Copland and Bernstein - St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

advertisement

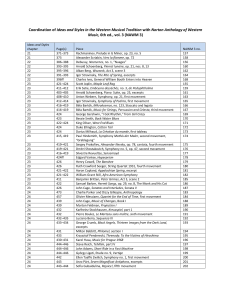

CONCERT PROGRAM March 23-24, 2013 David Robertson, conductor Mark Sparks, flute David Halen, violin COPLAND Quiet City (1939-40) (1900-1990) Cally Banham, English horn Thomas Drake, trumpet CHRISTOPHER ROUSE Flute Concerto (1993) (b. 1949) Amhrán— Alla Marcia— Elegia— Scherzo— Amhrán Mark Sparks, flute INTERMISSION BERNSTEIN Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium) (1954) (1918-1990) Phaedrus; Pausanias: Lento; Allegro marcato Aristophanes: Allegretto— Eryximachus: Presto Agathon: Adagio Socrates; Alcibiades: Molto tenuto; Allegro molto vivace David Halen, violin COPLAND Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo (1942) Buckaroo Holiday Corral Nocturne Saturday Night Waltz Hoe Down 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. Mark Sparks is the Helen E. Nash, M.D. Guest Artist. David Halen is the Sanford N. and Priscilla R. McDonnell Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, March 23, is the Joanne and Joel Iskiwitch Concert. The concert of Saturday, March 23, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. William C. Rusnack. The concert of Sunday, March 24, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Jo Ann Taylor Kindle. Pre-Concert Conversations are presented by Washington University Physicians. These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Series. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of Mosby Building Arts and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 FROM THE STAGE Mark Sparks on Christopher Rouse’s Flute Concerto: “It’s a work I seem to be returning to. It’s a piece that is written on a larger scale than flutists are used to playing. It offers a larger and wider range of possibilities. Perhaps more than any other concerto for flute, the solo instrument is given materials that are on a level of the great violin and piano concertos. It may be the most important concerto written for flute in the 20th century. “I’m fortunate in that I have a nice friendship with the composer. Having access to the composer is a really great thing. I can ask questions and get answers right from the person who wrote it. That’s awesome. “Chris places the soloist in an almost novelistic role. It’s a very dramatic piece and you change characters, you change points of view. You can go from elation to utter horror. Formally it’s cyclical, meaning you end up where you started. I think of it as beginning at a fair, and you go into the haunted house on a sunny day. You witness various things there. You go through different psychological states. You return to where you started, but maybe you notice this sunny day isn’t so sunny after all. “It’s also Chris’s most likeable and approachable work. He takes inspiration from British music, from dances and processionals. The most melodic music comes from Irish tradition, Irish song. He evokes those kinds of images—think of How Green Was My Valley.” Mark Sparks 25 AMERICAN MASTERS BY PA U L SC H I AVO TIMELINKS 1939-42 COPLAND Quiet City Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo World War II expands across the globe 1954 BERNSTEIN Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium) Army-McCarthy hearings help to bring down Sen. Joseph McCarthy and McCarthyism 1993 CHRISTOPHER ROUSE Flute Concerto Great Flood devastates the Midwest During the early years of the 20th century, the United States emerged as a dominant power on the world stage. Coincidentally or not, the same period saw the creation of the first American concert music of international importance, and throughout the last century our nation’s composers have solidified their standing as artists of the highest caliber. Whereas England, France, Germany, Russia, and many other nations have produced outstanding creative musicians during the past hundred years, no country has seen more lively or original musical activity than ours. Much of that activity has been in the fields of jazz and other styles of popular music, but those idioms have enriched the character and complexion of American concert works, which also have captured the world’s attention. Our concert presents American music from the last century. It features two revered composers—Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein—whose place in our nation’s cultural history is assured, as well as a younger man whose work attests to the continued vitality of our still relatively young musical tradition. 