dubious results); see also

A. Steinwenter, ‘Aus dem Gesellschaftsrecht der Papyri’, [in:] Studi Riccobono i, Palermo

1936, pp. 485–504 at 488–489. This article still remains a useful introduction to the problem of partnership in the papyri, providing a general overview of the issue, terminology

and the form of the documents. V. Arangio Ruiz in his Fontes Iuris Romani Anteiustiniani (hereinafter FIRA) iii. Negotia provided P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158 with a Latin translation and with a brief commentary (nº 158).

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

275

2. PARTNERSHIPS

OF FINE-CARPENTERS FROM ANTINOOPOLIS

Let me start from the earlier one, P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158, probably dated

to 28 April 568.6 Unfortunately it lacks a strip 10–15 letters wide on the

left margin, hence its interpretation is based on a reconstruction suggested by the editor. Its content merits a special attention for the particular social circumstances in which it was executed. As no translation to

modern languages has been so far made public I shall first attempt at providing the Reader with an English interpretation of the text and then

proceed to clarify its contents.

a) P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158, 28 April/May 568

?† χµγ\

[☧ βασιλείας καὶ ὑπατ]είας τοῦ θ[ει]οτάτου ἡµ[ῶν] δεσπότο[υ]

Φλαυΐου ᾿Ϊ[ο]υστίνο(υ) τοῦ αἰωνίο(υ) Αὐγούστου Αὐτοκράτορος

ἔτους

[τρίτου, Παχὼν τρ]ί1τῃ ἀρξοµένης δευτέ[ρα]ς ἐπινεµ[ή]σεως κατὰ2

θεῖον νεῦµα. ἐν Ἀντινόο(υ) πόλει τῇ λ[α]µπροτάτ[ῃ].

[ταύτην ποιοῦ]ν2ται καὶ τίθενται πρὸς ἀλλήλους τ[ὴ]ν πα[ρ]οῦσαν1

ἁ2πλῆν ἔγγραφον κοινὴν ὁµολογίαν κατὰ κοι1[νὴ]ν

4 [γνώµην καὶ ἄν]ευ π2α2ντὸς δ2όλου καὶ φόβ1ο(υ) καὶ βίας καὶ ἀνάγ3κης καὶ

ἀπάτης καὶ οἵας δήποτε συναρπαγῆς τε καὶ [π]ερι[γραφῆς, ἐφ’ αἷς π]ε1ρ3ιέχει δι[α]στολα2ῖ1ς ἁπάσα2ι1[ς] ἐ2πὶ τοῖς ἑ[ξ]ῆς

δ2[η]λου[µ]ένοις συµφώνοις, ἐκ µὲν ἑνὸς µέρους Αὐρήλ[ιο]ς

[Ψόϊς υἱὸς Ἰσακίο(υ)], ἐκ µη2τρὸς Μαρίας, τέκτων λεπτουργός,

ὁρµώµενος ἀπὸ ταύτης τῆς λ[α]µπρᾶς Ἀντινοέων πόλεως,

[ἐκ δὲ θατέρου µέρο]υς Αὐρήλιος ᾿Ϊωσῆφις ὁ καὶ Πεκῦσις, υϊὸς

Παύλου, µετὰ συνεστώσης καὶ συνευδοκούσης καὶ

συνπει[θ]οµέ(νης)

6

The name of the month, Pachon, has been reconstructed in the left-margin lacuna.

As R. S. Bagnall & K. A. Worp, Chronological Systems in Byzantine Egypt, Leiden 2004 (2 ed.),

p. 101, n. 1 observe, Pauni is also possible, thus giving us a date one month posterior:

28 May 568.

276

JAKUB URBANIK

8 [αὐτῷ τῆς αὐτοῦ γαµετ]ῆς Αὐρηλ2ίας Τικολλο(ύ)θου, θυγατρὸς

Ὡρο2υ2ωγχίο(υ), ἐκ µητρὸς Παυλίνης, γ[α]µετῆς συµβίο(υ)

αὐτο(ῦ), τῆς κ(αὶ) συναινο(ύ)σης

[αὐτῷ ἐπὶ ταύτῃ τῇ αὐ]το(ῦ) ὁµολογίᾳ ἐγγράφῳ ἀκολο(ύ)θως τῇ

δ[υ]νά2[µ]ει αὐτῆς ἐκ παντὸς τρόπο(υ). καὶ ὁµολογο(ῦ)σιν

ἀλλήλοις οἱ ἀφ’ ἑκατέρο(υ)

[µέρους τὰ ὑποτετ]αγµένα χ(αί)ρ(ειν). ὁ[µ]ολογοῦµεν ἡµεῖς οἱ

προγεγραµµένοι Ψόϊς ᾿Ϊσακίο(υ) λεπτουργὸς καὶ ἀνὴ2ρ τυγχάνων

τῆς θυγατρὸς ᾿Ϊωσ2[η]φίο(υ)

[καὶ Τικολλο(ύ)θου τῶ]ν συνκοινωνῶν µο(υ) τῇ το2(ῦ) Θεοῦ προνοίᾳ κα2ὶ1

συµπραγµατευτῶν µο(υ), κα(ὶ ἐγ)ὼ α2ὐτὸς ᾿Ϊωσῆφις ὁ προρηθεί[ς],

12 [µετὰ συνεστώσης τῆ]ς συνο(ύ)σης καὶ συναινούσης µοι γαµετῆς εἰς

ταύτην τὴν κοινὴν καὶ ἔγγρ3αφον ἀπαράβατον ὁµολογία2ν2,

[ἑκουσίως τε καὶ] κοινῇ γνώµῃ καὶ ἀδόλῳ3 πρ3ο2αιρέσ[ει],

συνεργάζασθαι ἀλλήλοις εἰς τὴν κοινὴν ἡµῶν πραγµατείαν2, καὶ

[πάντων τῶν συµβη]σοµένων [ἡ]µῖν ἐµποι1ῆ2σ2αι ὠνίων διάπρασιν κατὰ

κοινὴν πειθαρχίαν καὶ βουλὴν καὶ συναίνεσιν ποιήσασ?θαι\,

[δίχα πάσης ῥᾳδ]ιουργίας κ[αὶ] µ1έµ[ψ]εως κ[αὶ] κ2α[τ]α

καταφρονήσεως καὶ οἵας δήποτε ὀκνηρία[ς], ἐνδείξασθαι ?τε\

ἀλλήλοις πρόθεσιν µετὰ

16 [προαιρέσεως(?)] συγκάµνοντες, καὶ συµπνεεῖν ὁµοδυµαδὸν ὡς ἐκ

µιᾶς ψυχῆς καὶ θάρσο(υ)ς ϊσχύος καµατερῶν ἐξ ἴσου

[πάντων τῶν ἐρ]γαστηριακῶν καὶ πραγµατευτῶν ταύτης τῆς πόλεως

ἡµῶν Ἀντινόο(υ), κα[ὶ] ϋπακούειν ἀλλήλοις ἐν πᾶσι

[καλοῖς καὶ ὠφ]ελείµοις ἔργοις καὶ λόγοις, χωρὶς ἀντιλογίας οἵας

δήποτε καὶ ἀντιπαθείας καὶ ὕ!!ϋ!!βρεως, καὶ τὸ εἰσοδευόµενον

[ἡµῖν ἀπὸ παν]τὸς κοινω2φ3ελοῦς ἡµῶν ἐκ τῆς ἐργασίας κέρδος ?ἐξ\

οἵου δήποτε πράγµατος καὶ ἐργοχείρο(υ) εἶναι ἐξ ϊσοµοιρί?ας\

20 [ἡµῖν κατὰ τὸ ἥ]µ1ισυ2 µέρος, µετὰ τὴν ἀποπλήρωσιν τῆς µεταξὺ ἡµῶν

ο(ὔ)σης µέντοι προχρείας, κα2ὶ1 τήν, ὅπερ ὡσαύτως ἀπείη, ἐσοµένην1

[ζηµίαν ἐξ ὁµοίο(υ) τ]ρόπο(υ) ἐξ ἴ̈σης ἡµίσειας µοίρας

ἀπολογήσασθαι. ο[ὐ]δὲν ἧτ’τον, εἰ ἐθελήσοιµεν ἀποστῆ[ν]αι τῆς

κοινῆς µετ’ ἀλλήλων ἐργασίας,

[ἑτοίµως ἔχειν τ]ὰ δάνια το(ῦ) ὄπιθεν χρόνο(υ), [τ]ὰ γενάµενα ἡµῖν

κοινῶς πραγµατευοµένοις, ἐπιγνῶναι κατὰ τὸ αὐτὸ ἥµισυ µέρος

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

277

[ἐξ ἰσοµοιρίας,] ἐφ’ ὅ τε ἐν µιᾷ ἐργασίᾳ καὶ εὐζωΐᾳ κοινῇ µετ’

