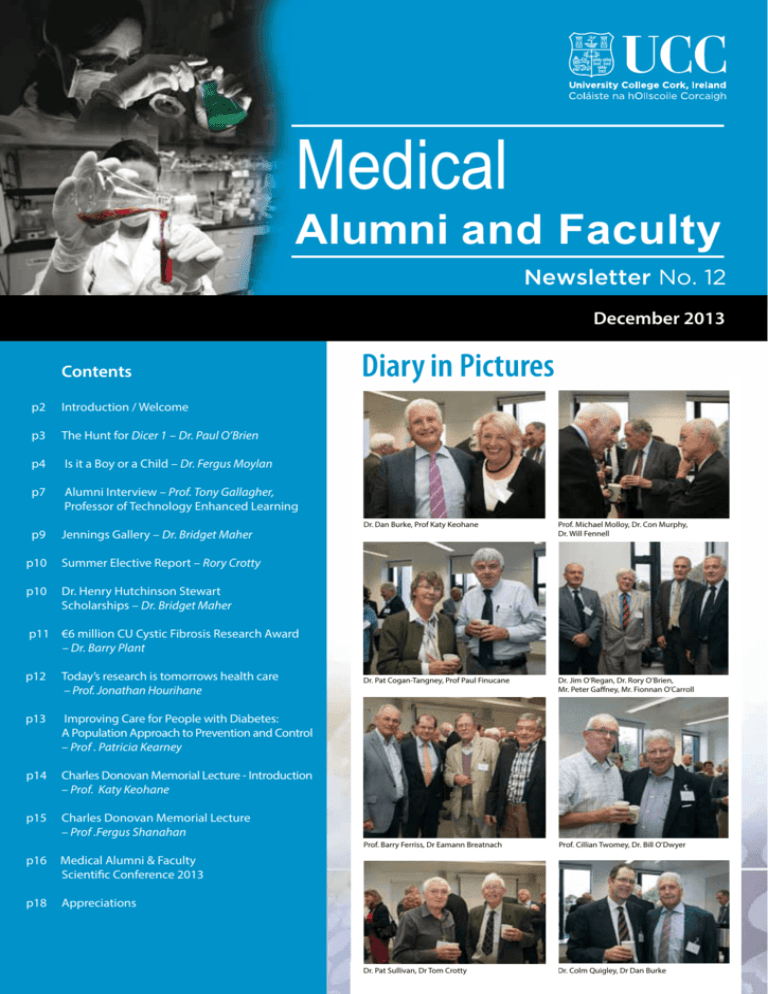

Medical Alumni Newsletter 2013

advertisement