26 AARON COPLAND Quiet City FROM THEATER TO CONCERT MUSIC In the spring of 1939, Aaron Copland received a commission to write incidental music for a new play by the American dramatist Irwin Shaw. Entitled Quiet City, Shaw’s work imagined nocturnal scenes and the night thoughts of various characters in a modern urban setting. Copland was becoming quite accustomed to producing music on dramatic themes. Already he had demonstrated a theatrical flair with his highly successful ballets El Salón México and Billy the Kid. The same year, 1939, also saw the creation of film scores for The City and Of Mice and Men, as well as incidental music for another play, Five Kings, a Shakespearean potpourri starring and directed by Orson Welles. Copland produced the music for Shaw’s drama as requested, but the play was withdrawn after two trial performances. In the summer of 1940, the composer reworked the score’s main musical ideas into a piece for small orchestra, and in this form Quiet City was played for the first time in January 1941. The work is scored for a small ensemble of strings, English horn, and trumpet, the latter treated essentially as a solo instrument. (In the play, the main protagonist plays the trumpet, his music serving, as Copland stated, “to arouse the conscience of his fellow players and of the audience.”) The opening measures have the string choir and English horn outlining widely spaced chords, creating an impression of great stillness, and a three-note motif that proves the thematic germ for the entire piece. Soon the trumpet counters with nervous repeated notes and more rhapsodic phrases. The music slowly builds in intensity, at last reaching a stirring climax. From here it returns to its original mood and material, closing quietly and pensively. 27 Born November 14, 1900, Brooklyn, New York Died December 2, 1990, Tarrytown, New York First Performance January 28, 1941, at New York’s Town Hall, Daniel Saidenberg conducted the Saidenberg Little Symphony STL Symphony Premiere December 26, 1942, Vladimir Golschmann conducting Most Recent STL Symphony Performance December 12, 2008, David Robertson conducting Scoring English horn trumpet strings Peformance Time approximately 10 minutes CHRISTOPHER ROUSE Flute Concerto Born February 15, 1949, Baltimore, Maryland Now resides Baltimore First performance October 27, 1994, in Detroit, Carol Wincenc played the featured flute part with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Hans Vonk, who later became Music Director of the St. Louis Symphony, conducted STL Symphony Premiere April 8, 2005, Mark Sparks was soloist, with David Robertson conducting Most Recent STL Symphony Performance March 20, 2013, Sparks and Robertson combining again on the just completed California tour Scoring solo flute 3 flutes 2 oboes 2 clarinets 2 bassoons contrabassoon 4 horns 2 trumpets 3 trombones tuba harp timpani percussion strings Performance Time approximately 28 minutes A ROMANTIC AT HEART Christopher Rouse has achieved a remarkable dual success, writing music that is highly respected within his profession and deeply appreciated by concert audiences. Although he is well schooled in the modern techniques of his craft, communication has always been Rouse’s principal concern. Indeed, Rouse has said that compositional technique is always “less important than my need to express, which must mean that I’ve always been a Romantic at heart.” A neo-Romantic, perhaps, but by any description, the beauty and intense expressiveness of Rouse’s music has won acclaim from critics and music-lovers alike. In 1993 his Trombone Concerto received the Pulitzer Prize. Rouse now holds a faculty position at the Juilliard School and serves as composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Rouse composed his Flute Concerto in 1993 for the stellar flutist Carol Wincenc. The composer explains that the work was inspired largely by the rich musical tradition of the British Isles. “Although both of my parents’ families immigrated to America well before the Revolutionary War,” the composer observes in a preface to his concerto, “I nonetheless still feel a deep ancestral tug of recognition whenever I am exposed to arts and traditions of the British Isles, particularly those of Celtic origin.” He goes on to say that “the kinship I feel with this heritage— reflected in musical sources as distinct as Irish folk songs, Scottish bagpipe music and English coronation marches—never fails to summon forth from me a profoundly intense reaction of both recognition and homesickness.” SONG, DANCE, MARCH, ELEGY The concerto’s five movements form an arch design. At each end are very similar movements titled “Amhrán,” the Gaelic word for “song.” True to that meaning, these opening and closing portions of the composition have the solo instrument singing almost in the manner of an Irish folk song over eloquent, slow moving harmonies. 