ἀλλήλων δ2ιήξαµεν τὸν κατ’ ἐκείνο2(υ) καιρο(ῦ) χρόνον: καὶ οὐ

δύνατόν τινι

24 [ἡµῶν περὶ τούτ]ο(υ) ἀµφιβάλλειν ποτέ, µάλιστα ?ἐµε\ Ψόϊν τὸν ϋµ[έτ]ερον γαµβρόν, ἐπὶ προσδοκία[ς] ἔχοντα, εἰ τῷ θεῷ δόξειεν εἶναι,

[τόν τε κληρονό]µον καὶ διάδοχ(ον) ϋµῶν λήµψεως καὶ δόσεως ϋπὲρ3

ϋµῶν γενέσθαι, µετὰ τὴν ϋµῶν1 ἀποβίωσιν. καὶ σὺν Θεῷ ἐν µιᾷ

[ἐργασίᾳ γενησόµ]εθα καὶ βίωσει µετ’ ἀλλήλων µεθ’ ὁµονοίας ἔργου,

ἀπὸ τῆς σήµερον καὶ προγ[εγ]ραµµέ(νης) ἡµέρας, ἥτις ἐστὶν

τρίτη το(ῦ)

[Παχὼν µηνὸς τῆς] ἀρξοµένης κατ’ Αἰγυπτίους δευτέρας ἐπινεµήσεω2ς,

ἐπὶ τὸν ἀεὶ ἑξῆς ἅπαντα πρ3οσελαύνοντα χρόνον, ἀµέµπτως κ(αὶ)

28 [ἀκαταγνώστως. καὶ] εἰς ἀσφάλειαν πά1ν1των1 τ1ῶ2ν1 προδιωµολογηθέντων παρ’ ἡ2[µ]ῶν, ἐπωµ1οσάµεθα τὸν φ3ρικωδέστατο[ν] ὅρκον ἐν

οὐδενὶ µὴ παραβῆναι, καὶ πρόστιµον

[κατὰ τοῦ παρ]αβαίνειν ἐπιχειρή[σον]τος ἐπικεῖσθαι χρυσο(ῦ)

νοµισµατί[ω]ν ἓξ εὐστάθµων καταβλη2θ2ῆναι, ὥστε ?τα[ύτ]α\

τ[ῷ] ἐµµένοντι καὶ στοιχοῦντι µέρει ἐξ ἐπερωτήσεω?ς\

[δοθῆναι, µετὰ] κ2[(αὶ)] τ1ο(ῦ) αὐτὸν τὸν παρα2βάτην ἄκοντα ἐµµεῖναι τοῖς

ἐγγεγραµµ(ένοις) [συ]µ1φώνοις: ἐφ’ οἷς ἐρωτηθέν2τε2 ς παρ’ ἀλλήλ[ων]

καὶ ἀλλήλο(υ)ς ἐπερωτήσαἐπερωτήσαντες ταύθ’ οὕτως ἔχειν δώσειν

[φυλάττειν ὡµολογ]ήσαµεν, ϋποθέµενο[ι] δὲ καὶ ἀλλήλοις εἰς ταῦτα

πάντα τά τε νῦν ὄ2ν2[τα] ἡ2µῖν καὶ ἐσ2[ό]µενα πράγµατ1α, γεν1ικῶς

καὶ ϊδικῶς, ἐ1[ν]εχύρο(υ) λόγῳ καὶ ὑ1ποθήκ(ης) δικαίῳ καθάπερ ἐκ

δίκης ☧

9. BL vii 35: ἐν original ed.; corr. from εγγραφο | 13. l. συνεργάζεσθαι | 15. l. ἐνδέξασθαί. | 15. BL i 448: µετα[λαβεῖν τὸ ἥµι(?)]συ κάµνοντες original ed. | 16. l. συµννεει.

| 16. corr. from ὁµοθυµατὸν, l. ὁµοθυµαδὸν | l. καµατηρῶν | 18 l. ὠφ]ελίµοις. | 22. BL

iii 35: ἔχοµεν original ed. | L. δάνεια | 24. BL i 448: [τοῦτ]ο original ed. | 28. l. προδιοµολογηθέντων | 29. subsequent ed.: ἐπιχειρή[σαν]τος original ed.

ll. 1–2: † χµγ During the reign and consulship of our most pious Lord,

Flavius Iustinus, the eternal August and Imperator, year third, on the

278

JAKUB URBANIK

third of Pachon (?) of the second indiction (year), commenced according

to the divine (i.e. imperial)7 will, in the most splendid city of Antinoe.

ll. 3–10: Aurelios Psois, son of Isakios, his mother being Maria, fine-carpenter,8 coming from the same splendid city of Antinoe on one side, and

on the other side, Aurelios Iosephis also known as Pekysis, son of Paulos

in assistance of jointly consenting and co-agreeing his consort, Aurelia

Tikollouthos, daughter of Horounchios, of mother Pauline, his weddedconsort, who is agreeing with him in regard to his written agreement in

accordance with her will in all places. make and prepare for one another

out of their common will and without any kind of fraud and fear and force

and constraint and deceit and whatever kind of treachery and robbery and

circumvention, this present common agreement written in a single copy

under the articles (that it) contains and according the below apparent

common agreement. And they agree what is below appended from either

of them. Greeting.

ll. 11–20: We, I, the above-written Psois (son) of Isakios fine carpenter

and who also happens to be the husband of the daughter of Iosephios and

Tikollouthos, my partners and associates by God’s will, and I, Iosephis,

the above-said, with assistance of my wife joining with me and agreeing

with me to this common and written and unalterable agreement, agree

voluntarily and of joint will and non-fraudulent conviction, that we collaborate with one another to the joint our business and that the sale of all

merchandise produced that may come to us (from this agreement) shall be

made according to joint management and will and approval without any

laziness or blame or negligence or whatever dilly-dallying, and that we will

involve as much as possible commitment and conduct, straining ourselves

together and that we will breath together with one accord, as if we had

one soul and courage (and) might, (providing work-labour) equal to the

one of all the craftsmen and workmen of this our city of Antinoe, and to

comply with one another in every proper and beneficial action and word,

without any protest whatsoever or opposition or outrage, and that the

work-profit collected for us from everything of common utility of all kinds

of matters and work of our hands shall be equally divided between us, halfto-half, having deducted in full all the former debts between us, and similarly any future loss – which may not happen! – will be borne in equal halfshares.

ll. 20–25: And should we wish to abandon this joint labour-partnership

between us we shall immediately admit the loans of the preceeding time,

7

Cf. Bagnall & Worp, Chronological Systems (cit. n. 6), p. 34.

8

Cf. Dioc. Ed. vii 3. Cf. S. Laufer, Diokletian’s Preisedikt, Berlin 1971, comm. ad h.l. with lit.

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

279

which came into existence between us because of the joint undertakings,

in the same half-parts, that is equal shares, for the period of time in which

we have led one labour-community and harmonious joint-life. And it shall

not be allowed to neither of us to bring any type of suit because of these

matters, and especially to me, Psoi, your son-in-law, who has got the

expectation, should it please God, of being taken and of appointment by

you still in life to (be) your heir and successor after the completion of your

life. And so we shall be, with God’s will, in one labour-partnership and living of harmonious work, from this, the above-written day, that is the third

of Pachon of the coming second Egyptian indiction, for ever, all time

coming afterwards, blamelessly and not giving reason to be brought to

court.

ll. 26–31: And to secure all points conceded on both sides beforehand

by us we are swearing the awe-inspiring oath not to transgress in anything,

and that a fine of six coins of gold of fine weight should be paid by the

party in breach to the party abiding and keeping the agreement in virtue

of a stipulation, and because of it, the same transgressor, (even) an involuntary one, will abide to the above-written terms, on which both of us

have agreed, being formally asked to do so by each other, and having stipulated that they shall have and give and guard all these, and we are mortgaging to each other all the matters that we have now and shall have, both

generally and singularly by virtue of pledge and right of hypothec, executable without a trial.

