The Age of Dissent Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thou Shouldst Be Living

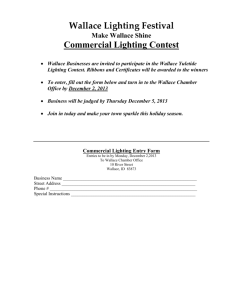

advertisement