28 The heart of the concerto, in every sense, is the third movement. Rouse conceived it as a requiem for James Bulger, a child whose abduction and murder by a pair of 10-year-old English boys shocked all of Britain and the composer, who responded with this great elegiac outpouring. On each side of that centerpiece comes lively music: a march as the second portion of the work, and, as the fourth, a scherzo with rhythms suggesting a jig. Although clearly referring to traditional kinds of music, Rouse refracts the characteristic sound of his models through the prism of his own sensibility. LEONARD BERNSTEIN Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium) IN PRAISE OF LOVE Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade for solo violin with strings and percussion is widely regarded as the late composer and conductor’s finest concert piece. Bernstein wrote it, in 1954, after re-reading Plato’s Symposium, one of the Greek thinker’s famous philosophical dialogues. In that work, Plato recounts a conversation among a group of inquiring minds that has gathered over dinner in ancient Athens to consider the nature of love. Although the titles of the five movements that comprise Serenade clearly refer to the Symposium, Bernstein denied a literal correspondence between Plato’s work and his own. He admitted only that “the music, like the dialogue, is a series of related statements in praise of love, and generally follows the Platonic form through the succession of speakers at the banquet.” Each movement grows out of musical ideas presented in the previous one, and each is dominated by the solo violin. SOBER DIALOGUE, HEDONISTIC REVEL Bernstein identified Plato’s speakers in the headings of each movement. The opening presents Phaedrus, who begins the proceedings with a lyrical ode to Eros, and then Pausanias, whose description of the dualistic quality of love—earthly and celestial, physical and spiritual—is mirrored in a movement based on two contrasting themes. In the second 29 Born August 25, 1918, Lawrence, Massachusetts Died October 14, 1990, New York City First Performance September 12, 1954, in Venice, Isaac Stern was the featured violinist, the composer conducted STL Symphony Premiere February 20, 1982, Jacques Israelievitch was soloist, with Leonard Slatkin conducting Most Recent STL Symphony Performance May 6, 2007, James Ehnes was soloist, with Michael Christie conducting Scoring solo violin harp percussion strings Performance Time approximately 31 minutes First performance May 28, 1943, in Boston, Arthur Fiedler conducted the Boston Pops Orchestra STL Symphony Premiere August 18, 1973, the complete Four Dance Episodes was first conducted by Aaron Copland Most Recent STL Symphony Performance October 26, 2000, David Amado conducted a Kinder Konzert Scoring 3 flutes 2 piccolos 2 oboes English horn 2 clarinets bass clarinet 2 bassoons 4 horns 3 trumpets 3 trombones tuba timpani percussion harp piano celesta strings Performance Time approximately 18 minutes movement, the playwright Aristophanes invokes the mythology of love. Next comes the physician Eryximachus, who proposes bodily harmony as a model for lovers’ compatibilities. Bernstein described the music for this third movement as “an extremely short fugato scherzo, born of a blend of mystery and humor.” By contrast, the ensuing movement, inspired by Agathon’s speech praising love’s charms, is a simple aria in slow tempo. The finale begins with a weighty prologue, representing Socrates’s speech on the demonic power of love. This is interrupted, however, by the entrance of Alcibiades, who leads a band of drunken followers. They turn the gathering into a hedonistic revel that Plato seems to suggest is as true to the spirit of love as any of the sober discourses that have gone before. “If there is a hint of jazz in the celebration,” Bernstein wrote of this final part of his score, “I hope it will not be taken as anachronistic Greek party music, but rather the natural expression of a contemporary American composer imbued with the spirit of that timeless dinner party.” AARON COPLAND Four Dance Episodes from Rodeo A FRONTIER BALLET Aaron Copland is probably best known for three ballet scores he composed from 1938 to 1946. The first was Billy the Kid, the last the justly famous Appalachian Spring. The central portion of this ballet triptych originated in 1942 when Agnes de Mille, the American dancer and choreographer, asked Copland to write music for a new ballet set on a western ranch. Having already composed one cowboy ballet, Copland was reluctant to accept the assignment. But de Mille persuaded him by promising that her work would be unlike Billy the Kid: no legendary outlaws, no high drama, just a simple and universal story in a pastoral American setting. That story could