The parties, Aurelios Psois, son of Isakios and Aurelios Iosephis also

known as Pekysis, son of Paulos together with his wife Aurelia Tikollouthos, daughter of Horounchios, fine carpenters, make a joint agreement of partnership.9 They will work together in their trade and divide

9

It is not my purpose in this place to analyse in detail the dogmatic foundations of the

contract of societas in Roman law, I will only address some points as to the standard liability of the partners towards the end of this paper. For the most general overview of this

legal figure see R. Zimmerman, The Law of Obligations. The Roman Foundations of the Civilian Tradition, Oxford 1996 (2 ed.), pp. 451–467 and two excellent recent books on the subject. 1. F. S. Meissel, Societas. Struktur und Typenvielfalt des römischen Gesellschaftsvertrages,

Frankfurt a/M 2004, passim, esp. pp. 131–204, for the so-called societas negotiationis alicuius

and societas unius rei which would correspond to our cases here (the author very soundly

points out that the Roman jurists did not aim at theoretical and terminological diversifications, and so the ultimate distinction between various types of societas cannot be reasonable based on our, somewhat nominally blurry, sources); for a brief commentary on our

280

JAKUB URBANIK

the proceeds from the sale of the produced objects. The loss is to be similarly borne in equal shares. Two circumstances catch our attention. The

first, and the most outstanding, is the standard of conduct to which the

parties undertake to abide to. They stipulate to act with the diligence

typical for all the craftsmen of the city of Antinoopolis: ἐξ ἴσου | [πάντων

τῶν ἐρ]γαστηριακῶν καὶ πραγµατευτῶν ταύτης τῆς πόλεως ἡµῶν Ἀντινόο(υ) – ‘equal to the one of all the craftsmen and workmen of this our

city of Antinoe’. This criterion could be understood in the slightly

anachronic terms of the Romanistic scholarship as culpa levis in abstracto:

the standarised type of negligence/diligence-based type of conduct which

would be proper to an abstract representative of the given class of contactor. In most cases this pattern is set by the behaviour typical for a

good and diligent father of family (bonus et diligens pater familias),10

but sometimes the standard seems to be fixed at an example typical for a

given situation – like ‘a (diligent craftsman’ in D. 19.2.9.5 (Ulpianus 32 ed.),

analysed below. I shall return to this point in a moment (infra, pp. 292–294).

The second interesting feature of our document is its supposed aim.

It is seemingly a contract of partnership of artisans. Psois, however, is the

son-in-law of the other party, Iosephis and Tikollouthos. Obviously there

is nothing awkard or out-of-order in making business within a blood or

political family. Let us notice that Psois expresses his expectation to

become the heir to the estate of his parents-in-law. This estate, moreover, seems to be treated as a joint matrimonial property, and that is possibly why, the wife appears alongside her husband in the terms of the

agreement. It could be argued, therefore, that the societas-agreement here

operates as a particular matrimonial settlement between the parents-inlaw and the husband of their daughter (who, interestingly, is not admitted to the bond at all). It may be yet another ingenious example of how

to manage property after marriage and how to secure proper care over the

papyri see pp. 152–153. 2. G. Santucci, Il socio d’opera in diritto romano. Conferimenti e responsabilità, Padova 1997, who, however, does not really engage with the sources of the legal

practice, apart from a Dacian triptych, FIRA iii nº 157 (on which cf. infra, pp. 291–292).

10

See, e.g. Zimmerman, Law (cit. n. 9), pp. 210–211 in respect to depositum.

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

281

family estate in a different way than a classical standard dowry agreement.11

The whole agreement is concluded by a stipulation clause, typical for

all types of contracts and secured by a general mortgage.

b) P. Cairo Masp. ii 67159, 16 December 568

Before I discuss further the liability model assumed by the carpenters, let

me present the other case, P. Cairo Masp. ii 67159. It has been preserved

in two copies,12 none written by Dioskoros himself. This circumstance

opens an interesting question about the reason of their existance in his

archives. Slightly more correct P. Cair. Masp. ii 67160 may have been a

second, perhaps the final, draft of the agreement. Again we are faced with

a partnership of carpenters.

☧ βασιλείας [κ]αὶ [ὑπ]ατεί[ας] τ2οῦ θειοτάτ[ου ἡµ]ῶν δεσπότου

Φλαυΐου

Ἰουσ[τί]νου τοῦ αἰω2[νίου] Α2ὐγούστου Αὐτοκράτορος ἔτους τετάρτου,

Χοι[ὰ]κ εἰκάς δευ[τέ]ρ1ας ἰνδ(ικτίονος). ἐν Ἀντι(νόου) πόλει τῇ

λαµπροτάτῃ.

4 ☧ ταύτην τίθεντα[ι] καὶ ποιοῦνται πρὸς ἑαυτοὺς τὴν ἀντισύγγραφο?ν\

κοινὴν δισσὴν ὁµολογίαν, ἐπὶ τοῖς ἑξῆς δηλουµένοις συµφώνοις

ἐφ’ αἷς περιέχει διαστολαῖς ἁπάσαις: ἐκ µὲν τοῦ ἑνὸς µέρους Αὐρήλ(ιος)

Δανιῆλις ἐκ πατρὸ2ς Ἰω2σηφίου, ἐκ µητρὸς Θέκλας, λεπτουργὸς

11

Another example of such invention to be found among the papers of Dioskoros is a

set of documents P. Michael. 42a – a mortgage by which the groom and his parents convey

to the bride 10 arurae of land to secure repayment of the latter’s dowry – and P. Michael.

42b by which the bride leases the same land back to her political family for the rent

equalling the annual tax on the estate. See further my ‘Marriage and divorce in the late

antique legal practice and legislation’ [in:] Esperanza Osaba (ed.), Derecho, cultura y sociedad

en la Antigüedad Tardía, Bilbao 2013 (in print).

12

Heidelberger Gesammtverzeichnis der Papyri (and after it also the website Papyri Info

<<www.papyri. info>>), wrongly states that P. Cairo Masp. iii 67315 recto is a third copy of

the same document.

282

JAKUB URBANIK

8 τέκτω2ν τῇ τέχνῃ, ὡ2ρ1µώµενος ἀπὸ ταύτης τῆς καλλιπόλε(ως)

Ἀντινοέων,

ἐκ δὲ θατέρου µέρους Αὐρήλιος Βίκτωρ υἱ̈ὸς Φιλήµµωνος, ἐκ µητρὸς

Μαρίας, καὶ αὐτὸς τῆς αὐτῆς τέχνης συνκείµενος, ἀπὸ ταύτης τῆς

Ἀντινοέων πόλεως, καταγόµενος ἀλλήλοις τὰ ὑποτεταγµένα,

12 χαίρειν. ὁµολογο2[ῦ]µεν κοινῇ γνώµῃ καὶ ἀδόλῳ προαιρέσει, συνεργάζεσθαι ἀλλήλοις εἰς {εἰς} τὴν ἡµῶν τῆς λεπτουργίας τεκτονικὴ?ν\

τέχνην, διὰ τ2αύτης ἡµῶν τῆς ἐγγράφου ὁµολογίας, ἄνευ παντὸς

δόλου καὶ φόβου καὶ βίας καὶ ἀπάτης καὶ ἀνάγκης καὶ πάσης συν16 αρπαγῆς τε καὶ περιγραφῆς κατὰ νόµους, ἑτοίµως ἔχειν ἡµεῖς

οἱ προγεγραµµένοι ἄνδρες τέκτονες, ἀπὸ τῆς σήµερον καὶ

προτεταγµένας ἡµέρας, ἥτις ἐστὶν τοῦ µηνὸς Χοιὰκ εἰκὰς

ἡµέρα τῆς παρούσης δευτέρας ἐπινεµήσεως, µέχρι περαιώσεως

20 ἑνὸς καὶ µόνου ἐνιαυσιαίου χρόνου, ψηφιζοµέ(νου) τοῦ αὐτοῦ χρόνο(υ)

