Toolkit for High-Quality Neonatal Services

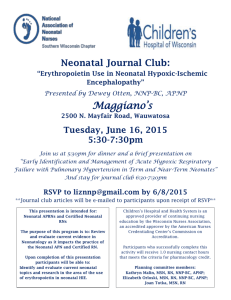

advertisement