hardly have been more elemental. A cowgirl raised at Burnt Ranch competes for the attention of the young ranch hands. Her search for romance culminates at a Saturday night barn dance, where she finally 30 gains a suitor. Rodeo, originally subtitled “The Courting at Burnt Ranch,” debuted in October 1942 and enjoyed an immediate success. The freshness of de Mille’s choreography certainly accounted for some of the work’s appeal, but Copland’s music was no less important. Among other things, Rodeo gave further evidence of the fertility of the composer’s use of American folk music, from which he also drew for his celebrated scores for Billy the Kid, Lincoln Portrait, Appalachian Spring, and other works. DANCE AND FOLK MUSIC Shortly after Rodeo opened, Copland adapted a concert suite of four dances from his ballet score. The first of these dances, “Buckaroo Holiday,” uses two authentic folk melodies: “If he be a Buckaroo by His Trade” (an old cowboy song that Copland introduces by way of a trombone solo); and “Sis Joe.” Rhythmic dislocations, sudden pauses, and unprepared shifts of harmony impart a comic touch to the music. After treating each tune separately, Copland combines them in complex counterpoint. The ensuing “Corral Nocturne” is a tender interlude in an asymmetrical 5/4 meter and marked by evocative woodwind solos. Copland stated that he wanted this music to convey the sense of loneliness felt by the ballet’s young heroine. “Saturday Night Waltz,” the third movement, hints at the sound of country fiddlers tuning up, as well as at the cowboy tune “Old Paint.” The final dance, “Hoe Down,” has long been the most popular portion of Rodeo. Here Copland quotes two squaredance tunes, “Bonypart” and “McLeod’s Reel,” using the sound of country fiddling to impart a lively rural atmosphere. Program notes © 2013 by Paul Schiavo 31 DAVID ROBERTSON Michael Tammaro BEOFOR MUSIC DIRECTOR AND CONDUCTOR David Robertson and the St. Louis Symphony just completed their California tour. David Robertson has established himself as one of today’s most sought-after American conductors, and has forged close relationships with major orchestras around the world through his exhilarating music-making and stimulating ideas. In fall 2012, Robertson launched his eighth season as Music Director of the 133-yearold St. Louis Symphony. In January 2014, while continuing as St. Louis Symphony music director, Robertson also will assume the post of Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Sydney Symphony in Australia. In September 2012, the St. Louis Symphony and Robertson embarked on a European tour, which included appearances at London’s BBC Proms, at the Berlin and Lucerne festivals, and culminated at Paris’s Salle Pleyel. In March 2013 Robertson and his orchestra returned to California for their second tour of the season, which included an intensive three-day residency at the University of California-Davis and performance at the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts, with violinist James Ehnes as soloist. The orchestra also performed at venues in Costa Mesa, Palm Desert, and Santa Barbara, with St. Louis Symphony Principal Flute, Mark Sparks, as soloist. In addition to his current position with the St. Louis Symphony, Robertson is a frequent guest conductor with major orchestras and opera houses around the world. During the 2012-13 season he appears with prestigious U.S. orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and San Francisco Symphony, as well as internationally with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic, and Ensemble Intercontemporain. Born in Santa Monica, California, David Robertson was educated at London’s Royal Academy of Music, where he studied horn and composition before turning to orchestral conducting. 32 MARK SPARKS HELEN E. NASH, M.D. GUEST ARTIST Mark Sparks was appointed Principal Flute of the St. Louis Symphony by the late Hans Vonk in 2000. He is a frequent soloist with the Symphony and other orchestras and has performed in the United States, Europe, Scandinavia, South America, and Asia. He has appeared as Guest Principal Flutist with many ensembles, including the New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, Detroit Symphony, and the Bergen (Norway) Philharmonic. In addition to these performances of the Rouse Concerto with the St. Louis Symphony, Sparks has recently performed the piece in Singapore and Taiwan, with plans underway for both the Chinese and Korean premieres. Prior to his appointment in St. Louis, Sparks was Associate Principal Flute with the Baltimore Symphony under David Zinman, and Principal Flute of the San Antonio Symphony and the Memphis Symphony. This summer Sparks returns to the Aspen Music Festival and School