ἀπὸ τῆς προειρηµένης ἡµέρας, ἐφ’ ᾧ ἡµᾶς, δίχα πάσης

ῥᾳδιουργίας, ἀµέµπτως καὶ ἀκαταγνώστως, συνοµονοεῖν

ἀλλήλοις καὶ συνκαµεῖν καὶ συνπνεεῖν εἰς πάντα τὰ ἁρµόττοντα2?α\

24 ἔργα τῇ ἡµῶν τέχνῃ, µετὰ πάσης ὑποταγῆς καὶ ὑπακοῆς

παρ’ ἀλλήλων εἰς ἀλλήλους ἐν ἅπασι καλοῖς καὶ ὀφελείµοις ἔργοις ?τε\

καὶ λόγοις ἀµέµπτως καὶ ἀκαταφρονήτως, δίχα πάσης

ῥᾳδιουργίας καὶ γογγισµοῦ καὶ ὑ2π2ερθέσεως καὶ ἀναβολῆς

28 ἔργων διόλου, εἰς πάντα τὰ ἐπιταττόµε2ν2α ἡµῖν ἢ καὶ προσταχθησόµενα παρ’ οἵου δήποτε ἀνθρώπο[υ] λόγῳ ἐργοχείρου

ἐπιταγῆ, ὥστε ἡµ2[ᾶ]ς πάντα ποιῆσαι καὶ ἐκτελέσαι µεθ’ ὑγιοῦς

τῆς πίστεως, καὶ ἀποκαταστῆσαι τοῖς ἰδίοις ἀβλαβῶς, καὶ τοὺς

32 µισθοὺς ¨ἱκανῶς [ἀ]π2ολαµβάνειν καὶ δι2αµερίσασθαι εἰς ἑαυτοὺς

τούτους κοινῇ ἐφ’ ἡµίσείας µερισµοῦ, δίχα πάσης κλοπῆς καὶ

ἀποστασίας: µὴ δυναµένου τινὸς ἡµῶν µήτε δυνησοµένο(υ)

ἀποστῆναι τῆς ἐµ2πιπ2τούση2[ς ἡ]µῖν ἐργ3[α]σ2ίας

36 καθ’ οἷον δήπο[τε χ]ρόνον ἢ καιρὸν ἢ ἡµέραν, καὶ ὑπερθέ[σ]θαι καὶ προφά2σ2ει2ς2 ἐπανατεῖναι καὶ τοῦ ἔργου καταφρονήσιν

κα2[ὶ εἰ] ἀποσταίνη τις παρὰ ταῦτα τὰ συντεταγµένα σύµφωνα ὑπερβῆ[ναι], καὶ µὴ δικ2[αί]ως ἐξακολουθῆσαι τῷ ἐπίοντι ἔργῳ καθ’

40 ἑκά2στην Θεοῦ βου2λ2οµένου, δίχα νοσήµ2α2τος, παρέξει τὸ παραβαῖ[ν]ον µέρος ὑ2πὲ2 [2 ρ ἀµ]ελείας χρυσοῦ [νοµ]ί1σµ(ατα) τέσσαρα. καὶ εἰ ἀπο-

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

283

σταί2η τοῦ ἔργου πρὸ συµπληρώσεως το[ῦ ἐ]νιαυτοῦ, τὸ αὐτὸ

πρόστιµον

ἐπιγινώσκειν δίχα κρίσεως καὶ δίκης καὶ οἵας δήποτε εὑρεσιλογίας

44 καὶ παραγραφῆς νόµ2ο[2 υ], ὑποκειµένων ἀ[λλή]λοις εἰς τοῦτο καὶ εἰς πάντα

τὰ προγεγραµµένα [π]άντ2ων ἡµῶν τῶν ἡµῖν ὄντων καὶ ἐσοµένων

πραγµάτων, κινη[τῶν τ]ε καὶ ἀκινήτων καὶ αὐτοκινήτων, ἐνεχύρου λόγῳ

καὶ ὑποθήκης δικαί[ῳ, εἰς] ἀποπλήρωσιν πάντων µέχρι τοῦ αὐτοῦ ἑνὸς

48 ἐνιαυτοῦ. καὶ ἐφ’ ἅπαντα τὰ προγεγραµµένα σύµφωνα ἐπερωτηθέντες

παρ’ ἀλλήλων καὶ ἀλλήλους ἐπερωτήσαντες καὶ εἰς πέρας ἄγειν

ὡµολ(ογήσαµεν) †

3. l. εἰκάδι | or Ἀντινό[ου π]όλει | l.ὁρµώµενος | or Ἀντι(νοέων) | 10. or συγκείµενος:

corr. from συνκειµενος | 11. l. καταγόµενοι | 13. or ?τῆς\ | 18. l. προτεταγµένης | 20.

corr. from ενιαυτιαιου | 23. l. συνπνεῖν | l. ἁρµόττοντα | 25. l. ὠφελίµοις | 27. l. γογγυσµοῦ | 30. l. ἐπιταγῆς | 37. l. καταφρονήσειν or καταφρονήσει?ν\ | 38. l. ἀποσταίη |

41. or ἀµελείας λόγο2[υ] | 43. l. εὑρησιλογίας | 48. or προειρηµένα

ll. 1–12: During the reign consulship of our most divine Lord Flavius Iustinus, the eternal Augustus Imperator, the fourth year, on the twentieth of

Choiak, in the second indiction year, in Antinoe, the most splendid.

Aurelios Danielis of father Iosephios and of mother Thekla, fine carpenter by trade, coming from the beautiful city of the Antinopolites, on one

side, and on the other side Aurelios Victor, son of Philemmon, of mother

Maria, of the same trade, belonging to the same city of the Antinoites

make and prepare for each other this mutually signed common and double agreement, upon the below revealed and concordant all conditions

which (it) contains. Greeting.

ll. 12–34: We agree with common will and non-fraudulent conviction to

work together for our trade of fine carpentry through this written agreement without any kind of fraud and fear and force and constraint and

deceit and all treachery and circumvention against the laws, that we, the

above-written artisans, are ready from today and the fixed date, which is

the twentieth day of the month Choiak of the present second indiction

(year), until the fulfilment of just one and single yearly time, the time

counted from the above-mentioned day, on which we, without any laziness, and being blameless and behaving in such a way that they would not

284

JAKUB URBANIK

be brought to the court come to one mind with one another and (decided)

to make joint efforts and breath together for all the corresponding works

of our trade with all subordination and compliance between one another

in all good and beneficial acts and words being blameless and behaving in

such a way that they would not be brought to the court and without any

laziness and indignation and entirely without delay and putting off the

works towards all commanded to us ordered by whichever man as an order

for manual labour, and to do and accomplish everything with sound trust

and to restore13 without any defect at our expense and to receive corresponding wages and to distribute by common consent to ourselves in halfshares, without any theft and (secretly) putting anything away.

ll. 34–37: And it is not allowed, and shall not be allowed, to neither of

us to withdraw from the work befalling on whatever time, period or day,

and to defer and to plead any excuses, and to disregard (our) labour.

ll. 38–44: And if anyone should withdraw from these conceded agreements and transgress (them), so it will happen that some work will result

(from this) to the party abiding the terms of the contract on a daily basis,

with an exception, with God so willing, of a disease (as a reason thereof),

the transgressing party shall pay because of this negligence, four coins of

gold. And if anyone should withdraw from the agreement before the year

is completed, he shall observe the same penalty without judicial proceedings and judgment and whatever tricky argumentation and circumvention

of the law.

ll. 44–49: And we are mortgaging to each other (in order to secure) all

this, and what is written above, all matters that belong and shall belong to

us: movable and immovable and self-movable by the by virtue of pledge

and right of hypothec, for the fulfillment of all (the agreements) until the

end of the same one year. And being mutually asked the formal question

about the above-written agreements, we have both stipulated and have

agreed to act (accordingly). †

The parties to the agreement, Aurelios Danielis son of Iosephios and

Aurelios Victor, son of Philemmon, both fine carpenters and originating

from Antinoopolis – just like in the preceding case – have established

their partnership for one year. Their undertake to work together, accept

orders from the clients and not to shrink away from the commanded

13

With Maspero, comm. ad h.l.: ‘faire des reparations’.

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

285

labours. It seems that any damage caused by their work should be personally amended by the partner responsible thereof (l. 31). The wages that

their singularly will collect should be divided in equal shares between

both associates. The parties also stipulate a penalty to be paid in case of

their negligent actions, in fact absence from work but for the case of illness, amounting to four solidi of gold. The partners additionally promise

to each other that they would not secretly keep for themselves anything

from the common labour – this clause has no parelel in the precedent

document where perhaps the ‘family’ context made it obsolete. Yet this

may have been a rather typical arrangement as among the Coptic ostraka

from Medinet Habu we find two sherds corresponding to one another

with oaths by which labour-partners assure each other not to have taken

money and trading goods from among common things.14

Just like the previous specimen also this one is concluded by a stipulatory clause and a general hypothec securing proper execution of the

contract.15

14

The editors, Elizabeth Stefanski and Miriam Lichtheim note that the sherds

match, and that the hand-writing on both belongs to the same person who must have executed them for illiterate promisees. O. Medinet Habu 89 (7th/8th cent.): I, Daniel, swear

(an) oath to | Mark, thus: By this place, by | its holy power, since | I have worked with you,

neither in | the north nor in the south have I | concealed from you the two | carats, | nor

in | the trading verso: goods. and O. Medinet Habu 90 (7th/8th cent.): I, Mark, swear (an)

oath, | thus to Daniel: By this place, | by its might, by its holy power, | since I have worked

| with you, neither I, | nor my wife, nor my | daughter, have ... verso: | whether | you were

in the north | or whether you were in the south, | I have not deceived | you in the trading

goods, | nor have my wife or | my daughter.

15

On this type of collateral, and especially its efficiency see my recent study ‘How to

make collaterals effective? A study of the late antique “real” securities’, § 2, with literature

therein cited (in print). One cannot but recall that the Byzantine legal practice virtually

equated conventional pledge (hypotheca) and possessory one (pignus – enechyron): our

papyrus is just yet another example proving this fact: see further ‘Tapia’s banquet hall and

Eulogios’ cell. Transfer of ownership as security for debt in Late Antiquity’ [in:], P. Du

Plessis (ed.), New Frontiers: Law and Society in the Roman World, Edinburgh 2013, pp. 151–

–174, at pp. 151–152 with notes.

286

JAKUB URBANIK

3. PARTNERSHIPS

IN THE ROMAN-BYZANTINE PAPYRI

I have already pointed out that our contracts are quite singular. Partnerships in general are rarely represented in the papyri. Many of the available

counterparts, dated to a later period, and thus comparable because of the

presumed influence of the Roman legal practice, are unions between

farmers who undertake to jointly cultivate estate leased by one of them,

sharing the duty to pay the rent (and so they cannot provide exact paralels).

And such is the case of P. Amh. ii 94 (= WChr. 347, Hermoupolis, 29

August 208), where a lessee of the public land undertakes to pay S of the

rent and taxes and his partner the remaining third share. The surplus is

to be divided in the same proportion. The associates will continue their

relation if the tenant should be obliged to continue the cultivation after

the expiry of the five-year period of the lease.16 Apart from a very generic

undertaking to jointly farm the land, no further duty of neither party and

their standard liability is specified.17 Another, and slightly earlier, contract from the Fayum closely follows the same pattern: in P. Oxf. 12 (Arsinoite nome, 153–154) a man, whose name has been lost, joins three colessees of a fishing right from two reservoirs of the village Karanis,

assuming a quarter share in their enterprise.18 The new partner accepts to

16

Cf. A. Ch. Johnson, An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome ii. Roman Egypt to the Reign of

Diocletian, Baltimore 1936, pp. 118–119, for a short commentary and translation. On a marginal note, one could recall that such a practice of the fisc and public officials was deemed

unjust (ἀδικία) already in the Edict of Tiberius Julius Alexander, of ad 68 (cf. OGIS 669,

ll. 10–15 and G. Chalon, ĽÉdit de Tiberius Julius Alexander. Étude historique et exégétique,

Lausanne 1964, pp. 101–108). Furthermore an imperial rescript by Hadrian to a judicial

inquiry deemed inhumane (valde inhumanus mos est iste: D. 49.14.3.6, Callistratus, 3 de iure

fisci; cf. further, Claudia Kreuzsaler & J. Urbanik; ‘Humanity and inhumanity of law.

The case of Dionysia’, JJurP 38 (2008), pp. 119–156 at 145). Obviously the steps against

abuse of the tenants were not really applied in practice as our papyrus shows.

17

See also, two slightly posterior, and almost more laconic in this respect, P. Lips. i 18

(Hermoupolis, 3rd/4th cent.), another ‘Teilpacht’ entered into by Aurelios Ausonios – the

owner of the cultivated land and Aurelioi Olympios and Paesis, and P. Oxy. x 1280

(Oxyrhynchos, 4th cent.), a partnership in lease of a camel-shed.

18

A similar agreement, of which details are lost, is to be found under P. Amh. ii 100

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

287

do all the work befalling his share and to pay one-fourth of the rent.

He will receive back the quarter of the surplus.19

From the later examples of such, the Dioskorean corpus brings one similar covenant. P. Lond. v 1705 (Aphrodite, 1st half of the 6th cent.), presents

an agreement between Besarion, uncle of our notary, and Viktor. They

agree to jointly cultivate a farm belonging to the Holy New Church, leased

earlier by Besarion, the duration is set to two years. It is indeed unfortunate that only the opening lines of the deed have been preserved, in fact we

may only find out that Besarion’s share was fixed at R. We do not know

how – if at all – a standard of care of the parties was agreed upon.

It is quite interesting to compare this document to another act involving Besarion, not an infrequent party20 to land leases in Aphrodite, especially of church estates, P. Lond. v 1694 (Aphrodite, 1st half of the 6th

cent.). In this document Dioskoros’ relative sub-leases21 a terrain belonging to the same Holy New Church to Aurelioi Mathias son of Ponnis and

Ibeis son of Apollos. The rent is to be paid in kind, both the lessees and

the lessor are to share the burdens to upkeep of a sakya and irrigation,

they also divide duties as to the provision of sowing seeds (Besarion is

responsible for the seeds of the main crop and his tenants for these of

(Ashmunen, 198–211): Hermes having obtained a lease of a lake for three years accepts

Kornelios alias Hermophilos as his partner in one-sixth share.

19

Other, still earlier, cases, bear similar features. In P. Mich. v 348 (Tebtynis, 27), again

a fourth partner is admitted into a partnership farming catoecic land, leased by one of

partners. A cheirographon, P. Flor. iii 370 (Hermoupolites, 4 December 132), documents

two Romans’ entering a partnership in equal shares to cultivate leased public land. Possibly similar content is to be expected in the poorly preserved P. Princ. ii 36 (?, 195–197) and still

unpublished P.CtYBR inv. 616 dated to the year 99, of which only the lower part survives: cf.,

<<http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/apis/item?mode=item&key=yale.apis.0006160000>>.

The fact that in the archive of the grapheion of Tebtynis there is only one entry on a partnership may show that the low number of papyri representing partnerships may not be entirely accidental. This enterprise was made by Orseus and others between 24 and 29 July 42

(P. Mich. ii 121 recto, col. viii, l. 12).

20

See also, e.g., P. Cairo. Masp. i 67107, which Maspero dated to 541, but may have been

executed earlier (cf. Introduction to P. Lond. v 1694, p. 95), by which Besarion leases land

from the priest Ioannes.

21

I am following the editor’s suggestion to correct τῇ ἁγίᾳ καινῇ | ἐκκλησίᾳ in lines 7/8

into genitive (see P. Lond. v, pp. 95–96).

288

JAKUB URBANIK

grass). Finally the produce of the field is to be divided into halves.22

Indeed this lease, functionally, is not far an agricultural partnership.

One more lease needs to be recalled here. SB iv 7369 (Hermopolis,

September 512) records an agreement to rent a vineyard by Apollos son of

Isidoros and Apollos son of Isaios from Flavius Taurinos, former soldier,

now a priest of the Main Church of Hermopolis.23 The land in question

consists of two parts: a fully productive one and of a half of parcel with

newly planted vegetation. The rent for the vineyard itself is fixed in kind,

the crop to be shared between the lessor, on one side, and the tenants and

their water supplier, on the other. The whole date-crop, instead, will belong to Apolloi upon payment of ´R gold solidus (cf. Frisk, introduction).