where he is an artistfaculty member and Principal Flute of the Aspen Chamber Symphony. He also will be teaching his fourth annual master class at Missouri’s Innsbrook Institute, and will join the faculty of the Pacific Music Festival in Sapporo, Japan. Sparks is an enthusiastic teacher and maintains a private studio in St. Louis. Sparks has recorded two solo albums, appearing on the Summit and AAM labels, and a new recording of French repertoire for flute and piano is planned for release in 2013. Born in 1960 and raised in Cleveland and St. Louis, Sparks graduated Pi Kappa Lambda from the Oberlin Conservatory as a student of Robert Willoughby, winning the 1982 Oberlin Concerto Prize. Prior to attending Oberlin, Sparks studied with former St. Louis Principal Flute Jacob Berg and trained in the St. Louis Symphony Youth Orchestra. Mark Sparks most recently performed as a soloist with the St. Louis Symphony in April 2012. 33 Mark Sparks will give the Chinese and Korean premieres of Rouse’s Flute Concerto. DAVID HALEN SANFORD N. AND PRISCILLA R. MCDONNELL GUEST ARTIST David Halen joined the faculty of the University of Michigan in the fall of 2012. David Halen is living a dream that began as a youth the first time he saw the St. Louis Symphony perform in Warrensburg, Missouri. Halen began playing the violin at the age of six, and earned his bachelor’s degree at the age of 19. In that same year, he won the Music Teachers National Association Competition and was granted a Fulbright scholarship for study at the Freiburg Hochschule für Musik in Germany, the youngest recipient ever to have been honored with this prestigious award. In addition, Halen holds a master’s degree from the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. Halen was named Concertmaster in September 1995, without audition, by the orchestra, and with the endorsement of then Music Directors Leonard Slatkin and Hans Vonk. During the summer he teaches and performs extensively, including his role as Concertmaster at the Aspen Music Festival and School. In 2007 he was appointed Distinguished Visiting Artist at Yale University, and at the new Robert McDuffie Center for Strings at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. In the fall of 2012, Halen joined the faculty of the University of Michigan, where he is Professor of Violin. As co-founder and artistic director of the Innsbrook Institute, Halen coordinates a weeklong festival, in June, of exciting musical performances and an enclave for aspiring artists. In August, he is artistic director of the Missouri River Festival of the Arts in Boonville, Missouri. His numerous accolades include the 2002 St. Louis Arts and Entertainment Award for Excellence, and honorary doctorates from Central Missouri State University and the University of Missouri-St. Louis. David Halen plays on a 1753 Giovanni Battista Guadagnini violin, made in Milan, Italy. He is married to Korean-born soprano Miran Cha Halen and has a 16-year-old son. He was most recently a soloist with the Symphony in February 2012. 34 A BRIEF EXPLANATION You don’t need to know what “andante” mean or what a glockenspiel is to enjoy a St. Louis Symphony concert, but it’s fun to know stuff. For example, what does it mean for composer Christopher Rouse to be “neo-Romantic,” as program notes author Paul Schiavo suggests? Neo-Romantic: Let’s look again at Rouse’s comment about compositional technique being “less important than my need to express….” To put this into context, compare Igor Stravinsky’s oft-quoted declaration “music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all.” Stravinksy, modernist, neo-classicist, puts a distance between himself and the Romantics. Think of all that is expressed, or that we perceive to be expressed by Beethoven, who kicks off the Romantic era. We don’t get that so much from Classicists such as Mozart, Haydn, or Stravinsky. They’re more about the purity of the composition, music as music. But the composers on this program, Copland, Bernstein, and Rouse, all are expressing ideas and moods and feelings in their music. They’ve gone back to Romantic inclinations, but without ignoring how music and life have changed. They are Romantics of their time, Romantics in an un-Romantic age. PRACTICING: DAVID HALEN, CONCERTMASTER “If I know the piece, I know the problem areas, so it’s my job to isolate the difficulties. Once isolated, I begin finding answers to the challenges that exist there. For example, determining what patterns of fingering will work best and most efficiently with the left hand while at the same time developing bowing that will be most convenient for the right hand. You practice to best perform these independent functions of your two hands. Think of patting your head