What is extremely interesting for our case is the way in which the tenants

undertake to take care of the land: for the cultivation of vines they will apply

all care and attention.24 They will secure the proper product of the vineyard

by working the vine according to the way it is usually done in the said plot

of land belonging to Taurinos.25 Dieter Nörr saw in these terms a fixing of

an objective standard of care, just like in the case of our carpenters.26

Obviously labour-partnerships would provide a far better comparison

to our cases. There are only three instances27 of such in the papyri. P. Köln

22

Ll. 18–19: κ1ατὰ τὸ ἥµισυ εἰς ἡµᾶς µὲν ὑπὲρ τῶν καµάτων | εἴς σε δὲ ὑπὲρ τῶν ἐκφορίων κτλ.

23

Flavius Taurinos ii is one of the personae of the multi-generational archive of Fl. Taurinos son of Plousammon and his descendants, on which, most recently, see Karolien

Geens, ‘Archive of Flavius Taurinos, son of Plousammon’ at <<http://www.trismegistos.org/

arch/archives/pdf/259.pdf>> (28.05.2004); original publication by H. Frisk, ‘Vier Papyri

aus der Berliner Sammlung’, Aegyptus 9 (1928), pp. 291–295: ‘Pachtvertrag über Rebenland’.

24

L. 11: πρὸς ἀµπελουργικὴν ἡµῶν ἐργασίαν καὶ πᾶσαν ἐπιµέλειαν καὶ φιλοκαλίαν, κτλ.

25

Ll. 21–22: ὥ2σ2τ2ε2 ἡ2µ2ᾶ2ς τὴν πᾶσαν ἀ2µπελ[ουργ]ικὴ[ν] ἐ2[ργα]σίαν ποιήσασθα[ι] ἀ[µ]έµπ[τ]ως κατὰ µίµησιν τοῦ µεγάλου σου | ἀµπελικοῦ χωρίου, κτλ. Cf. as well the Dioscorean P. Ham. i 21 (Antinoopolis, 4 September 569), ll. 22–29, yet without this ‘objective’ term

of comparison.

26

D. Nörr, Die Fahrlässigkeit im byzantinischen Vertragsrecht, München 1960, p. 191 and n. 3

See further J. L. Alonso, ‘Fault, strict liability and risk in the law of the papyri’, in this volume, pp. 19–108 at pp. 28–29.

27

I am not taking into consideration a curious Christian letter sent from from to Arsinoites, P. Amh. i 3a (= WChr. 126), in which Amelotti and Migliardi Zingale (infra, n. 30),

see an allusion to a non-profit partnership baking bread, as the context is too obscure to

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

289

ii 101 (Oxyrhynchos, 28 September 274 or 280)28 is a beginning of a contract of Aurelioi Sarapion and Silvanos forming an enterprise for the period of 18 months of some kind of work, perhaps to produce objects made

of tin.29 The only surviving clause foresees joint purchase of the objects

necessary for the undertaking.

The second, very particular, instance almost constituting a category of

its own, is given by two papyri from the Great Oasis, P. Genova 20 (25

June 319) and 21 (25 July 320).30 Aurelios Timotheos and Aurelios Uonsis

form twice a partnership designed to organise transport of men in and

out of the Great Oasis. Whereas the former partner should manage the

business, the latter associate provides the capital (12 talents in the earlier

case, 26 talents and 3000 drachms in the later). Both documents formulated as receipts of the manager for the money paid and his declaration to

that he would spend it to hire the porters.31

The last, securely identifiable,32 undertaking to joint-work is P. Lond. v

1794 (Hermopolis, 21 June 488). This, unfortunately badly damaged

papyrus – its whole lower part has been lost – documents a partnership

between two fruit sellers, Aurelioi Isidoros and Dorotheos. Because of its

state of preservation we cannot know with certainty what the exact condraw any reasonable conclusions. On this letter see M. Naldini, Il cristianesimo in Egitto.

Lettere private nei papyri dei secoli ii–iv, Firenze 1968, nº 6, pp. 79–85 with literature.

28

H. Harrauer, Paläographie, Textband, pp. 368–369, nº 178, opts for the year 280.

29

‘βρυτανική τέχνη’: see Bärbel Krämer & D. Hagedorn, P. Köln ii 101, comm. ad. l. 9;

and, more detailed, H. Hagedorn in the original publication: ZPE 13 (1974), pp. 127–129.

30

See the original edition and commentary of the editors: M. Amelotti & Livia

Migliardi Zingle, ‘Una società di trasporto nella Grande Oasi’, [in:] Studi di Storia Antica in memoria di L. De Regibus, Genova 1969, pp. 167–176 [= M. Amelotti, Scritti giuridici,

a cura di Livia Migliardi Zingle, Torino 1996, pp. 87–99] and D. C. Gofas, ‘Quelques

observations sur un papyrus contenant un contrat de société (PUG ii, appendice i)’, [in:]

Studi in onore A. Biscardi ii, Milano 1982, pp. 499–520.

31

P. Genova 20, l. 6 and 21, l. 8, assuming a very hypothetical reconstruction of the editors, cf. comm. ad h. ll.

32

Another deed of partnership from Hermopolis, P. Lond. v 1795 (datable to the 6th century), preserves only the penalty clause, stipulations and the subscriptions of the parties

and witnesses, one cannot therefore reconstruct what may have been the goal of this association.

290

JAKUB URBANIK

tract terms were, yet the whole act seems to be much simpler than cases

under examination. The parties undertake to share in equal parts the gains

and losses, nothing is said about the way in which they should execute their

tasks, or what their exact character would be. It seems that the division of

the profit would be conducted after the loss is covered and taxes paid.33

The final example comes from the Roman Dacia34 – and therefore cannot be used as a close comparison case to the Antinoopolitan carpenters

associations. Yet, it cannot be overlooked as it contains a very particular

formulation, perhaps the only direct reference to the standard of liability

adopted by the partners apart from P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158 and 67159 under

discussion here. The Transylvanian wax-tablets, CIL iii xiii (pp. 950–951 =

33

P. Lond. v 1794, ll. 12–16: ἐπ2ὶ1 κοινῷ λήµ|µ2ατι καὶ ἀναλώµ2[α]τ2ι καὶ ο2ὕ2τ2ω ἡµᾶς πα2ρ1α2σχεῖν

| [ο]ι1νῶς τα 2[ 2 2 2 ]2 2ια ἀν2α2λώµατα τῆς αὐτῆς τεχνῆ2 | κ2[αὶ] µ2ε2τ2ὰ τὴ[ν ἀπόδο(?)]σ2[ιν(?)] τῶν

φόρ[ω]ν καὶ τῶν ἀνα|λω2µάτων2 κτλ.

34

For a description and an overview of the literature, see most recently Meissel, Societas (cit. n. 9), pp. 171–174 and especially, Santucci, Il socio d’opera (cit. n. 9), pp. 206–209

with a particular analysis of the deceit-based liability assumed by the partners. The latter

author evokes as well in this instance (cf. n. 41 at the p. 207) a fragment of the second table

of Vipasca, the so-called lex metalli dicta, refering to division of the necessary expenses in

the mine by all the partners. A partner who would fradulently avoid contributing his

respective part of the costs, shall be deprived of the digging share corresponding to him.

Contrariwise, any expenses which would appear to have been made in good faith are to

be recovered from the other partners. The lex, thus, on one hand foresees a modification

on the standard terms on which a mining society would operate in the public mine, and,

on the other, additionally safeguards the good-faith nature of the contract of partnership.

2

See, FIRA I nº 104, now amended by S. Lazzarini, ‘Seconda tavola di Vipasca

(a. 117–138 d.C.’, [in:] G. Purpura (ed.), Revisione ed integrazione dei Fontes Iuris Romani

Anteiustiniani (Fira). Studi preparatori. i. Leges, Torino 2012, nº 2, pp. 43–62): col ii,

ll. 18–19: … Qui non ita contulerit, quive quid dolo | malo fecerit quominus conferat, quove

quem quosve ex sociis fallat, is eius putei partem ne | habeto, eaque pars socii sociorumve

qui inpensas fecerint esto. [Ei v]el ii<s> coloni<s> qui inpensam fecerint in eo puteo, in

quo plures socii fuerint, repetendi a sociis quod | bona fide erogatum esse apparuerit ius

esto. – ‘If anyone does not thus contribute or does anything with malice aforethought to

avoid contributing or to deceive one or more of his partners, he shall not have his share

of such diggings, and that share shall belong to the partner or partners who cover the

expenses. Alternatively, tenants who cover expenses in such diggings in which there are

many partners shall have a legal right to recover from their partners anything that is

shown to have been expended in good faith’. (transl. T. G. Parkin & A. J. Pomeroy,

Roman Social History. A Sourcebook, London – New York 2007, p. 283).