and rubbing your stomach. It’s a little bit like that. “Every piece is like learning something new. Although with some individual composers, Beethoven for instance, you can find similar solutions in different pieces. One thing only years of experience will teach you is a method to find answers. You are able to re-visit problems on multiple occasions. Having a fresh mind is important, as is looking for inspiration. It’s music, after all, not a mathematical equation. You’re seeking a beauty that is unique.” David Halen 35 YOU TAKE IT FROM HERE If these concerts have inspired you to learn more, here are suggested source materials with which to continue your explorations. Aaron Copland and Vivian Perlis, Copland: 1900 through 1942 and Copland: Since 1943 St. Martin’s Press A lively, fascinating, and eminently readable autobiography by America’s iconic composer christopherrouse.com Christopher Rouse’s website offers a wealth of information about the composer’s music and activities Thomas Wolfe, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers Picador “Radical Chic” has become a classic of New Journalism, in which the white-suited scribe attends Leonard Bernstein’s athome fundraiser for the Black Panthers in 1970. What emerges is a satiric portrait of Bernstein and the times in which he lived. Read the program notes online at stlsymphony.org/planyourvisit/programnotes Keep up with the backstage life of the St. Louis Symphony, as chronicled by Symphony staffer Eddie Silva, via stlsymphony.org/blog The St. Louis Symphony is on 36 AUDIENCE INFORMATION BOX OFFICE HOURS POLICIES Monday-Saturday, 10am-6pm; Weekday and Saturday concert evenings through intermission; Sunday concert days 12:30pm through intermission. You may store your personal belongings in lockers located on the Orchestra and Grand Tier Levels at a cost of 25 cents. Infrared listening headsets are available at Customer Service. TO PURCHASE TICKETS Cameras and recording devices are distracting for the performers and audience members. Audio and video recording and photography are strictly prohibited during the concert. Patrons are welcome to take photos before the concert, during intermission, and after the concert. Box Office: 314-534-1700 Toll Free: 1-800-232-1880 Online: stlsymphony.org Fax: 314-286-4111 A service charge is added to all telephone and online orders. Please turn off all watch alarms, cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices before the start of the concert. SEASON TICKET EXCHANGE POLICIES If you can’t use your season tickets, simply exchange them for another Wells Fargo Advisors subscription concert up to one hour prior to your concert date. To exchange your tickets, please call the Box Office at 314-5341700 and be sure to have your tickets with you when calling. All those arriving after the start of the concert will be seated at the discretion of the House Manager. Age for admission to STL Symphony and Live at Powell Hall concerts vary, however, for most events the recommended age is five or older. All patrons, regardless of age, must have their own tickets and be seated for all concerts. All children must be seated with an adult. Admission to concerts is at the discretion of the House Manager. GROUP AND DISCOUNT TICKETS 314-286-4155 or 1-800-232-1880 Any group of 20 is eligible for a discount on tickets for select Orchestral, Holiday, or Live at Powell Hall concerts. Call for pricing. Outside food and drink are not permitted in Powell Hall. No food or drink is allowed inside the auditorium, except for select concerts. Special discount ticket programs are available for students, seniors, and police and public-safety employees. Visit stlsymphony.org for more information. Powell Hall is not responsible for the loss or theft of personal property. To inquire about lost items, call 314-286-4166. POWELL HALL RENTALS Select elegant Powell Hall for your next special occasion. Visit stlsymphony.org/rentals for more information. 37 POWELL HALL BALCONY LEVEL (TERRACE CIRCLE, GRAND CIRCLE) WHEELCHAIR LIFT BALCONY LEVEL (TERRACE CIRCLE, GRAND CIRCLE) WHEELCHAIR LIFT GRAND TIER LEVEL (DRESS CIRCLE, DRESS CIRCLE BOXES, GRAND TIER BOXES & LOGE) GRAND TIER LEVEL (DRESS CIRCLE, DRESS CIRCLE BOXES, GRAND TIER BOXES & LOGE) MET BAR TAXI PICK UP DELMAR MET BAR TAXI PICK UP DELMAR ORCHESTRA LEVEL (PARQUET, ORCHESTRA RIGHT & LEFT) BO BO UT UT IQ IQ UE ORCHESTRA LEVEL (PARQUET, ORCHESTRA RIGHT & LEFT) UE WIGHTMAN GRAND WIGHTMAN FOYER GRAND FOYER CUSTOMER SERVICE TICKET LOBBY TICKET LOBBY CUSTOMER SERVICE KEY KEY LOCKERS LOCKERS WOMEN’S RESTROOM BAR SERVICES BAR SERVICES HANDICAPPED-ACCESSIBLE WOMEN’S RESTROOM HANDICAPPED-ACCESSIBLE MEN’S RESTROOM MEN’S RESTROOM RESTROOM FAMILYFAMILY RESTROOM ELEVATOR ELEVATOR 38