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

291

FIRA iii nº 157),35 document a societas (rei) danistariae. They were executed

on the 28 of March 167, yet the partnership in question had been created

earlier, on the 23rd of December 166 and was still to last for a fortnight

more (till the 12th of April of the same year). The parties, Cassius Frontinus and Iulius Alexander brought in, respectively, 267 and 500 denarii (the

former through agency of a slave Secundos, owed by Cassius Palumbus – as

we may imagine from the name, a co-freedman of Frontinus). The profit

35

Inter Cassium Frontinum et Iulium | Alexandrum societas dani[st]ariae ex | x Kal(endas)

Ianuarias q(uae) p(roximae) f(uerunt) Pudente e[t] Polione cos. in | prid[i]e idus Apriles

proximas venturas ita conve|n[i]t, _ut´ ut, quidq[ui]d in ea societati ab re | natum fuerit

lucrum damnumve acciderit, | aequis portionibus su2[scip]ere debebunt. | In qua societate

intuli[t Iuli]us Alexander nume|ratos sive in fructo (denarios) [qu]ingentos, et Secundus |

Cassi Palumbi servus a[ctor] intulit (denarios) ducentos | sexaginta septem pr[o Fron]tin[o

— —]s [—]chum e2i1s | [—]ssum Alburno [— —] d[ebeb]it. | In qua societ[ate] si quis d[olo

ma]lo fraudem fec[isse de]|prehensus fue[rit], in a[sse] uno (denarium) unum [— in] |

d[en]ar[ium] unum (denarios) xx [— —] alio inferre debe[bi]t, | et tempore perac[t]o

de[duc]to aere alieno sive | summam s(upra) s(criptam) s[ibi recipere sive], si quod superfuerit, | dividere d[ebebunt]. Id d(ari) f(ieri) p(raestari)que stipulatus est | Cassius Frontin[us,

spopon]dit Iul(ius) Alexander. | De qua re duo paria [ta]bularum signatae sunt. | [Item]

debentur Cossae (denarii) l, quos a socis s(upra)s(criptis) accipere debebit. | [Act(um)

Deusa]re v Kal. April(es) Vero iii et Quadrato co(n)s(ulibus). – ‘A partnership of moneylenders was made between Cassius Frontinus and Iulius Alexander from the 23rd of December 166 to the coming 12 of April in the following terms: that whatever shall be born in this

partnership or happen to gain or to loss they shall share it in equal parts. Iulius Alexander

has brought to this partnership five hundred denari, counted or in gain (following Arangio

Ruiz’s suggestion, p. 482, n. 1), and Secundus, the slave-representative of Cassius Palumbus

has brought two hundred sixty-seven for Frontinus [...…] he will owe (?). If anyone is found

to have committed fraud employing evil deceit in this partnership, he will owe to the other

for one as, one denarius, and for one denarius, 20 denarii. After this time, and having

deducted loans from the others, they shall divide either the above written sum or what shall

be left. Cassius Frontinus has asked a formal question that it shall be done, undertaken and

guaranteed, Iulius Alexander has promised. Of this thing two equal tablets have been

sealed. Similarly 50 denari are owed to Cossa, which he shall receive from the partners.

The deed was made on the 28th of March 167.’

For a detailed description of the deed, yet without further dogmatical considerations, see

V. Şotropa, Le droit romain en Dacie, Amsterdam 1989, pp. 220–223 and G. Ciulei,

Les triptyques de Transylvanie (Études juridiques), Amsterdam 1983, pp. 61–65, ch. v: ‘Notes sur le

contrat concernant une société. c.i.l., iii, p. 951’, as well as E. Pólay, ‘Ein Gesellschaftsvertrag

aus dem rö mischen Dakien’, Acta Ant. Acad. Scient. Hung., Budapest 1960, pp. 417–436 (non

vidi), and on the function of the stipulation in this instance, idem, ‘Die Rolle der Stipulation

in den Urkunden der siebenbürgischen Wachstafeln’, JJurP 15 (1965), pp. 185–220 at p. 218.

292

JAKUB URBANIK

was to be divided in equal shares. The parties enforced their agreement by

stipulations, expressively excluding any fraudulent conduct in their actions

and promising to pay ten-fold or twenty-fold penalty, for respectively damages lesser and greater in value than one denarius:

Pag. iii, ll. 3–4. In qua societ[ate] si quis d[olo ma]lo fraudem fec[isse

de]|prehensus fue[rit], in a[sse] uno (denarium) unum [— in] | d[en]ar[ium]

unum (denarios) xx [— —] alio inferre debe[bi]t ...

If anyone is found to have committed fraud employing evil deceit in this

partnership, he will owe to the other for one as, one denarius, and for one

denarius 20 denarii. …

What was the exact function of this clause? Obviously the parties did

not have to agree to provide fraud-based liability – exclusion of dolus as a

term of a contract would expressively contravene the principles of boni

mores, and hence would be void. Would we then have to read it as a limitation of their liability, excluding cases of any culpa, gross or lesser negligence?

4. THE STANDARD OF DILIGENCE

IN LABOUR-PARTNERSHIP AND THE CARE ASSUMED

BY THE ANTINOOPOLITAN CARPENTERS

An answer to this question depends on a solution adopted for much greater

dogmatic problem, which I cannot profoundly address in this paper, namely what the standard liability of a socius was.36 Part of the scholarship, especially older, assumes that it was limited to fraud.37 The newer approach sees

a gradual extension of the liability, imposed by the evolution of the social

and economic conditions.38 The good-faith principle governing the contract

36

See a very comprehensive overview in Santucci, Il socio d’opera (cit. n. 9), pp. 193–230.

37

To this directions goes, e.g., F. Schulz, Classical Roman Law, Oxford 1951, pp. 551–552,

who also points at irresolvable problems with the sources, professing at the end the ars

nesciendi in this instance.

38

Cf. Zimmerman, Law (cit. n. 9), pp. 461–465 with sources. This view might be corroborated by the fact that Lex Irnitiana reserves actio pro socio to the sole competence of

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

293

made grossly negligent conduct, especially one that a partner would have

abstained from in his own affairs, equal to fraud.39 There is only a tiny step

from this approach to adopting diligentia quam in suis as the model of liability.

And then finally the objective standard of care: as – so Zimmerman – Ulpian

in D. 17.2.52.2 seems to be going towards. The Justinianic attitude, however,

seems to have kept the former solution.40

<

As we have noticed none of the papyri documenting partnerships foresees a standard liability imposed on the parties. It is true that the material we possess – given its scarcity and quite unfortunate state of preservation – does not allow solid and irrefutable conclusions. Yet even with

all due diligence one may venture a statement that P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158

and 67159 are in this respect unique.41 How come then do we find such

covenants in these two – rather petty – agreements?

For Arthur Steinwenter these formulations simply express the will of the

parties: they decide to exceed the standard terms of the contract and instead

the provincial governor when quod dolo malo factum esse dicatur (Lex Irnitiana ixb, ll. 9–11).

The municipal magistrates would in turn try cases in which only culpa of a partner was

investigated and whereby a condemnation would not incur infamia. See, Francesca Lamberti, Tabulae Irnitanae. Municipalità e ius Romanorum, Napoli 1993, pp. 155–156 with lit.,

ibidem, pp. 348–349 for the text, and Santucci, Il socio d’opera (cit. n. 9), pp. 203–204.

39

Just as was the case in the contract of deposit in Celsian view: D. 16.3.32, with Zimmerman, Law (cit. n. 9), p. 463.

40

Cf. Just. Inst. 3.25.9 and D. 17.2.72 (Gai. 2 rer. cott.) with Zimmerman’s commentary,

Law (cit. n. 9), pp. 466–467 with nn. 96–99. On these passages cf. also Santucci, Il socio

d’opera (cit. n. 9), pp. 212–230. A profound examination of the Byzantine doctrine is to be

found in Nörr, Die Fahrlässigkeit (cit. n. 27), pp. 30–35.

41

W. Kunkel’s old hypothesis interpreting ἐπιµέλεια as the forerunner of the Byzantine

culpa, (‘Diligentia’, ZRG RA 45 [1925], pp. 266–351) must be refuted, see, now for all, Alonso,

‘Fault’ (cit. n. 26), pp. 26–36. One cannot agree with Kunkel’s view, who interpreted ἀµελέλια

in 67159 and the work-standard of the Antinopolitan craftsmen as hypostases of ἐπιµέλεια.

He was followed by F. Wieacker, ‘Haftungsformen des römischen Gesellschaftsrecht’, ZRG

RA 54 (1934), pp. 35–79, at pp. 75–76.: ‘In P. Masp. 67160 versprechen Handwerker einem

Akkordeur ἡµῶν τέχνη’ die Korrelativität zu ἀµέλεια zeigt, daß damit eine Diligenzpflicht

übernommen ist.’

294

JAKUB URBANIK

of assuming the duty to be as diligent as in their own matters they choose

the model of omnis culpa.42 Franz Wieacker, in turn, saw in these clauses a

way in which the notary exemplified the abstract terms of the fault liability.43

There seems to be, however, yet another explanation, even if rather

risky, dwelling not so much in the general ‘Schuldtheorie’ as in the personal style and educational background of the scribe. Reading the reference to the standard conduct of the Antinoopolitan artisans I could not

help but to recall well-known fragments of the Roman jurisprudential

texts which describe the liability of conductor operis.

D. 19.2.9.5 (Ulpianus libro 32 ad edictum): Celsus etiam imperitiam culpae

adnumerandam libro octavo digestorum scripsit: si quis vitulos pascendos

vel sarciendum quid poliendumve conduxit, culpam eum praestare debere

et quod imperitia peccavit, culpam esse: quippe ut artifex, inquit, conduxit.

Celsus wrote in the Eighth Book of his Digest that also imperitia (want of

skill) counts as negligence (culpa). If someone rents calves to be fed, or

accepts something for repair or polish, he must answer for his negligence, and

want of skill is negligence, because he receives the item as a (skilled) artisan.

D. 19.2.13.5 (Ulpianus libro 32 ad edictum). Si gemma includenda aut

insculpenda data sit eaque fracta sit, si quidem vitio materiae fractum sit,

non erit ex locato actio, si imperitia facientis, erit. Huic sententiae addendum est, nisi periculum quoque in se artifex receperat: tunc enim etsi vitio

materiae id evenit, erit ex locato actio.

If a precious stone has been given for the purpose of being set or engraved,

and it broke, if it was due to a defect in the material, there shall be no action

on hiring, but if it was due to lack of skill, there shall be action. This, it must

be added, unless the artisan assumed the risk: for then, even if it happened

due to a defect in the material, there shall be an action on hiring.

42

Steinwenter, ‘Gesellschaftsrecht’ (cit. n. 4), p. 502: ‘Wir sehen also, dass die Parteien

über die dem Recht der ‘societas’ übliche eingeschränke Sorgfaltsplicht hinausgehen und

Haftung für ‘culpa omnis’ vereinbaren.’

43

Wieacker, ‘Haftungsformen’ (cit. n. 37), p. 76: ‘Diese Versuche der Urkundenschreiber, ein konkretes Haftungsmaß zu finden, geben den Gedankengängen der vorjustinianischen Schuldtheorie ein deutlicheres Relief.’

DILIGENT CARPENTERS

295

D. 19.2.25.7 (Gaius ad edictum provinciale): Qui columnam transportandam

conduxit, si ea, dum tollitur aut portatur aut reponitur, fracta sit, ita id periculum praestat, si qua ipsius eorumque, quorum opera uteretur, culpa acciderit: culpa autem abest, si omnia facta sunt, quae diligentis-simus quisque

observaturus fuisset. Idem scilicet intellegemus et si dolia vel tignum transportandum aliquis conduxerit: idemque etiam ad ceteras res transferri potest.

If a column is broken when raised or carried or unloaded by someone who

took charge of it for transportation, he will be responsible for the damage,

whether this happened through his fault or through that of any of those

whose services he employs. There is no fault, however, if all precautions

are taken which a very diligent and careful man would take. The same of

course applies, we believe, if someone agrees to transport casks or lumber;

and the same also applies to all other things.

It is true that these texts concern a legal figure different from societas.

Yet I think they are perfectly applicable in our case: we have seen above

that in the legal practice leases of land for agricultural purposes come very

closely to agricultural partnerships. Moreover, the artisans forming a

labour-partnership will accept orders from their clients under the regime

of locatio-conductio operis, and while carrying them out they will have to

provide their clients with standard dilligence of a skilled artisan. It is,

therefore, quite reasonable to put these texts next to our contracts of partnership. In their description of the standard of liability Gaius and Ulpian

used the abstract notions of ‘want of skill’ – imperitia, ‘skilled artisan’ –

artifex, and finally the most diligent man – quae diligentissimus quisque observaturus fuisset. This is culpa in abstracto, the same one that the Antinoopolitan carpenters adopted, exceeding the statutory limits of liability in regular

partnerships in the times of Justinian.44 Further on, one could easily understand why they did so. In relations with their clients they would have to

provide the standard dilligence typical for a craftsman. Default of such

would constitute a breach of contract and consequently a loss, which would

eventually befall the formed partnership. No wonder then, the partners

were keen to secure this standard for their relationship, obliging themselves to keep it in all the external relations resulting from the partnership.

44

Cf. Nörr, Die Fahrlässigkeit (cit. n. 27), pp. 190–191.

296

JAKUB URBANIK

This particular formulation of P. Cairo Masp. ii 67158 is to be found

nowhere outside the Dioskorean corpus. It may be very well so, that the

phrasing of this papyrus as well as of P. Cairo Masp. ii 67159, also characterized by distinctly more legal flavour than any clause-formats in the earlier contracts of partnerships, bring forward reminiscences of Dioskoros’

legal education. It seems even more likely as the Digest cases I have just

cited seem to be perfect school examples, designed to a comprehensive

exposition of the particular standards of liability for the students. Should

that be the case – and by no means I am trying to exceed the limits of a

mere hypothesis – we would have yet another example of our notary’s

juristic skill.45 A question remains, as always in these instances, who were

the unqualified men who taught Dioskoros his trade, which at least in this

case proved to be perhaps not as spurious as Justinian deemed it to be.46

Jakub Urbanik

Chair of Roman Law and the Law of Antiquity

Institute of History of Law

Faculty of Law and Administration

University of Warsaw

Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28

00–927 Warsaw

Poland

e-mail: kuba@adm.uw.edu.pl

45

On this subject see, more recently P. van Minnen, ‘Dioscorus and the law’, [in:] A. A.

MacDonald, M. W. Twomey & G. J. Reinink (eds.), Learned Antiquity. Scholarship and Society

in the Near-East, the Greco-Roman World, and the Early Medieval West, Leuven – Paris – Dudley

MA 2003, pp. 115–133, and the conclusions of my studies: ‘Dioskoros and the law (on succession): lex Falcidia revisited’, [in:] Les archives de Dioscore d’Aphrodité cent ans après leur découverte.

Histoire et culture dans l’Égypte byzantine, éd. par J.-L. Fournet, Paris 2008, pp. 117–142 as well

as ‘P. Cairo Masp. i 67120 recto and the liability for latent defects in the late antique slave sales:

or back to epaphe’, JJurP 40 (2010), pp. 219–248; ‘Broken marriage promise and Justinian as a

lover of chastity. On P. Cairo Masp. i 67092 (553) and Novela 74’, JJurP 41 (2011), pp. 123–151.

46

Cf. Const. Omnem 7. … quia audivimus etiam in Alexandrina splendidissima civitate et

in Caesariensium et in aliis quosdam imperitos homines devagare et doctrinam discipulis

adulterinam tradere … – ‘as we have heard that even in the most splendid city of Alexandria and in that of Caesarea and in some others unqualified men deviate and pass spurious knowledge to the students’.